The Public Doesn’t Want to Means-Test Public Education

By Ethan Winter

To means-test higher education, or not to means-test higher education, that is the question for many Democrats running for their party’s presidential nomination. Centrist Democrats such as Senator Amy Klobuchar and former Mayor of South Bend Pete Buttigieg have argued that their college-affordability plans will not benefit the children of billionaires, unlike the plans of Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. Colin McAullife points out in an earlier blog post, Klobuchar and Buttigieg’s argument is one that can be leveled against many universal programs, such as K–12 education. (In New York magazine, Eric Levitz expanded on the pitfalls of Buttigieg’s argument here.)

Our intent with this blog post is to understand the attitudes around means-testing public programs. To do this, we polled something already universal—public K–12 education—in contrast to introducing a new, alternative program that would be means-tested. While real deficiencies exist in how the United States funds its public schools––namely, the reliance on local funding sources––we are not critiquing a real, existent proposal to means-test public high schools.

As part of our December 2019 omnibus survey, we proposed the means-testing of public high schools, asking the following: “Would you [support or oppose] requiring families earning more than $500,000 to pay for tuition to public high schools?”

We found that voters overwhelmingly opposed requiring higher-earners to pay tuition at public high school, with 59 percent opposing the proposal, 28 percent supporting it, and the remainder is not sure.

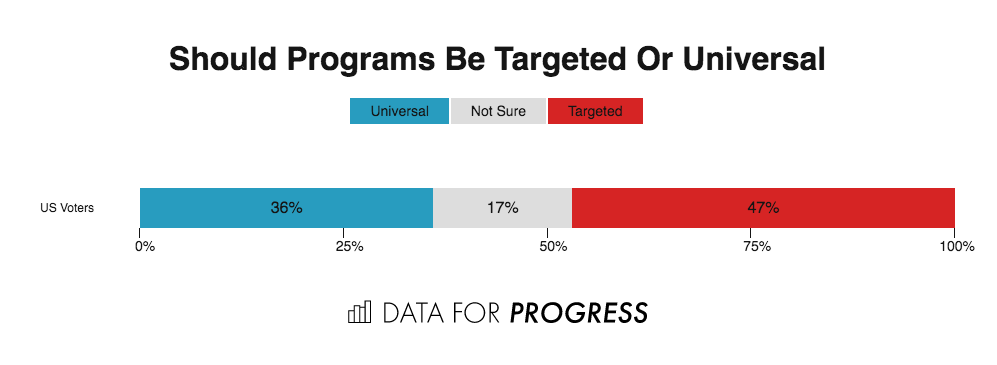

Interestingly, this result ran counter to another question we asked: “Even if it's not exactly right, which statement comes closer to your view on designing policies?” In this question, we found that 47 percent supported the answer “We should make government programs targeted, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, so that people who need benefits get them and we don't need to raise taxes as much,” compared to 36 percent who supported the answer “We should make government programs universal, like Social Security, so all Americans share in the taxes and benefits of the programs.” (The remaining 17 percent not sure.)

Next, we broke out the response to the means-testing public education by party ID. (If a person “leaned” toward one party, we grouped them with it.) By a 43 percent margin, Republican voters oppose requiring the wealthy to pay tuition, specifically, 67 opposed the means-testing proposal and 24 supported it (the rest were not sure.)

53 percent of Democratic voters also oppose means-testing public schools while 33 percent supported it (the rest were not sure). Meanwhile, a majority of independent voters oppose the proposal, 56 percent to 26 percent (with the rest not sure). Attitudes were broadly consistent whether the voter was or was not a parent.

We do find, however, that those who do not have kids under the age of eighteen support means-testing public education, while those with kids do not support it. This result is somewhat unsurprising because requiring the wealthy to pay tuition would theoretically shift the tax burden onto those with kids in the system.

We then analyzed support by whether the voter prefers capitalism or socialism. We found the strongest opposition to this proposal coming from those who prefer capitalism (68 percent opposed), though a plurality of those who prefer socialism also opposed the proposal (49 percent).

It is worth stepping back and considering both what precisely this proposal would mean in practice, and how this result may shed light on larger dynamics in American politics. Many Democrats, liberals, and socialists want what appears to be a nominally more progressive option, i.e. abandoning the current, universal payment structure for a means-tested program that would function as a tax on the rich. Therefore, it’s perhaps not surprising that many Democratic candidates feel comfortable calling for means-testing new programs for childcare and higher education; it appears to appeal to the progressive value of the rich paying their fair share. However, on closer inspection, means tests are not a particularly good way to do this in the realm of public education.

Means-testing public education would function as a tax solely on rich parents who choose to send their children to public schools—it is not a tax on all rich people. The difference between means-tested programs and normal taxes is that the former tend to narrow tax bases, as demonstrated in our survey’s example. Put differently, rather than socializing the cost between all taxpayers, means-testing tends to shift the burden onto a tighter band of people who, in this instance, are positioned as “consumers” of a particular good.

When crafting fiscal policy, the maxim of “broaden the base, lower the rates” is rarely applied to means-tested programs, as it should be. A proposal to tax people who happen to have kids of a specific age could easily be spun as an attack on families. And of course, a much smaller tax on all rich people could raise the same amount of revenue while being equivalently progressive on taxes and more efficient.

Our aim in this post was to test voters’ attitudes toward means-testing public programs. What we found is that voters support maintaining the universal structure of K–12 education, while there is also evidence that left-of-center voters are interested in finding more-progressive ways of paying for it.

Ethan Winter (@EthanBWinter) is a Senior Advisor to Data for Progress.

On behalf of Data for Progress, YouGov Blue conducted two surveys of US registered voters, using YouGov's online panel. Both surveys included US registered voters and were weighted to be representative of the population by age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, US Census region, and 2016 US presidential vote choice. This survey was fielded from December 27 through December 30, 2019, and surveyed 1,025 registered voters. The mean of the weights is 1.7, and they range from 0.2 to 6.2.