Neighborhood Defenders and the Capture of Land Use Politics

By Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick, and Maxwell B. Palmer

Many American cities are facing housing crises, with rapidly escalating prices placing homeownership, reasonable commutes, and even safe and secure housing out of the reach of middle- and lower-income Americans. Most economists believe that, to address this problem, we need to increase the supply of market-rate housing in these high-cost cities. Despite widespread consensus on the need to build more housing, housing shortages persist across many urban areas. Why, if most informed observers, and many city leaders, believe that we need more housing, are most cities failing to keep pace with growing housing demand?

The answer may lie in the politics of housing, and the institutions cities have created to control land use. Land use regulations can directly forbid the construction of high-density development and restrict the supply of housing. But, they may also reduce housing production by creating a political process that amplifies the voices of housing opponents. Land use regulations create opportunities for members of the public to have a say in the housing development process. Many types of housing proposals require public hearings which solicit input from neighborhood residents. This is by design. After the excesses of urban renewal, many localities turned to neighborhood-oriented processes as a check against developer dominance. But, like many participatory institutions, these land use forums may be vulnerable to capture by advantaged neighborhood residents eager to preserve home values, exclusive access to public goods, and community character.

To evaluate who participates in these land use forums, we analyzed Massachusetts zoning and planning board meeting minutes. These meeting minutes included the names, addresses, and position taken on proposed housing developments for every person who spoke at a planning or zoning board meeting across 97 cities and towns. From these documents, we can learn whether or not meeting participants support or oppose the construction of new housing in their communities, and why. Moreover, by merging these data with the Massachusetts voter file and CoreLogic Property Records, we can learn who these meeting participants are, and how representative they are of their broader communities.

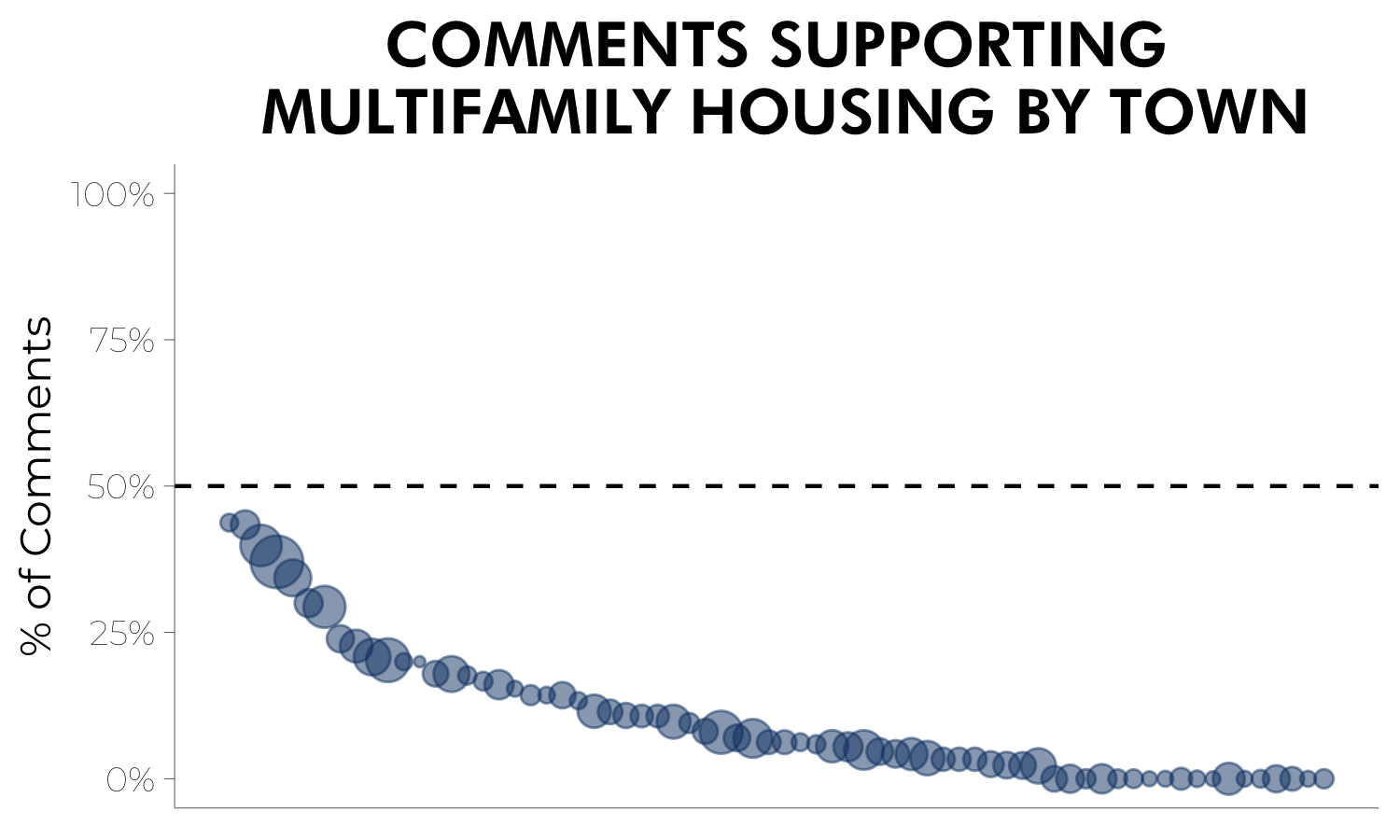

We find that only 15 percent of meeting participants show up in support of the construction of new housing. Sixty-three percent oppose new development projects. These patterns hold across every city and town we study; in liberal Cambridge, MA, a mere 40 percent of meeting participants show up in support of new housing (see Figure 1). These figures stand in stark contrast to high levels of support in Massachusetts for new housing and affordable housing, at least in the abstract. In 2010, 56 percent of voters in these cities and towns supported affordable housing in a ballot referendum.

Figure 1. Distribution of Supportive Comments by Town. Each circle represents one town in our sample; the size of the circle corresponds to the number of comments.

Meeting commenters are also starkly unrepresentative of the mass public. Relative to Massachusetts voters, they are 25 percentage points more likely to be homeowners. They are also significantly older, more likely to be longtime residents, and male. They are nine percentage points more likely to be white (see Figure 2). Latinos, in contrast, are starkly underrepresented; while Latinos comprise eight percent of voters in the cities and towns we study, they are only one percent of commenters. In Lawrence, MA—which is 80 percent Latino—1 out of 42 commenters between 2015-2017 had a Latino surname.

Figure 2. Distribution of commenters and voters by race. White voters are overrepresented at public meetings, while minority groups are underrepresented.

The meeting minutes show that these participants are highly effective neighborhood defenders. They are largely united in their opposition to new housing development, and frequently present themselves as prepared experts. They often persuade local planning and zoning officials to deny projects, or, at a minimum, delay developments by a few months with demands for more traffic or engineering studies. Other times, they threaten or actually file lawsuits, which can delay housing developments by years.

Opposition to new housing is potent and entrenched. Moreover, it is amplified in more advantaged communities where well-resourced and knowledgeable white homeowners mobilize at neighborhood meetings. This leaves poorer communities—which often feature more lax zoning codes—to bear the brunt of development pressures. This has spurred an underappreciated political consequence: a sizable fissure in the affordable housing movement. One approach to addressing rising housing costs—emblemized by California’s failed SB 827—has been to push for more lax zoning in high-cost urban cores; these measures often fail to fully consider that such policies may accelerate development pressures in communities already facing gentrification. Meanwhile, communities in which neighborhood defenders have successfully mobilized against any and all development projects—often for decades—remain largely untouched. Policy measures hoping to equitably increase the regional supply of housing must account for the political capacity of advantaged communities to combat unwanted housing developments.

Addressing these participatory disparities at meetings is not so easy. It only takes a few motivated opponents to effectively use local housing institutions. Simply making public meetings more convenient is unlikely to redress the problem. Housing developments have concentrated costs to neighbors, who face construction noise, diminished street parking, and highly visible changes to their local landscape. They will always be more motivated to turn up. In contrast, the benefits of new housing are quite diffuse; the average homebuyer or renter is unlikely to see any benefit from a small marginal increase in the area housing stock.

We need to consider broader institutional reforms at the city, state, and national levels to address the housing crisis. Our research points to the need for structural reforms that account for participatory inequalities. Concerns about housing developments and neighborhood change are widespread, and largely intractable. Efforts at reform that focus solely on motivating housing supporters to attend public meetings will likely fall flat. Instead, advocates should focus their energy on transforming how local governments review and approve housing developments.

Katherine Levine Einstein is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Boston University.

David M. Glick is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Boston University.

Maxwell B. Palmer is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Boston University.