Attitudes About Norms Among Democratic Primary Voters

By Ethan Winter

The Trump era has been marked by increased attention to norms in general and their erosion in particular. Political scientist Brendan Nyhan defines norms as “the unwritten rules and conventions that shape political behavior.” The existence and support for norms, political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt argue, are necessary for the continued survival of “the republic.” Their erosion has become a point of considerable consternation among a variety of political observers.

In a Data for Progress / YouGov Blue survey of 1,619 registered voters that were likely to participate in the Democratic Primary, administered January 18 - 27, we tested support for four norms, piloting a battery that Ohio State Ph.D. candidate Jon Kingzette is in the process of developing (this is the second wave of a panel survey. See below for full details on the survey methodology).

These four items (with respondents indicating their level of agreement) are:

I would vote for a politician who spied on political opponents if that politician supports my preferred policies.

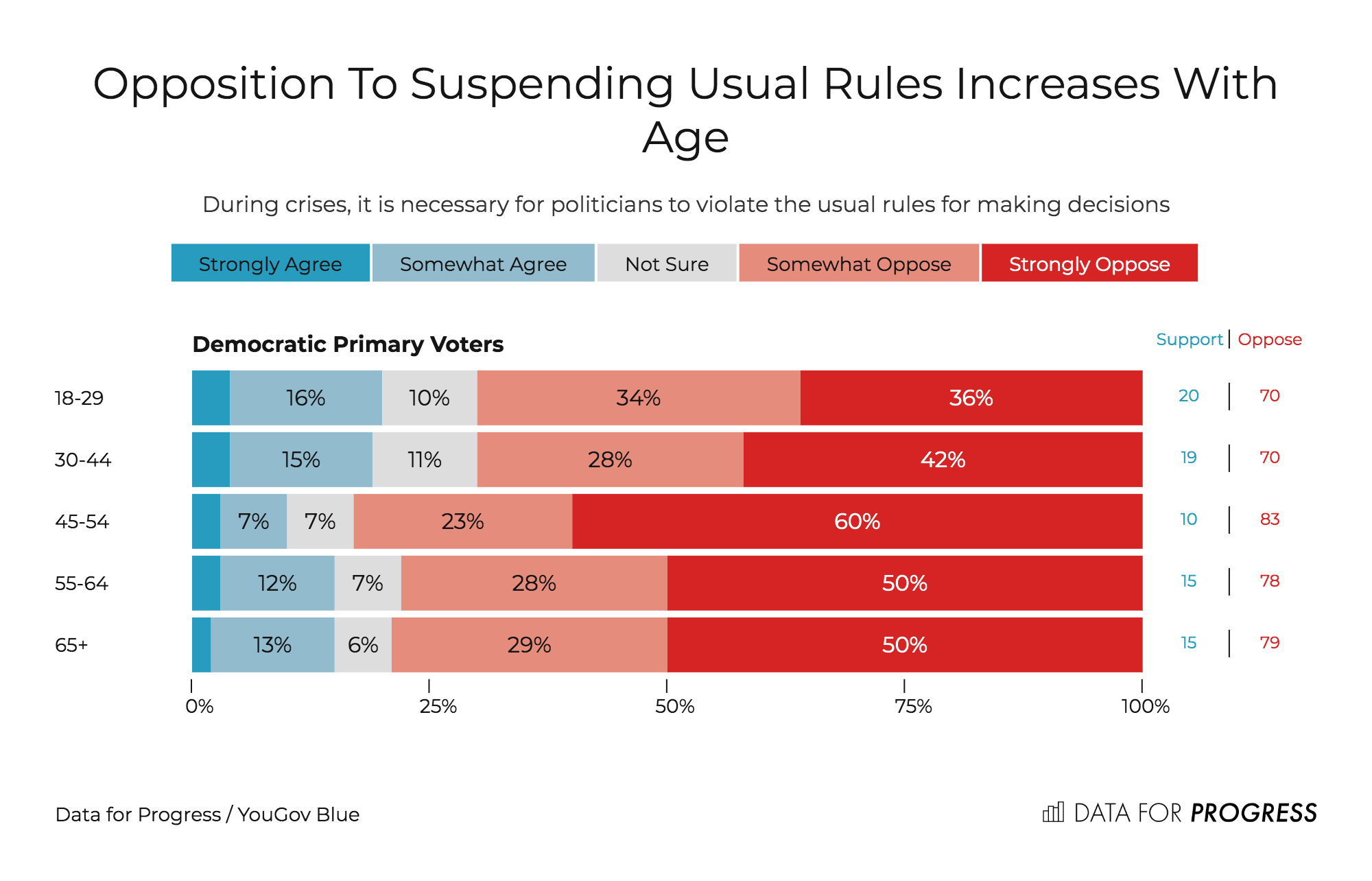

During crises, it is necessary for politicians to violate the usual rules for making decisions.

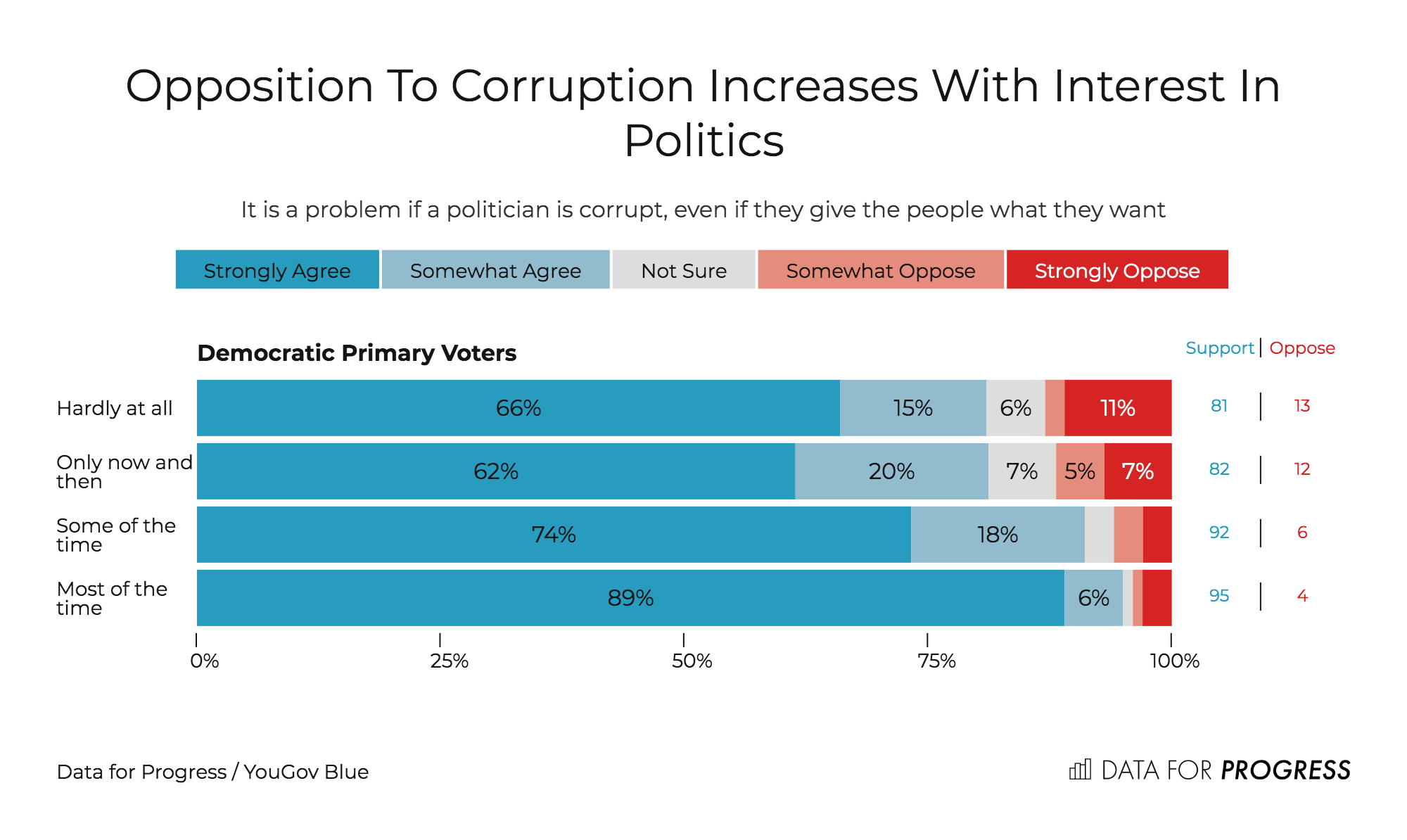

It is a problem if a politician is corrupt, even if they give the people what they want.

Politicians in the minority should abide by decisions made by the majority, even if they disagree with those decisions.

For the sake of clarity, we’ll call these norms spy, crises, corrupt, and minority, respectively. Before proceeding any further, it is also worth elaborating upon what each represents. The first has to do with cheating to win an election. The second two norms can be grouped into a general “Rule of Law” category, though they approach the subject from different directions: the second item asks if the processes and procedures of normal politics may be relaxed during crises while the probes the tradeoff between procedure and results. The fourth question examines tolerance of being in the political minority, a necessary condition for the peaceful transfer of power from one election to the next.

We found strong support among Democratic primary voters for upholding norms––for the first three norms (spy, crises, and corrupt), a large majority disagree with violating norms; support for violating the fourth norm––those in the political minority abiding by decisions made by the majority––are more mixed, with attitudes actually polarizing with an increase in age, level of education, and interest in politics. Net support for each one of these norms is as follows:

I would vote for a politician who spied on political opponents: -77 percentage points.

During crises, it is necessary for politicians to violate the usual rules for making decisions: -62 percentage points.

It is a problem if a politician is corrupt, even if they give the people what they want: +88 percentage points.

Politicians in the minority should abide by decisions made by the majority, even if they disagree with those decisions: +8 percentage points.

Democratic primary voters may be particularly attuned to norm violation because of President Trump’s repeated violation of democratic norms. To use norm three––it is a problem if a politician is corrupt, even if they give the people what they want––as an example. Trump has, on the one hand, funneled cash from his re-election campaign and the federal government itself to the properties that bear his name all while, on the other hand, confirming a historic number of judges to the federal courts.

The norm that we found the most decisive support for was that politicians should not spy on political opponents. The norm that, while still supported, had the weakest levels of support is that minorities should defer to majority decisions. The specific challenges of this question are something returned to at the end of this blog post.

Among likely Democratic primary voters, we find an age gap in support of the first three norms. Across the first three norms––politicians spying on political opponents, suspension of rules during crises, and whether policy gain outweighs corruption––younger voters are the least supportive of upholding, and each subsequent age group is more supportive of upholding. With the fourth norm––whether minorities should defer to majorities––we observe a different sort of pattern as responses become more polarized with age.

To be clear, this does not mean that younger Democratic primary voters reject norms. Indeed, we find that Democratic primary voters aged 18-29 would not support a politician who spied on their political opponents by a margin of 60 percentage points (14 percent for, 74 percent against). However, this is weaker support than we observe in older age groups. Net support for this first norm (spy) rises to 63 percentage points among Democratic primary voters aged 30-44 (13 percent for, 76 percent against), 79 percentage points among those aged 45-54 (6 percent for, 85 percent against), 82 percentage points among those aged 55-64 (7 percent for, 9 percent against), and 86 percentage points among those 65 years of age and older (5 percent for, 91 percent against).

We observe a similar pattern with the second norm––whether during crises it becomes necessary to suspend the rules of normal politics. Support for this norm, while still strong among those aged 18-29, enjoys a 50 point margin (70 percent disagreeing with the statement, compared to 20 percent agreeing). This rises to 64 percentage points (79 percent disagreeing to 15 percent agreeing).

Moving to our third norm––whether or not it is a problem if a politician is corrupt, even if they give the people what they want––we see the same pattern holds. While support for the norms remains largely steady at an 87 percentage point margin for both those aged 18-29 and 65 and older, there is a gap in the strongly agreed responses. 76 percent of those aged 18-29 strongly agree with the statement while 88 percent of those 65 and older do, a 12 percentage point difference.

Turning to our fourth norm, we see a different kind of pattern emerge, as responses to this question polarize with age. For example, when we look at responses among those aged 18-29, we see that 40 percent of respondents support this statement while 37 percent oppose it (a three percentage point margin of support. When we look at responses among those aged sixty-five and older, meanwhile, levels of support and opposition climb to 49 and 42 percentage points (a seven percentage point margin of support), respectively.

Another way to look at this polarization is to look at the breakdowns in which respondents have opinions in general and of the opinions which are strong opinions. Among those aged 18-29, 77 percent of those surveyed had an opinion, with 22 percent of these opinions strongly held. 23 percent of those aged 18-29, meanwhile, were not sure. Turning to those aged 65 and older, we see that 91 percent of those surveyed had an opinion, 35 percent of those opinions were strongly held, with only 9 percent not sure.

At this point, it is necessary to pause to clarify what this data does not show. First, that support for these four norms is weakest among younger Democratic voters does not mean that younger Democrats are less supportive of democracy as their older peers. Indeed, political theorist Corey Robin posits, in a rejoinder to Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s argument, that “democracy is a permanent project of norm erosion, forever shattering the norms of hierarchy and domination and the political forms that aid and abet them.” Thus, what our data speaks to is not support or opposition to democracy per se, but rather whether or not participants in the political sphere have been socialized to the prevailing rules of the game. That support for these four norms increases with age underscores the way in which they are learned.

This idea, that norms are learned, is further emphasized as we break down support for each of the four norms by the level of respondent’s educational attainment. The same two patterns that we saw when responses were broken down by age emerge. For the first three norms, we see that as respondents’ levels of educational attainment increases, so does their support for each of the norms. For the fourth norm, opinions polarize as the level of education increases.

The larger takeaway when looking at responses to the first three norms is not that support for democracy increases with the level of education, but rather that norms are something we learn and are socialized to support.

More evidence of the effects of individuals’ experiences is found when looking at the relationship between support for upholding norms and respondents’ levels of attentiveness to politics.We asked respondents, “Some people follow what’s going on in government and public affairs most of the time, whether there’s an election going on or not. Others aren’t as interested. Would you say you follow what’s going on in government and public affairs?” (Available responses were most of the time, some of the time, only now and then, and hardly at all.)

Respondents who pay more attention to politics are more supportive of the first three norms, and more likely to have an opinion one way or the other on the fourth, as we observed for older and more educated respondents, though the degree of polarization is not as strong here as it is for age and education.

In sum, Democratic primary voters broadly support a variety of democratic norms. This support tends to increase with age, education, and interest in politics, suggesting norms are socialized or learned. Nonetheless, it must also be clear that norms cannot be fully understood outside of the political context in which they are embedded. For instance, political scientist Jeffrey Selinger argues “objections to the legitimacy of party opposition often concern the policy substance of political contestation and not philosophical objections to partisanship alone: since the conditions attached to party legitimacy are based on policy positions… support for pluralism (or lack thereof) usually hinges on what the dissenting party or parties stand for.” Norms may well become coherent and indeed meaningful when the specific policy stakes are enumerated.

This is especially true with the last question and may explain why responses to it deviate from the first three norms (recall, rather than support for the norm increasing with age/education/political interest, attitudes polarize). While democratic government hinges on majority rule, decisions of political majorities—especially when the electorate itself has been circumscribed––can at times impinge on the basic and unyielding equality on which democracy rests. Thus, there may be some instances where a majority decision is not democratic and this choice may be made only in terms of the particularities of the case at hand and, furthermore, these circumstances may demand the violation of certain norms. In other words, the fourth norm may denote a potentially weaker form of norm violation than the first three, or a norm that requires periodic violation.

To demonstrate this, let us contextualize the findings of the fourth question in our present, polarized landscape. Republicans wield governing majorities, controlling both the Senate and White House. Yet the party does so not because they have majority backing of the electorate but because they have managed to leverage the most undemocratic features of America’s constitutional order towards their political gain. Is it then more democratic for political minorities to abide by the decisions of the Republican party? This may suggest that, as Sam Rosenfeld argues, “To effectively counter the very hatreds and pathologies that seem so endemic to th[is] age, in other words, progressives have no choice but to get into the thick of the action and fight. Doing so would only ‘worsen’ polarization in U.S. politics, but it might just save U.S. democracy.” Protecting or, perhaps, more fundamentally, promoting American democracy may require doing away with norms we thought previously safeguarded it.

Ethan Winter (@EthanBWinter) is a Senior Advisor to Data for Progress.

Survey Methodology

This survey was conducted in two waves. The first included 2,953 interviews conducted from June 24th to July 2nd, 2019 by YouGov on the internet of registered voters likely to vote in the Democratic presidential primary in 2020. A sample of 6,116 interviews of self-identified registered voters was selected to be representative of registered voters and weighted according to gender, age, race, education, region, and past presidential vote based on registered voters in the November 2016 Current Population Survey, conducted by the U.S. Bureau of the Census. The sample was then subsetted to only look at respondents who reported they were likely to vote in their state’s Democratic primary or caucuses. The weights range from 0.2 to 6.4 with a mean of 1 and a standard deviation of 0.5.

The second wave included 1,619 interviews based on recontacting respondents participating in the first wave (a 55% recontact rate). Respondents participated from January 18th to January 27th, 2020. This sample was weighted on gender, age, race, education, region, and past presidential vote to the weighted sample proportions from the first wave. The weights range from 0.5 to 4.5 with a mean of 1 and a standard deviation of 0.4.

Appendix

In this appendix, I include an extended discussion of the responses to the four items broken down by level of education and then political interest.

For the first item––whether or not one would for a politician who spied on their opponents––those with a high school diploma or less opposed this by a 68 percent margin (11 percent agree, 79 percent disagree). This margin rose to 85 percent against those with a postgraduate degree (5 percent agree, to 90 percent disagree).

For our second item––whether during crises it is necessary for politicians to violate the usual rules––net opposition sat at 56 percentage points (16 percent agree, to 72 percent disagree), with that margin rising to 67 percentage points (14 percent agree, to 81 percent disagree).

This pattern holds as we examine our third item––whether it is a problem if a politician is corrupt, even if they give the people what they want. Respondents with a high school diploma or less support this statement by a 77 percentage point margin (85 percent agree, to 7 percent disagree). This margin of support rises to 91 percentage points among those with a postgraduate degree (95 percent support, to 4 percent oppose). Also noteworthy is the steady increase of strongly agrees as the level of educational attainment rises. 74 percent of those with a high school diploma or less strongly agree with the statement, ticking up to 81 percent among those with some college, 85 percent among those with college degrees, and 88 percent among those with postgraduate degrees.

Last, as we turn to our fourth item, we see that as educational attainment level increases, responses become increasingly polarized. Among those surveyed who have a high school diploma or less, 43 percent support the statement that politicians in the minority should abide by decisions made by the majority and 35 percent oppose (ten percent margin of support). When we look at responses among those who hold postgraduate degrees, we see that support rises to 50 percentage points while opposition also rises to 40 percentage points (ten percent margin of support).

The polarization of attitudes can also be seen by looking at who has an opinion in general and of those opinions offered, how many are strongly held. Among those with a high school diploma or less, 78 percent of those surveyed had an opinion, 37 percent of total responses were strongly held, and 22 percent were not sure. Among those with a postgraduate degree, meanwhile, 90 percent of those surveyed had an opinion, 33 percent of total responses were strongly held, and 10 percent were not sure.

Below are the charts detailing responses to the four norm items broken down by interest in politics. Those surveyed were asked the following question, “Some people follow what’s going on in government and public affairs most of the time, whether there’s an election going on or not. Others aren’t as interested. Would you say you follow what’s going on in government and public affairs…” and were given four possible responses: “most of the time,” “ some of the time, “only now and then,” and “hardly at all.”