Econo-missed #5: What is the real effect of the tipped minimum wage increase?

Economics as a discipline wields some ideological power through mystification. What is frequently referred to in media as “basic” economics is in fact loaded with ideological assumptions that often bear little resemblance to reality. Data for Progress (@DataProgress) is proud to host “econo-missed,” an economics advice column for the left, featuring a cast of young economics grad students and practitioners. This econo-missed comes Michael Paarlberg (@MPaarlberg) who is a professor of political science at Virginia Commonwealth University and an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC. He explores the impacted of a tipped minimum wage increase.

Earlier this month, the Washington, DC City Council overturned the results of a June referendum in which a majority of DC voters chose to raise the minimum wage for tipped workers in the city. The tipped minimum wage largely affects restaurant servers and bartenders, and is significantly lower than the minimum wage for all other workers: the federal tipped minimum wage is $2.13, compared to $7.25 for everyone else (in DC, it’s currently $3.89 vs. $13.25).

Lawmakers invalidating the democratic will of their constituents would be the kind of thing one would call unprecedented, were it not for the fact that, when it comes to the tipped minimum wage, it’s becoming a pattern. In Maine, voters also voted to raise the tipped minimum wage for servers, until restaurants successfully lobbied lawmakers to pass a bill to reverse it.

Perhaps more remarkable is the fact that lawmakers are repealing democratic votes based on faith alone. Though they dutifully repeat assertions made by the restaurant industry – some repeated by servers themselves – that bringing tipped workers up to parity with other workers would lead to mass restaurant closures and the end to tipping – they offer no evidence that this is true. “Save our tips” was the motto of the ballot measure’s opponents in DC, based the dubious premise that restaurant customers will suddenly start quizzing their servers about their hourly wages, and calculate proportionately how much of their tips to withhold.

There is, in fact, evidence of precisely the opposite: that when tipped workers get a raise, their total take-home pay – both wages and tips – goes up. At the same time, unemployment does not go up, nor do restaurant closings. This is what I found by analyzing data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for full service (i.e. tipped, not fast food) restaurant workers in New York and surrounding states, using a natural experimental technique of exploiting a policy change that happened in just one state and not in neighboring ones. By comparing economic variables of counties just on either side of the New York state border, one can more precisely estimate the impact of a policy change while controlling for other, unobserved factors.

New York is currently exploring a proposal to abolish the tipped minimum wage entirely, and bring servers up to par with other workers, as voters in DC and Maine tried to do. If it does so, it would not be the first: seven states – Alaska, California, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington – have a single statewide minimum wage which covers all workers, tipped or otherwise, all states where people have by all accounts not stopped going to restaurants or tipping their servers.

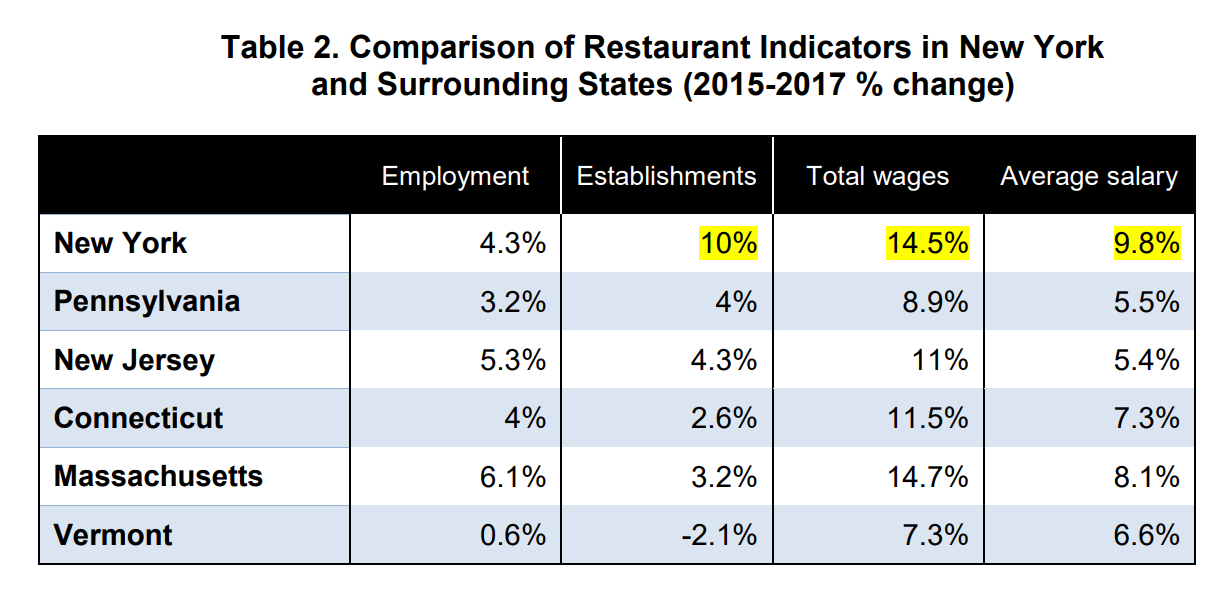

The best way to predict the likely outcome of such a move is by examining the last time New York raised its tipped minimum wage, from $5.00 to $7.50, at the end of 2015. Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, one can see that in the two years since the wage hike, restaurant workers at full service establishments in New York saw their average salaries go up nearly 10 percent, a larger increase than any other neighboring state. At the same time, employment in full service restaurants increased by 4 percent and the number of full service restaurants grew by 10 percent, a rate of growth that was higher than any neighboring state.

Statewide data tell an imperfect story, however. There are many variables that can affect whether a restaurant opens or closes or hires or fires servers, and at the state level, these unobserved factors are too many to draw causal conclusions.

To isolate the effect of the tipped minimum wage, it is necessary to use econometric techniques designed to control for these unobserved factors. This research employs a quasi-experimental design approach based on the difference-in-differences (DiD) model that is the cornerstone of most minimum wage studies, beginning with David Card and Alan Krueger’s 1993 study of the effect of the minimum wage increase in New Jersey vs. Pennsylvania, which did not see a minimum wage increase. Card and Krueger’s 1993 NBER paper found no negative impact on employment from New Jersey’s minimum wage hike, contradicting economic orthodoxy and popularizing the DiD method, as well as regression discontinuity design (RDD), for subsequent minimum wage studies.

This study compares changes in employment, establishments, and worker pay for full service restaurants in counties just on the New York side of the border to those in counties just across the border in neighboring states, which did not pass a new tipped minimum wage increase in the same period. The logic of DiD is that border counties share the same geography, demographics, and labor markets, and are thus much more comparable than New York as a whole is to Pennsylvania as a whole.

First, comparing New York border counties to all other neighboring state border counties, one can see restaurants on the New York side saw increases in restaurant employment and establishments, and significant increases in servers’ salaries and total wages – which include both base wages and tips – all at a greater level than border counties in neighboring states.

Secondly, limiting the comparison to just the New York-Pennsylvania border – the longest border New York shares with a neighboring state – one can see a similar story. In the two years after the tipped minimum wage increase, restaurants on the New York side of the border fared much better employment and salaries, and had nearly exactly the same rate of establishment growth as restaurants on the Pennsylvania side of the border. Servers made more money, and restaurants did not close down or lay off servers: employment went up 1.2 percent, there were 1.9 percent more restaurant openings, and servers got a nearly 13 percent boost in their wages, compared to servers on the Pennsylvania side who saw less than half the rate of wage growth and a quarter the rate of job growth.

There is, in short, no evidence of the dire predictions of a collapse of the restaurant industry, mass layoffs of servers, or precipitous drops in take home pay due to customers withholding tips. Quite the opposite happened in New York the last time it raised its tipped minimum: workers earned significantly more and saw more job and establishment growth compared to their peers in neighboring states and counties. The two tiered minimum wage is an aristocratic era anachronism designed to create a permanent servant class, and shift responsibility for servers’ livelihoods from employers onto customers. Just as we have failed to see an abandonment of restaurants in California or the six other states which did away with it, we’re unlikely to see such a scenario in states that follow suit. Lawmakers might review some evidence before they overturn any more votes based on a chicken little story.

Michael Paarlberg (@MPaarlberg) is a professor of political science at Virginia Commonwealth University and an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC.