Long Term Care for all is a Political Winner

By James Medlock (@jdcmedlock) and Colin McAuliffe (@ColinJMcAuliffe)

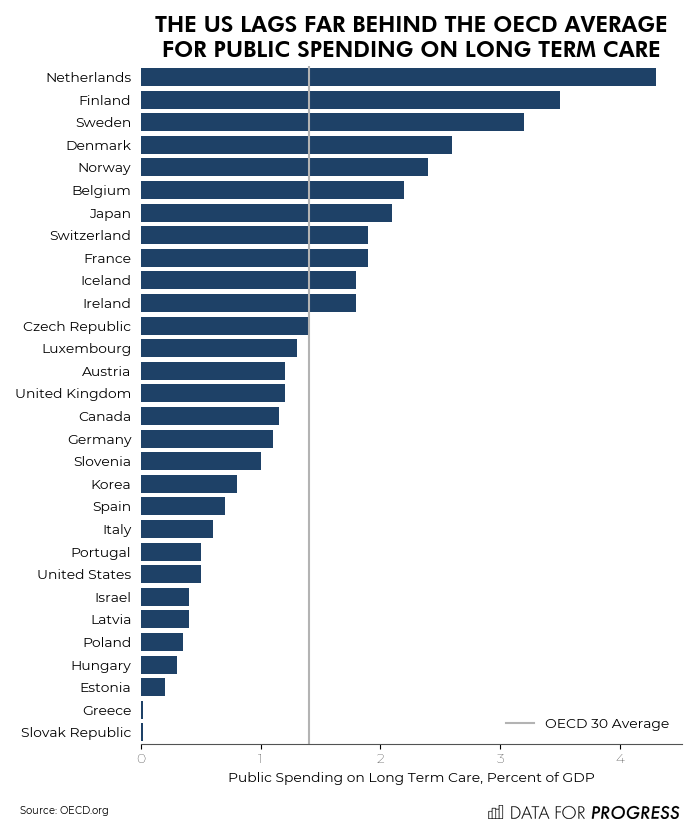

America is facing a long-term care crisis. As our population ages, an increasing share of Americans need support with basic activities of daily life, like dressing, eating, and using the bathroom, due to old age, chronic illness, or a disability. A person turning 65 today has a 70% chance of needing at least some long-term support during the remainder of their lives. But unlike the rest of the rich world, the US lacks a universal social insurance system for people who need long-term care. A universal long-term care program is popular with the American public and would help ensure disabled and elderly people are able to lead dignified lives.

Here at Data for Progress, we have several principles of coverage:

Emphasis on allowing people to stay in homes and communities. Prioritize allowing people to stay in their homes and communities if they so desire.

Mandatory and universal. Follow the logic of social insurance, where everyone pays into the same risk pool and everyone receives benefits when they need them.

Cash-based reimbursement. Providing benefits in cash rather than in-kind allows programs to be self-directed, giving people more autonomy to determine how they’d like to receive care, and allowing friends and family to be reimbursed for the care they provide. Informal caregivers should receive training and support.

Pay workers living wages. Workers for agency-based home care and institutional care should be paid living wages, which has been shown to dramatically increase the quality of care (and even save lives).

The Status Quo

The private long-term care (LTC) insurance market is in a state of market failure. The number of insurers offering LTC insurance has plunged 90% since 2000 and private insurers only account for 8% of total LTC spending. The policies that remain on the market have premiums that are unaffordable for those who aren’t wealthy (one in four millionaires has LTC insurance, compared to only 1 in 25 people with wealth between $50k-$100k). And even those with LTC insurance may not be fully protected, as policies tend to be time-limited and not guaranteed to cover all care needs.

Many seniors assume they can rely on Medicare. But with a few exceptions, it doesn’t cover long-term care. Instead, Medicaid finances a majority of the long-term care services in the US. To be eligible, recipients must have no more than $2,000 in countable assets and no more than $2,313 in monthly income. This strict asset and means-testing forces people to impoverish themselves to gain eligibility, and often results in ”Medicaid divorces” to protect spouses’ assets. For those able to qualify, the quality and availability of LTC services vary state-by-state. Many states have waiting lists for their home care programs due to fiscal constraints and worker shortages have also become common in recent years. Despite these issues, Medicaid is a lifeline for millions of people. In the landmark Olmstead decision in 1999, the Supreme Court mandated that people with disabilities must be allowed to stay in their communities rather than be forced into isolated institutions. As a result, state Medicaid programs have shifted towards Home and Community Based Services (HCBS), which now make up a majority of Medicaid long-term care spending. Not only has this enabled people to live more socially integrated lives and “age in place” in accordance with clinical best practices, it has also saved money in the long run. While many HCBS programs are limited to agency-provided in-home care, some states offer Medicaid Cash and Counseling programs that provide recipients with a budget they are free to allocate to either professional or informal caregivers (such as friends and family). Outcomes on this type of program (also known as self-directed or consumer-directed care) have shown incredible results. One study showed that patients receiving paid care from family members (rather than professional home care) were 30% less likely to have bedsores, 50% less likely to go to the emergency room, and reduced Medicaid spending by $1,370 over 9 months. Another study confirmed that patients had greater satisfaction with their care and had fewer unmet needs compared to traditional Medicaid HCBS recipients. And even workers have been found to be more satisfied with conditions and pay in Cash and Counseling programs.

While Medicaid has been a bright spot, the heavily means-tested nature of the program has prevented many people from accessing it until they drain their assets. By 2029, a majority of middle income seniors (14.4 million people) will end up in a situation where they are not eligible for Medicaid, but also unable to afford the cost of private care. People stuck in this gap generally rely on unpaid family care. In 2013, family caregivers provided a total of $470 billion worth of unpaid care. Caregivers face foregone wages, reduced future social security benefits, and spend an average of $7,000 on care related costs annually. The work family caregivers do plays an important role and should be valued more highly. Unfortunately most of the support for family caregivers is provided through a patchwork of complicated provisions in the tax code, including the Dependent Exemption, Dependent Care Credit, Dependent Care Flexible Spending Accounts, and the Caregiver Medical Expense Deduction. These provisions have gaps that exclude many caregivers, especially the poorest, and they place a tremendous bureaucratic burden on people who already have their hands full.

The CLASS Act and LTC Commission

The future of long-term care has been a looming problem for a long time. Wilbur Cohen, one of the key architects of Medicare and Social Security, told the Senate Special Committee on Aging in 1985 that “the most urgent program development would be to figure out some way … to include long-term care.” This warning went largely unheeded, until the Affordable Care Act, which contained a provision called the CLASS Act meant to address the long-term care crisis. It was a modest public option for long-term care insurance, which would provide a $50/day benefit for those who had opted into the program and paid premiums. But as the program was being set up, it became clear that setting premiums high enough to make the program solvent would be too high to attract a sufficiently healthy risk pool. In other words, the problem of adverse selection would undermine the program just as it had in the private market. Recognizing that it would be unworkable, the Obama administration scrapped the program before implementation.

In light of the failure of the CLASS Act, Congress established the Long-term Care Commission to study the problem. The commission failed to come to a consensus on financing and so some members of the commission released an alternative report. This report concluded that “to spread the risk for the costs of long-term services and supports as broadly as possible, provide benefits to people of all ages who need them, and allow individuals and families to meet their responsibilities, a public social insurance program that is easily understood and navigated must be established.”

Current Proposals

While the specific issue of long-term care hasn’t gotten a lot of attention on the campaign trail, there is a stark divide among the candidates on this issue. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have endorsed universal long-term care as part of Medicare for All. The bill initially lacked long term care benefits, but after activist pressure it was added to the most recent version. The details have yet to be fully fleshed out, but the bill commits to providing universal home and community-based supports. Frank Pallone also has a discussion draft of a standalone bill that would add a long-term care benefit to Medicare. While improvements could be made, it’s an encouraging development.

Joe Biden, on the other hand, touts his support for a new tax credit for family caregivers on his campaign website. The tax credit he endorses, first formulated by Third Way, explicitly excludes those with earnings below $7,000, so the 40% of family caregivers who provide care full time would not receive any benefit. And it would add yet another bureaucratic burden in addition to the four existing benefits in the tax code. While hiding it in the tax code and excluding the people that need it the most may be enough to attract a few GOP co-sponsors, it’s not enough to actually address the problem.

Expanding public healthcare benefits can present a number of different political challenges, especially when it comes to financing them. Means testing and cost sharing are often floated as a way to reduce the sticker price (and hence the required tax) for funding new programs. But when it comes to LTC, there’s no reason to triangulate. In a poll conducted by Tufts University and Data for Progress, respondents were asked to consider universal long term care fully financed by the federal government through a new payroll tax. Programs for LTC for people over 65 as well as LTC for people with disabilities who are younger than 65 were both tested. Despite hearing Republican counter arguments about funding through broad-based tax increases (which are typically unpopular), support for LTC for both seniors and people with disabilities is incredibly strong. Comprehensive long term care benefits for seniors and people with disabilities garner net support of 33 percent and 30 percent respectively.

These results are in line with some of our past findings, where broad based tax increases can be politically viable funding mechanisms for progressive policies, provided that the size of the tax is small and the program it funds is very popular.

From a policy perspective, there’s no justification for means testing long term care, which clearly should be universal benefit. There’s also no justification for political triangulations when support for these policies is so high. In fact, full throated support of LTC may give Democrats a pathway to winning older voters. Politics has become increasingly polarized by age with Republicans becoming more and more reliant on winning older voters by large margins. This is likely to create some tension, since Republican elites are dedicated to destroying the US welfare state, whose primary beneficiaries are the elderly voters that Republicans need to win.

Support for long term care for seniors is higher among the elderly than it is among younger voters, the reverse of the typical trend for progressive policies. Aside from being popular among the broader public, the popularity of long term care among seniors disrupts a crucial coalition that Republicans need to win elections.

As the president of AARP reminds us, the boomers have all the money, and it’s true that they own a disproportionate share of wealth. However, that wealth is concentrated in the hands of a relatively small group of people, while many elderly folks are forced to endure levels of economic precarity and indignity that are nothing short of tragic. A platform of Social Security expansion, aggressive solutions for lowering pharma costs, and long term care would be a major step forward in providing for our nation’s elders, and would help Democrats win elections as well.

Full Question Wording

LTC for Seniors

Some Democrats have proposed spending $120 billion per year to provide seniors with comprehensive long term care benefits through Medicare. Long term care benefits would cover nursing home care, in-home care, and assistance with daily activities such as eating, bathing, and housework. The expansion in coverage would be funded with a 1.5% payroll tax on all workers.

Democrats say that seniors are unable to afford long term care services that are not covered by Medicare, and that expanding benefits would improve quality of life for many seniors.

Republicans say that American workers are already taxed too much and that increasing government spending is irresponsible.

Would you support or oppose this proposal?

LTC for People with Disabilities

Some Democrats have proposed spending $80 billion per year to provide people with disabilities with comprehensive long term care benefits through Medicare. Long term care benefits would cover nursing home care, in-home care, and assistance with daily activities such as eating, bathing, and housework. The expansion in coverage would be funded with a 1% payroll tax on all workers.

Democrats say that many people with disabilities are unable to afford long term care services, and that providing long term care benefits would improve their quality of life.

Republicans say that American workers are already taxed too much and that increasing government spending is irresponsible.

Would you support or oppose this proposal?

James Medlock (@jdcmedlock) is a Bay Area-based healthcare policy analyst.

Colin McAuliffe (@ColinJMcAuliffe) is a co-founder of Data for Progress.