Black Women Best

By Janelle Jones

If history has taught us anything, it’s that Black people, particularly Black women, are among the last to recover from economic recessions, and the last to reap economic benefits during periods of recovery or growth. So when policymakers focus on helping the average worker find a job and the average family get out of poverty, and then declare the job done when that happens – they are necessarily leaving Black women still in crisis. But if they reorient their thinking to put Black women first, and promote policies that focus on pulling Black women out of the recession and into prosperity – then they will necessarily be lifting everyone up in the process. I call this economic ideology “Black Women Best,” and I believe it can be a powerful tool to help our economy truly recover from economic downturns.

Here are the facts. In every economic recession since the 1970s, Black women consistently had an unemployment rate that was significantly higher than white men. In some cases, as in the early 1980s recession, Black women had an unemployment rate double that of white men. Equally concerning, during times of recovery, Black men and women’s unemployment rate declined at a significantly slower pace than their white counterparts. It couldn’t be clearer: Black women are and have been excluded from the economy for decades regardless of periods of booms or busts.

Black women haven’t been left behind by accident either. The economic state of Black women in the U.S. is a result of deliberate policy choices made by wealthy white men in positions of power. These decisions perpetuate systemic racism and allow those in power to hoard their wealth while eliminating wealth-building for Black women and other people of color.

We see this clearly in the current COVID-19 recession, which has had disproportionate health and economic impacts on Black workers and families. Yet, conservatives in the U.S. Senate have refused to pass legislation that would extend unemployment insurance and have refused to move key legislation to provide Americans with a more stable source of income that would empower lower-income communities and communities of color with the necessary tools to endure the current economic recession.

The legacy of economic exclusion of Black women is woefully long and staggeringly expensive. Michelle Holder estimates that the interaction of gender and racial wage gaps cost Black women $50 billion dollars in 2017 alone. Today, Black women earn 61 cents for every dollar a white man earns yet Black women historically have had the highest labor workforce participation rate when compared to their white counterparts. Additionally, there are discrepancies in leadership in both political and corporate roles, and educational attainment for Black women. For instance, Representatives Jahana Hayes and Ayanna Pressley became the first black women elected in their respective states. In corporate settings only two Black women, Ursula Burns and Mary Winston, have led a Fortune 500 company in our nation’s history. Not to mention other forms of exclusionary policies that harm the Black communities like gentrification, police brutality, or excessive discipline in schools. Combined, the intentional policies to remove Black men and women from reaping economic benefits not only hurts Black lives, but also hurts the entire economy.

Decades worth of extraction and systemic racism has caused detriment across communities and within our economy. When the experiences and worth of Black women, and other marginalized communities, are devalued, disempowered, or excluded, this negatively affects our collective ability to produce shared prosperity. There is no validity to race neutral economies or race neutral policies. If policymakers continue on their current course, we will remain stagnant as an economy and will pay dearly for ignoring the experiences and economic prospects of our most marginalized workers and communities.

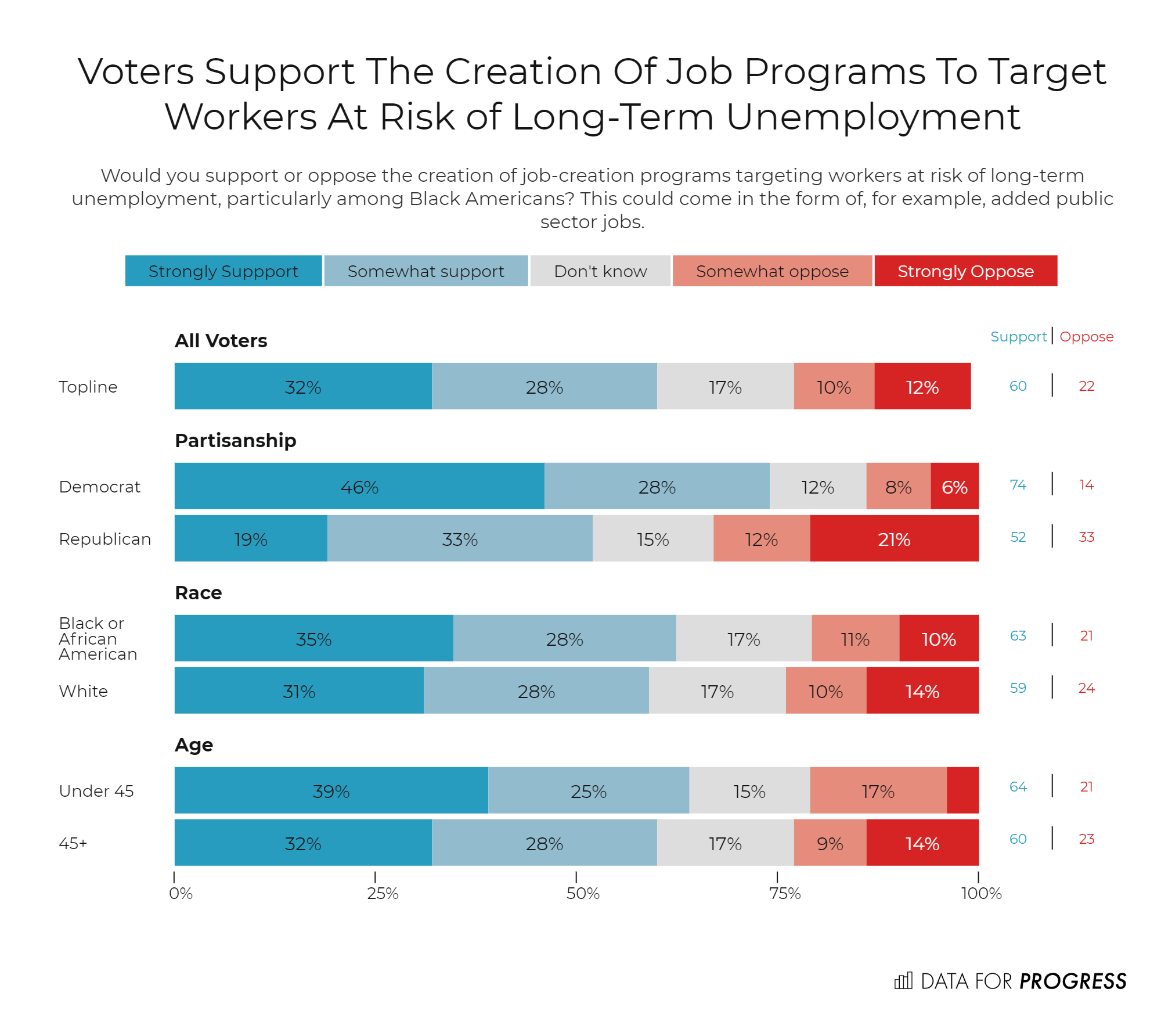

As part of a July survey, Data for Progress tested two proposals that draw upon this framework. First, we asked voters if they would support the development of a jobs-creation program that would target workers at risk for long-term unemployment, particularly among Black Americans. We found high levels of support for this proposal. Overall, voters supported this proposal by a 38-percentage-point margin (60 percent support, 22 percent oppose). It enjoyed bipartisan support with majorities of both voters who self-identify as Democrat and Republican backing it. Both white and Black voters support the idea, as well as those both over and under the age of forty-five.

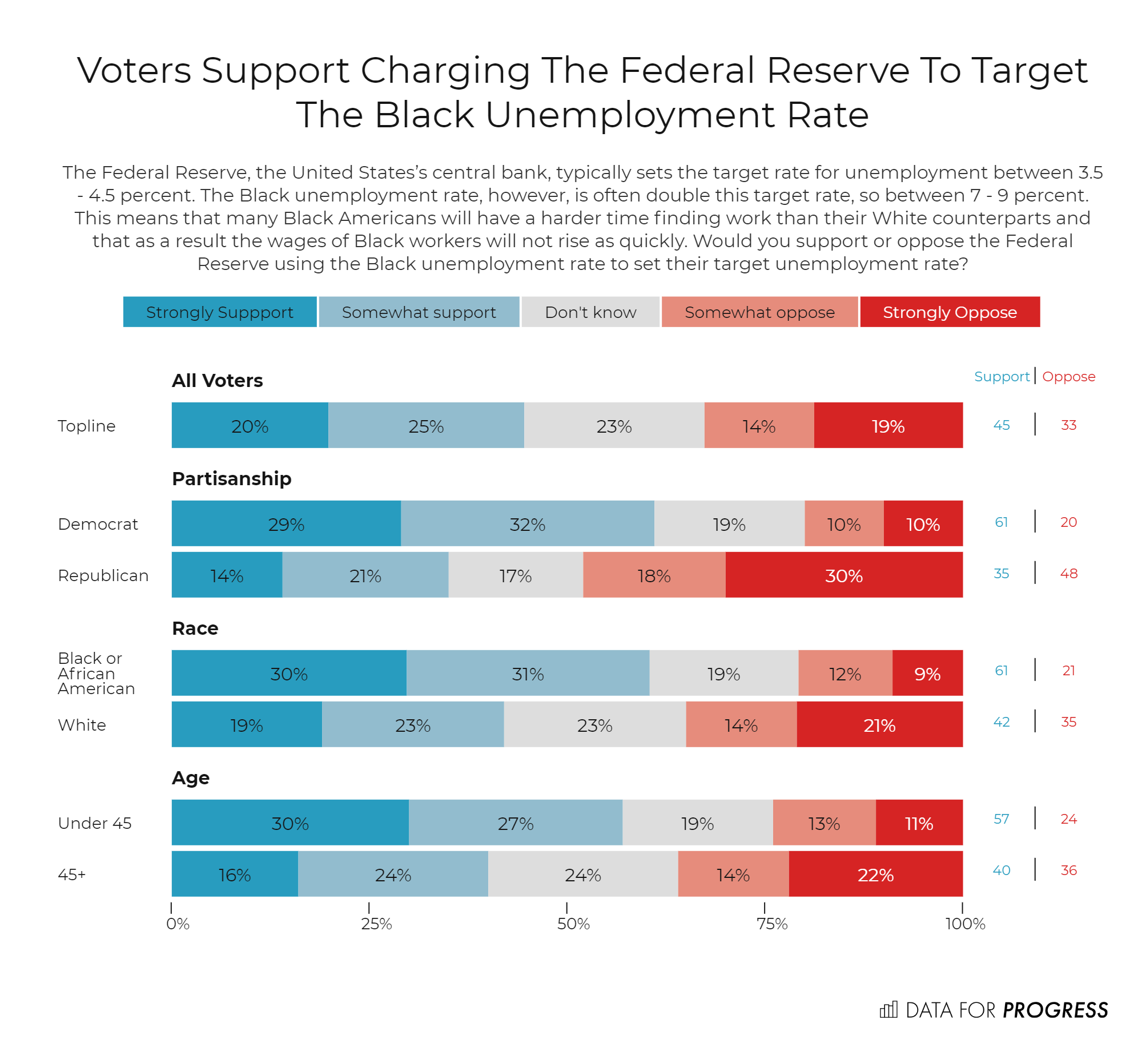

Next, we asked voters if they’d support the Federal Reserve targeting the Black, rather than more general, unemployment rate. We, again, found considerable support for this. Among all voters, it enjoyed a 12-point margin of support. We found that this proposal enjoys support among Democrats (61 percent support) and a not insubstantial number of Republicans (35 percent support). Both white and Black voters support the proposal as well as voters over and under the age of forty-five.

But if policymakers can reorient their thinking toward a “Black women best” framework, we can shift the economic worldview to include and elevate Black women and other people of color in ways that will benefit everyone. A “Black women best” ideology would lead to enacting deliberate strategies of inclusion to create a stronger economy so that our most marginalized can thrive. It would center Black women in conversations and policy actions. It would ensure that Black Women and their needs are centered -- they are being paid fairly, attaining new levels of education, surviving in hospitals, building wealth, and more. And by doing so, it would ensure that the floor gets lifted for everyone, and the economy as a whole benefits from strong and widespread growth and prosperity.

Janelle Jones (@janellecj) is the Managing Director of Policy & Research, Groundwork Collaborative

Methodology

From July 10 through July 12, 2020, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1,390 likely voters nationally using web-panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is +/- 2.6 percentage points.