Identifying the Working Class

By Kevin Reuning (@KevinReuning)

“Working Class” remains a contentious term in popular discourse. As I discussed in a previous blog, this term is embedded with assumptions not only about socioeconomic status but race and occupation. We recently fielded a survey with YouGov Blue in order to get more precise handle on what it means to be “working class” and how those who fit this description vote.

To start, we asked 1,282 voters to write, in their opinion, what “it means to be working class in America today”. Below shows the top words, bigrams (two words together) and trigrams (three words together) after stemming the responses. This shows the words that were commonly used across all survey respondents. What we see are words generally associated with work near the top (work, job, and paycheck) for example. This is not surprising, as working class starts with some initial idea of working for a living opposed to living off of inheritance or investments. We also see a lot of reference towards economic instability or poverty. This is apparent in words and phrases like “live paycheck to paycheck” or poor.

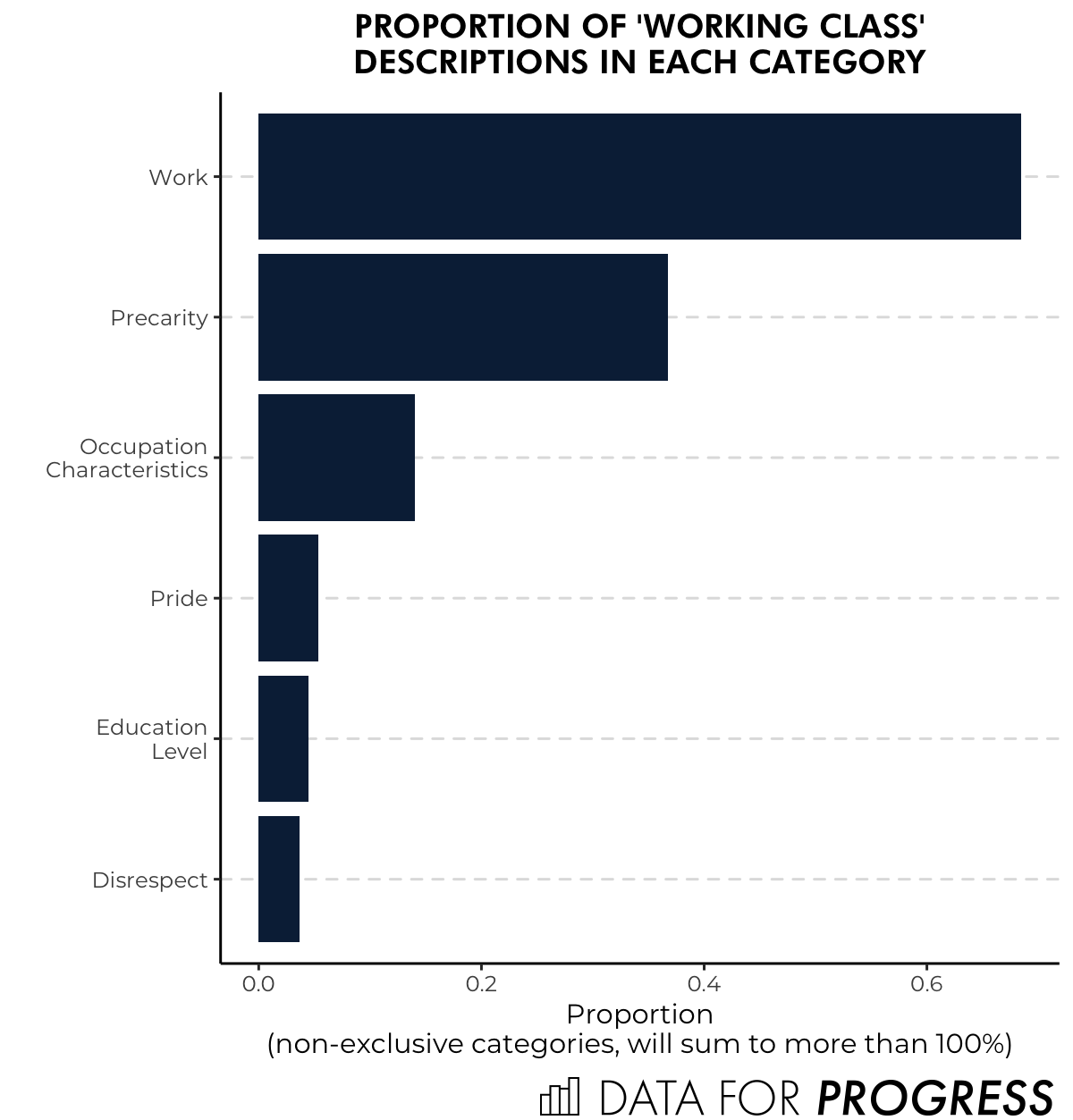

This initial examination of popular words and initial reading of some responses led to a simple coding scheme that I used to organize the responses. I created six non-mutually exclusive categories and coded each response for if they fit into one or several of them:

Work: This was any response that indicated those in the working class were defined by the fact that they work. This includes responses that mentioned other necessary characteristics, as long as working was one of them.

Precarity: Responses that indicated either poverty or other forms of economic insecurity. This would include responses that used the phrase “living paycheck to paycheck”

Occupation Characteristics: Some indicated particular types of jobs fit into working class. Often, but not always, this took the form of blue-collar jobs. This category captured those types of responses.

Education Level: Here I coded for responses that included language about particular educational attainment. This usually was a responses that defined the working class as not having a college degree.

Pride: Some respondents, rather than discussing the characteristics that would put someone in the working class, instead discussed how the working class was important -- describing them as the ‘“backbone” of America, for example.

Disrespect: On the other side of the coin, some respondents discussed how the working class were ignored or disrespected. This included both responses that indicated that the rich didn’t care about the working class, as well as responses that referenced politicians ignoring or “screwing over” the working class.

The proportion of responses that fit into each category are below. Work in general was referenced by 68% of respondents while 37% indicated some extent of poverty or economic precarity as a defining trait of working class. Many of the mentions of work in general included other aspects as well. Roughly 22% of respondents defined working class as only being defined by working and nothing else. The other categories were significantly smaller with 14% describing some sort of occupation characteristic and the remaining categories were referenced less than 10% of the time each.

The descriptions of working class indicate two relatively common definitions. The first is an expansive definition that includes anyone who has to work as being a member of the working class. This excludes those whose income predominantly comes from investments -- a trait that is mainly true for only the very top economic classes. The second is a narrower definition that focuses on a class of individuals who are in a precarious economic position. Although income and education might be an important determinant of experiencing this type of precarity, they are not perfect indicators. As one respondent said: “I don't even know anymore. I have a masters degree with two jobs, and I'm broke.”

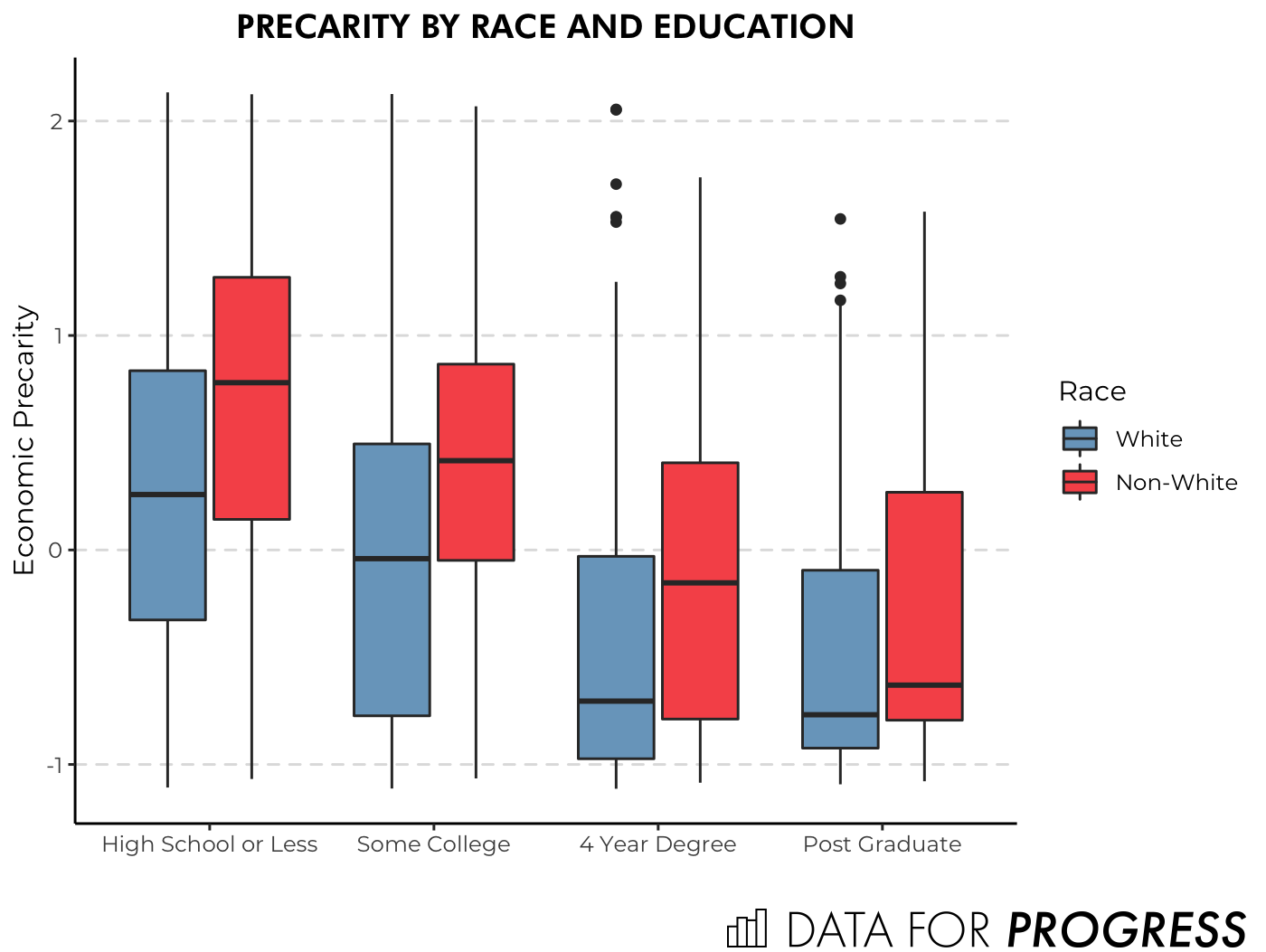

With this definition of working class in hand, we can explore the political preferences of this group. To do this I constructed a latent scale of precarity using eight Yes/No questions that identified if individuals have access to credit, emergency money, and other financial instruments (full list of questions below). Using Item Response Theory I created a latent measure where negative numbers indicate less economic precarity and higher numbers more economic precarity. The distribution of economic precarity is below and is not close to normal. There is a group that is very economically sound, and then a long tail to the right of individuals facing different degrees of economic precarity.

Examining the levels of economic precarity across race and education we see an expected pattern: higher education leads to less economic precarity, but there is a clear racial gap. Whites without a high school degree are roughly at the same level of economic precarity as non-whites with a 4-year degree.

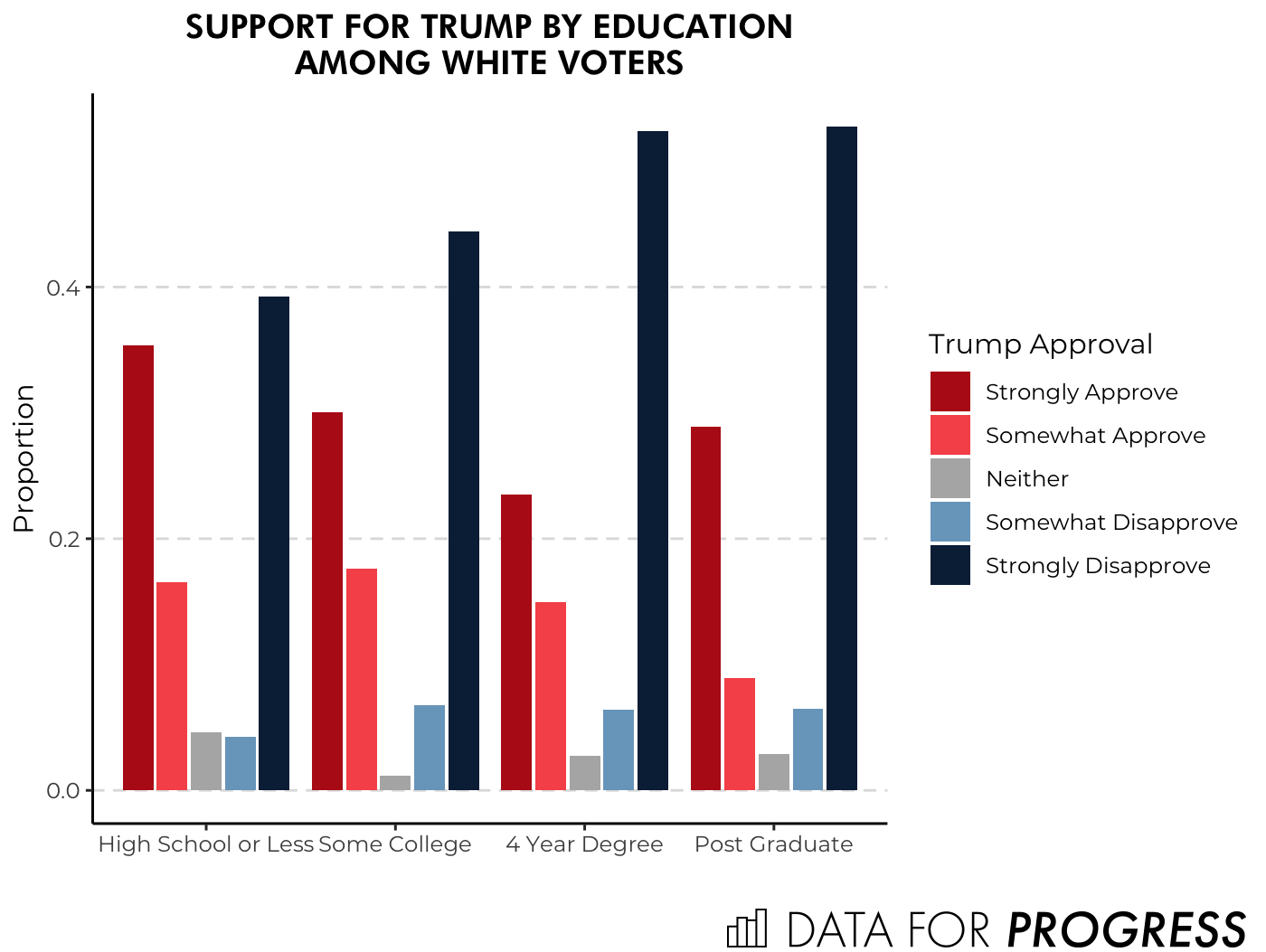

Turning to preferences towards Trump, we discover something very interesting that cuts against common narratives. Donald Trump’s base has often been described as the “white working class.” This is often defined as those who are white and who do not have a college degree. The data we have does demonstrate this. There is a clear trajectory where lower educational attainment leads to higher support for Donald Trump. This is somewhat true in the population at large but especially true among white voters:

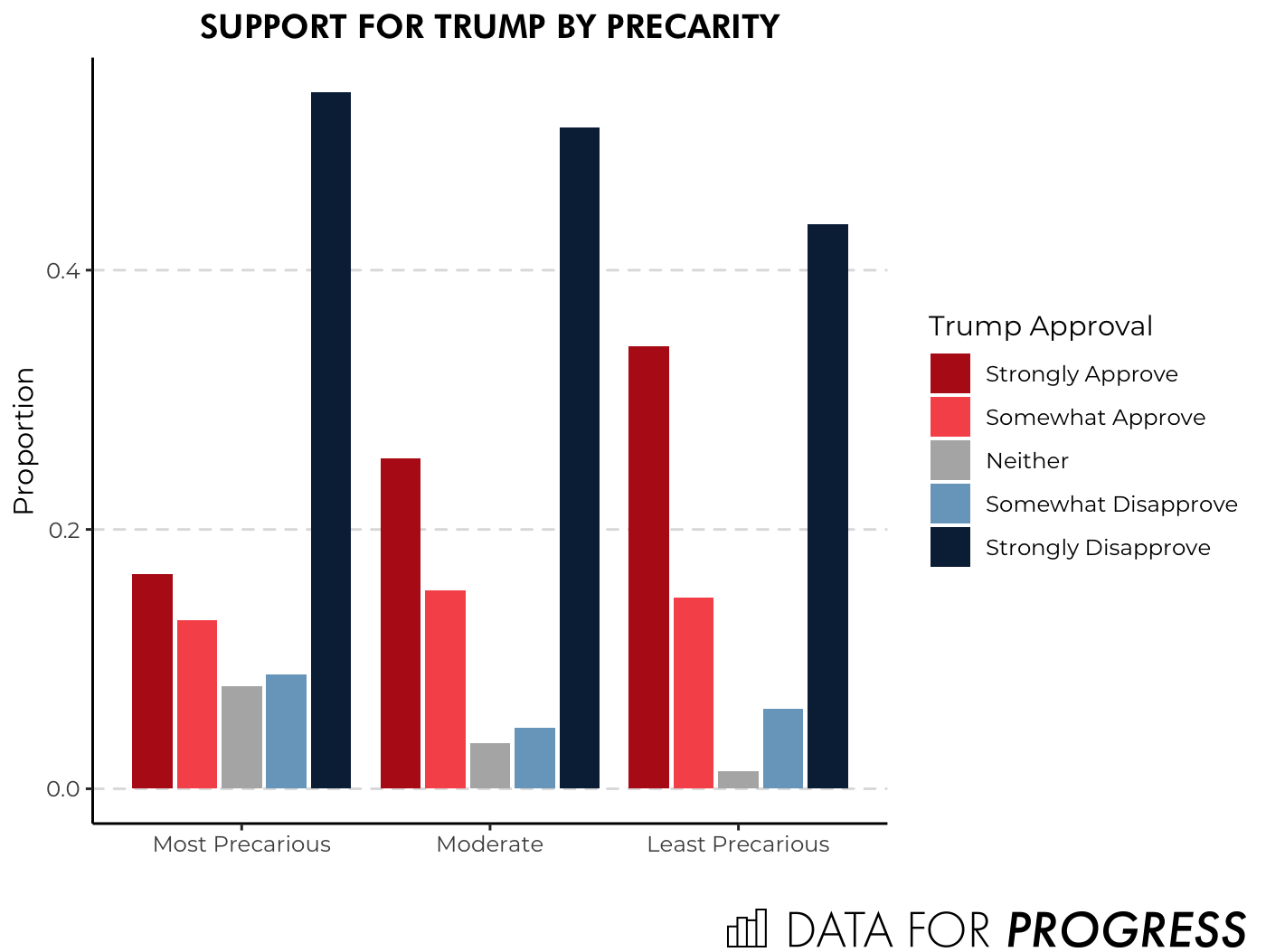

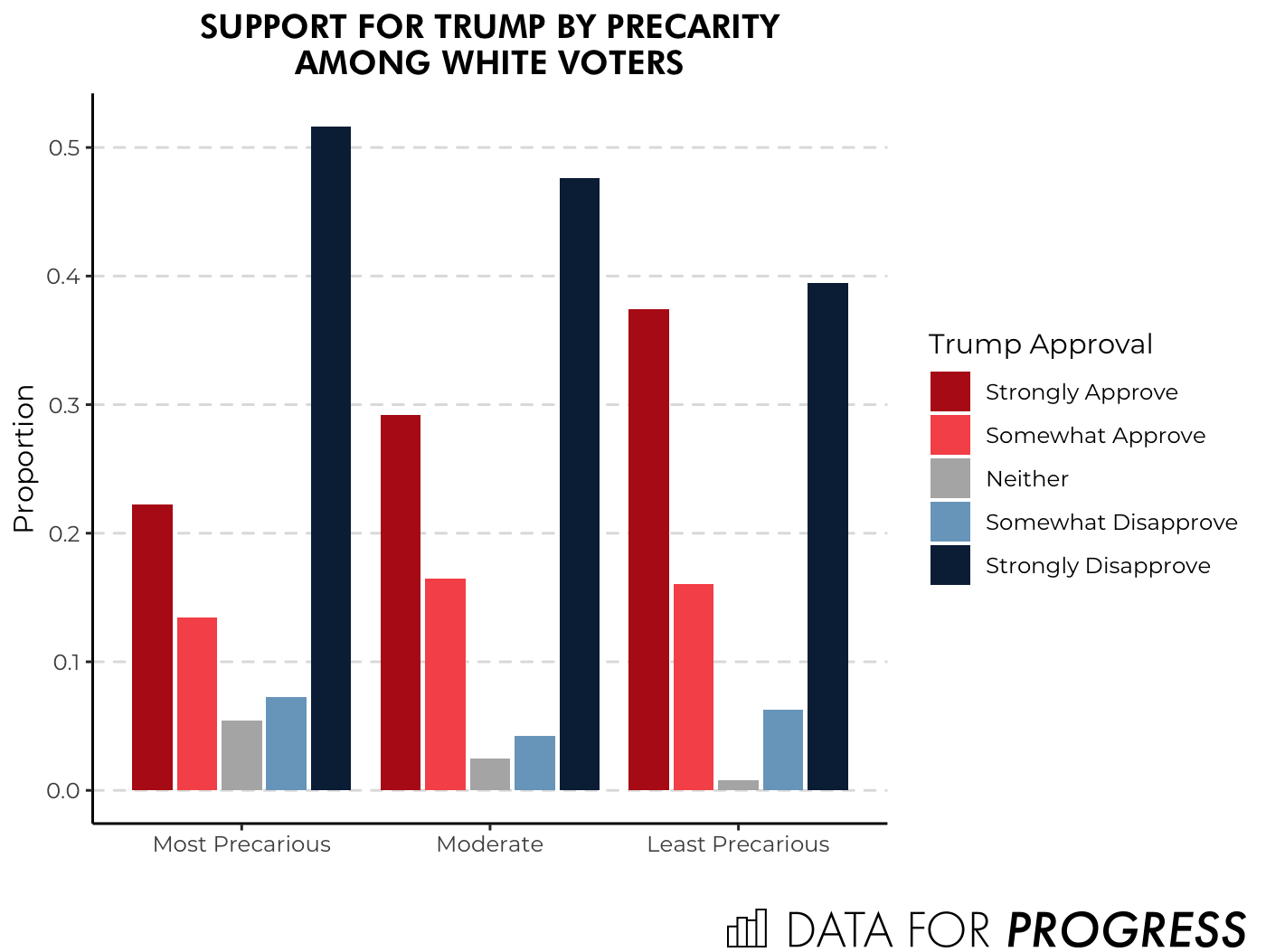

What if we use our better measure of working class -- a measure that reflects our common understanding of what it means to be working class? The relationship changes, both for all voters and for white voters. Below I plot Trump support for those at bottom, middle and top of the economic precarity (categories are just broken into a bottom third, middle third and a top third). What we see now is that those who are most precarious are actually the least supportive of Donald Trump

Working class is not a simple crosstab of race and education. Like all socially constructed terms, the definition of working class is not singular; those who decide how to measure it are able to create a narrative based on our social understanding. When exploring these types of concepts we need to be aware of how are operationalization might depart from the concepts we wish to measure. Here we’ve seen how a different (I contend better) measure of working class changes our understanding of how that working class votes.

Kevin Reuning (@KevinReuning) is an assistant professor of political science at Miami University.

Questions used for precarity scale:

Do you have . . . . YES/NO/DON’T KNOW

[fin_emerg] Money set aside in case of an emergency?

[fin_checking] Checking account at a bank or a credit union?

[fin_savings] A savings account?

[fin_cashing (reverse coded)] Place where you cash checks, other than a bank?

[fin_cc] A credit card, such as a Visa or MasterCard?

[fin_loan] Loan from a bank/credit union, such as for a car?

[fin_car] A car, truck, or other vehicle?

[fin_stocks] Stocks or mutual funds?