Automatic Voter Registration Boosts Turnout Among Young and Low Income People

By Jake Grumbach (@JakeMGrumbach) and Charlotte Hill (@hill_charlotte)

Few voting reforms have generated as much buzz recently as automatic voter registration. But because this reform is so new—the very first AVR bill was passed in 2015—only now is enough data available to measure AVR’s effectiveness at bringing new voters to the polls. Below, we present the results of the very first comprehensive study of AVR and voter turnout. Our findings are two-fold: AVR modestly increases overall turnout, but it dramatically increases participation rates among young people and low-income people.

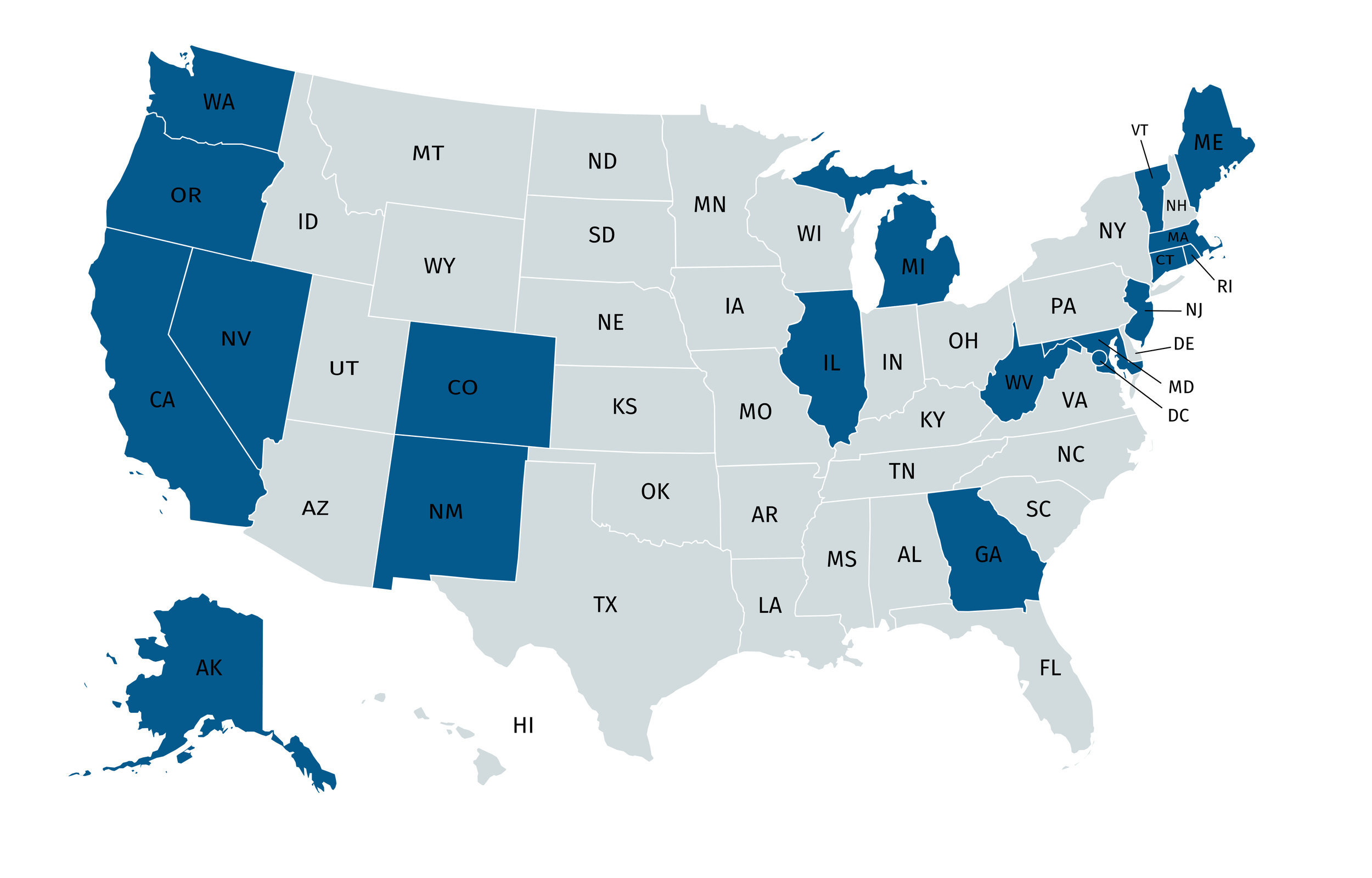

The idea behind AVR is straightforward: When a voting-eligible person visits a government office like the DMV, they are automatically added to the voter rolls—unless, of course, they choose to opt out. At the time of our study, seventeen states plus the District of Columbia had approved AVR laws (several more have passed AVR in recent months). AVR was credited with boosting turnout in 2016 and lauded for expanding voter rolls ahead of the 2018 election—but again, no research has rigorously examined this claim.

Our study asked whether living in an AVR state increased an individual’s probability of voting. We used logit and linear probability (OLS) models to estimate turnout in AVR states compared to non-AVR states, drawing on data from the Census Current Population Survey (CPS) Voter Supplement. To get at the effect of AVR laws on specific age and income groups, our models interacted an individual’s age and/or income with AVR laws. We also controlled for a range of potentially confounding factors such as an individual’s race, gender, family income, and education, as these are all known to affect the probability that someone turns out to vote. We also adjusted for election characteristics, such as whether a state had a U.S. Senate or gubernatorial election.

Our research found that AVR is, indeed, associated with increased turnout. The overall effect, while statistically significant, is modest. On average, individuals in AVR states are about 1 percentage point more likely to vote, holding constant potentially confounding demographic factors, election characteristics, and other voting laws.

Yet this average effect obscures a much larger relationship between AVR and turnout among two demographic groups: youth and low-income people. People between 18 and 24 who live in AVR states are 6.3 percentage points more likely to turn out. By contrast, AVR is not associated with increased turnout, potentially even a modest decrease in turnout among people over 65. Similarly, the likelihood of turnout among the lowest-income individuals is 4.0 percentage points higher in AVR states. For the highest earners, however, AVR is unrelated to turnout (a coefficient of -0.2 percentage points).

These results make sense. AVR’s selling point is that it eliminates the burden of registering to vote. Accordingly, AVR should primarily increase turnout among people who have a difficult time registering. Youth and low-income people fit the bill: as another study of ours explained, young people are particularly burdened by registration requirements, while other scholars have found the same for low-income individuals. By this same logic, AVR should not significantly affect the turnout of people who are already registered or who find registration relatively easy—namely, seniors and higher-income individuals, who have the resources and flexibility necessary to register, and who move less frequently than their younger and poorer counterparts. Our results are consistent with new research from Eric McGhee and Mindy Romero, who find AVR increases registration rates by 2.1 percentage points and that the effect was stronger for Latinos and young people.

These findings point to an important lesson for policy advocates: in the world of voting reform, average effects only tell us so much. Some groups inevitably benefit—or suffer—more than others. Voter ID laws don’t appear to depress overall turnout, but they do reduce the likelihood of voting for low-income and low-educated Americans. Same-day registration has a modest positive impact on turnout, but it is especially good for young people. Early voting may exacerbate existing turnout disparities by appealing primarily to high-propensity voters (who are disproportionately old, affluent, and well-educated). AVR, meanwhile, appears to have the opposite effect: it increases turnout among those least likely to participate in the voting process.

Jake Grumbach (@JakeMGrumbach) is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Washington.

Charlotte Hill (@hill_charlotte) is a Ph.D. student of public policy at UC Berkeley.