DFP 2022 Polling Accuracy Report

Our Accuracy

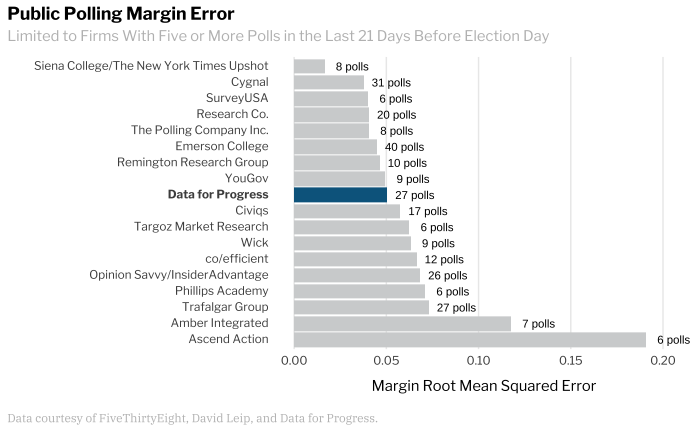

During the 2022 general election cycle, Data for Progress released public polling in key Senate and governor races. We improved our 2020 polling error, nearly halving our root mean square error (RMSE), a measure of error that penalizes larger misses. Looking at the polls in the general election cycle, our polling margin bias was 1.9 percentage points toward overestimating Republican vote share. In total, we ended the cycle with a record of accuracy and minimal bias among multistate public pollsters.

Data for Progress was one of the top public firms that were more accurate than average. The RMSE of our polling margins this cycle was .05, compared to an overall RMSE of .064. As of November 30, the Cook Political Report reports the national popular House vote as R+3, which is 1 point in margin away from our final poll of R+4.

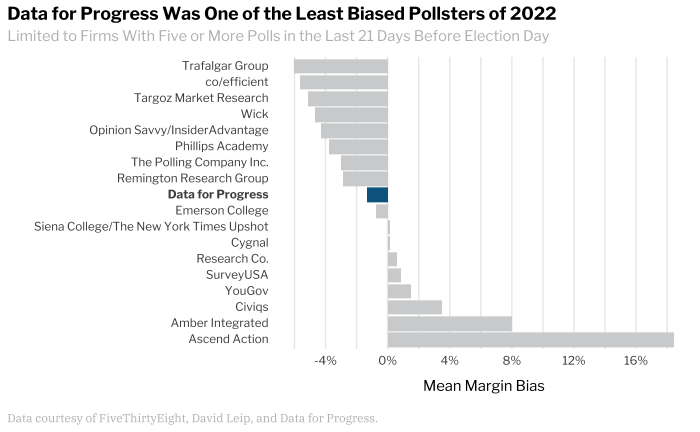

Our polling showed a 1.9-point average polling bias toward Republicans, and was among the least biased when compared to other public pollsters (below) of the cycle. Of course, averages aren’t perfect measures: Our smallest biases were in the Nevada and Oregon gubernatorial races, -0.05 and 0.04 points, respectively; and our largest margin biases were in Senate races, 9 points toward Democrats in Florida and 9 points toward Republicans in Vermont.

Despite lowering our error from the 2020 cycle, there remains room for improvement. In the 2020 general, and our work in primary elections, SMS proved to be our most reliable mode for surveying elections.

However, in 2022, SMS shows a relatively consistent 5-point margin bias toward Republicans. This is the opposite of the bias we observed in 2020 toward Democrats as a result of higher rates of within-partisan-dynamic nonresponse biases.

In this report, we outline potential drivers of our polling error as well as ways we can improve our accuracy going forward, with an increased focus on recruitment and limiting the presence of hard partisans and eager survey respondents.

Mode Biases

While Data for Progress surveys are mixed-mode with data being collected from a variety of sources, text-to-web (SMS) and web panel polling are our traditional modes of data collection.

We use SMS for a couple of reasons. As Nate Cohn has written in the New York Times, live caller response rates have fallen below half a percentage point. A response rate this low raises costs and the risks of nonresponse biases. While SMS surveys suffer from similar problems, our average in-cycle response rate is almost double that of live caller, hovering at just under 1 percent.

This response rate of more than double that of a live caller survey is just one of a handful of advantages SMS enjoys. SMS also allows for both random sampling and the ability to match back to a voter file. However, a trend we have observed is that SMS recruits too many motivated or engaged hard partisans, and not enough persuadable voters. Our analysis finds this feature of SMS makes it a more reliable mode in polling primaries, generally low-turnout events that high-engagement and committed partisan voters typically dominate, than general elections.

In 2020, our analysis indicated that SMS showed a small bias toward Democrats. In 2022, this trend reversed. In fact, our SMS captured more persuasion from Biden voters than from Trump voters (Biden voters switching to Republican candidates this cycle). This implies that Democrats were switching from their party when voting at higher rates than Republicans, which is likely not what occurred in the election.

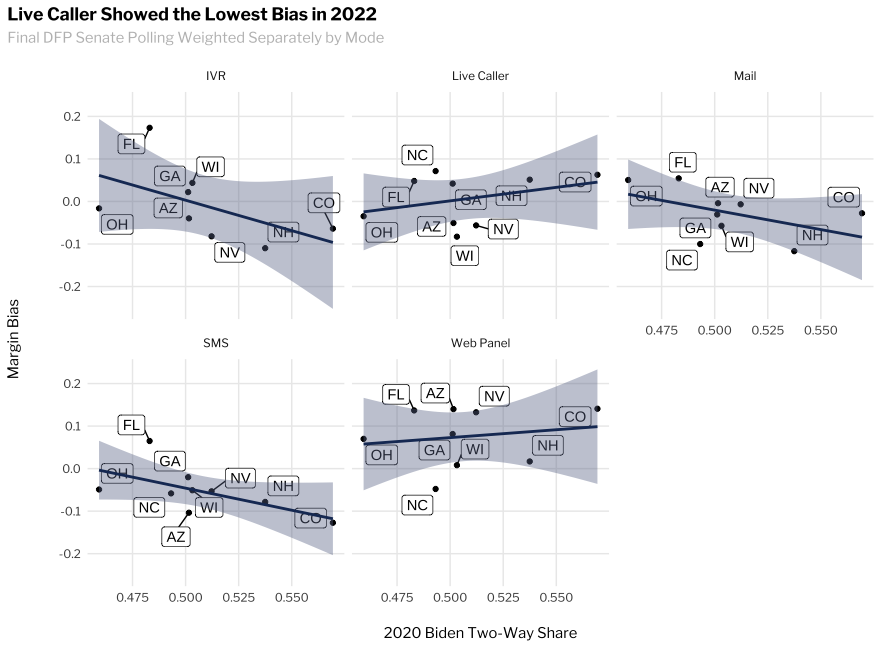

In the following graphs, we track how Democratic margin bias shifted depending on the 2020 Democratic performance in each state across modes. A shift up the vertical axis indicates a larger bias toward Democratic candidates. In other words, a downward-sloping line indicates overestimating Democrats in conservative states and Republicans in liberal states.

For this analysis, we have limited ourselves to states for which we could also use a second set of weights as a point of comparison: Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, New Hampshire, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

When separating each mode to be weighted independently, our live caller polling showed the lowest polling margin bias, an average of 0.5 points toward Democrats. SMS and web panels are more consistent but exhibit opposing biases (SMS favors the Republican, web the Democrat). Both interactive voice response (IVR) and mail both show biases that favor the minority party in a given state. These findings indicate that we have work to do to combat the modal biases, but that SMS and web panels are still promising modes given their relatively consistent bias.

Our analysis of our weighting bias is subject to change once the voter file is updated and we no longer need to rely on our turnout modeling. To help support our analysis, we took the step of reweighting our surveys with alternate targets from a respected progressive analytics firm. We present these results in the chart below. The results of reweighting show that different turnout modeling could have helped to reduce our bias, but that our conclusions about how the modes performed remained unaltered.

Special Elections

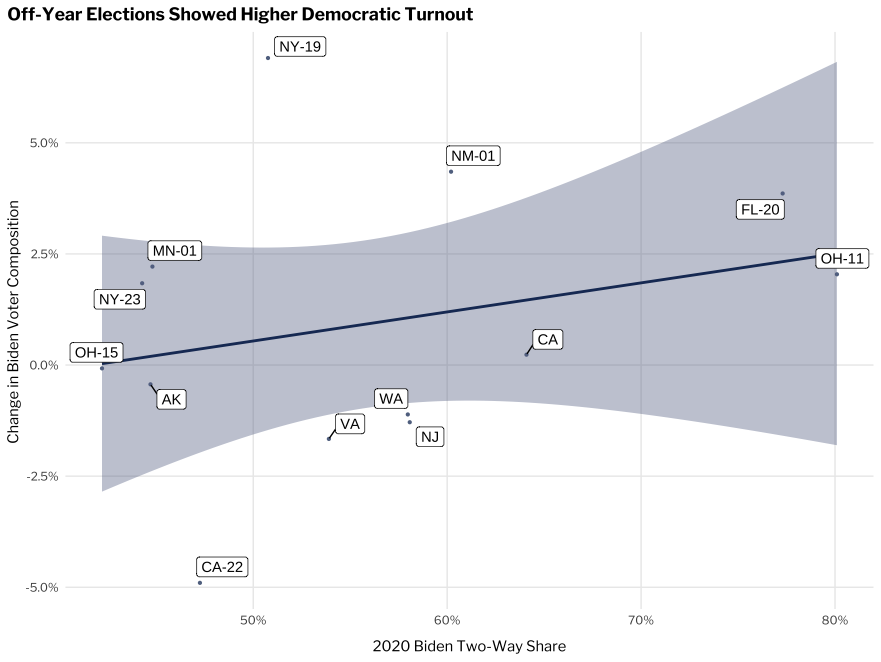

Earlier in the 2022 cycle, our polling of the NY-19 special election significantly underestimated the performance of Pat Ryan, the Democratic candidate. At the time of this election in August, we projected that the share of the electorate that voted for Biden would be similar to the percentage of the vote he received in 2020.

Using individual vote history and our in-house vote choice model (built using ecological inference), we estimate that the NY-19 special electorate swung to be nearly 7 points more friendly to Democrats than the district’s electorate was in 2020.

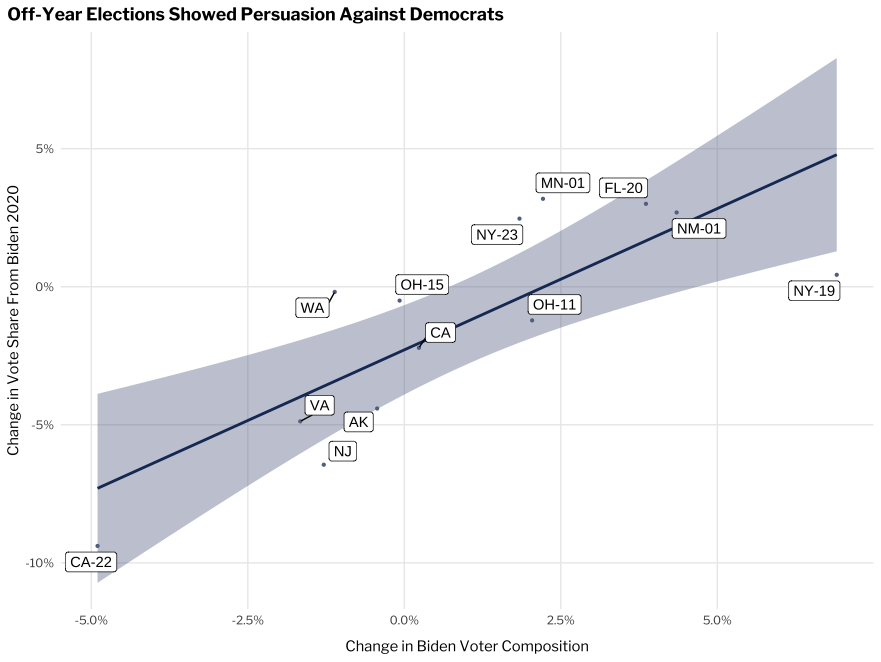

In the chart below, we show the output of this model for our races where individual vote history is now accessible, including the 2021 gubernatorial elections in Virginia and New Jersey, the California recall, and the Washington jungle primary elections.

The horizontal axis shows the estimated two-way Democratic vote share in the 2020 election, and the vertical axis shows the percentage point swing in turnout toward or against Democrats. Moving up the vertical axis indicates that the given electorate was more friendly to Democrats relative to 2020, and the horizontal axis shows Biden’s two-way vote share in the district.

While Democratic turnout was strong in the special elections, we saw an average persuasion penalty of 2.5 points against Democrats. In other words, Democrats needed to make the electorate 2.5 points more Democratic to match Biden’s performance.

This is likely because voters who had previously voted for Biden were switching their votes in the off-year elections, which set our expectations low for performance in the general election.

Candidate Effects

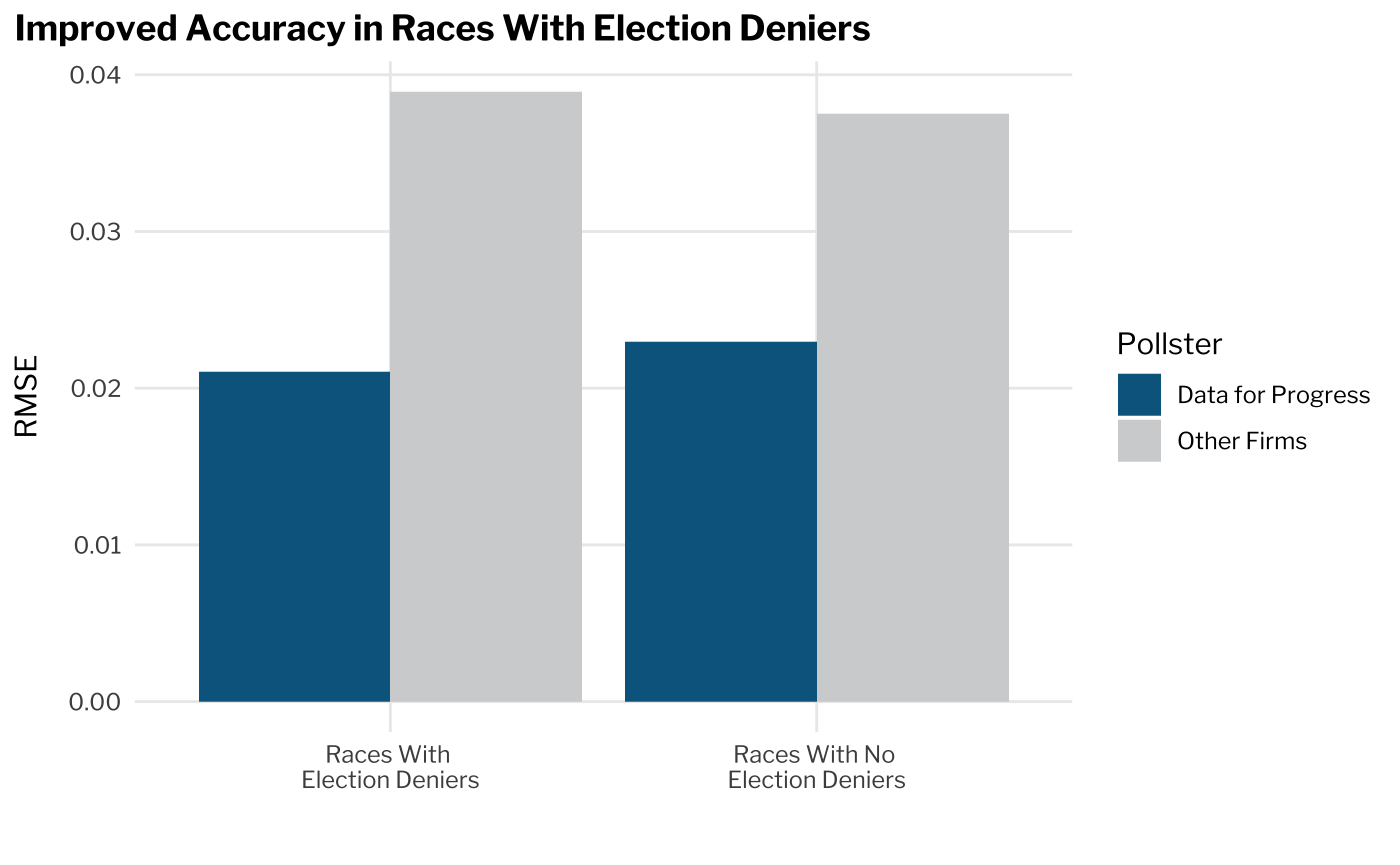

There was a general tendency across pollsters to overestimate the performance of Trump-endorsed candidates and election deniers in the 2022 midterms. While Data for Progress polling was more accurate in predicting vote share in races without extreme right-wing candidates, our errors more consistently skewed in the direction of overestimating right-wing candidate performance, resulting in more accurate, but more biased polling in these races.

Our polling of races with Trump-endorsed candidates, election deniers, and incumbents all maintain lower errors than external pollsters. In fact, all polling was more accurate in races with Trump-endorsed candidates.

Overall, we see that Data for Progress polling performed better than competitors and has improved relative to our own polling in the last election cycle. However, higher polling errors in races without extreme candidates and incumbents highlight a path for improving our accuracy going forward.

Nonresponse

When pollsters talk about nonresponse, they mean a variety of biases which refer to the tendency of various voter groups being more or less likely to respond to a survey. The most common form is called “observable” nonresponse, which means we have ways of measuring it and can account for it in weighting. A classic example is that at different times in a political cycle, Democrats or Republicans will typically become more, or less, likely to respond based on their national party performance. This is why many polling firms use partisan weighting targets like vote recall or party registration.

Another form of nonresponse is “nonignorable, nonobservable” nonresponse. This refers to a pattern of response biases that we cannot ignore because they are related to vote choice but cannot be measured. The inability to measure this kind of nonresponse is key because it means we cannot use weighting to account for the bias.

As our research into the nonignorable, nonobservable nonresponse continued over the course of the cycle, we repeatedly found ourselves coming to the same finding: Past survey response is a strong predictor of future response propensity. This pattern holds even after accounting for standard weighting variables. The consequence of this is that one of the most valuable indicators we have about a survey respondent is their response itself.

Not only is past response predictive of future response, but participating in polling appears to be a unique form of political engagement. For example, in our survey data, simply responding to more than one survey means you’re more likely to approve of Biden than your demographic peers even when controlling for things like being a primary voter or making political donations.

This work benefits tremendously from findings published by academics like Erin Hartman, Melody Huang, Valerie Bradley, and Meg Schwenzfeier, who have documented and tackled survey nonresponse in academic settings and as pollsters. We plan to apply these findings by focusing our work on developing novel ways of recruiting respondents to our surveys, and taking time to build complex models of both general and mode-specific survey response.

As discussed above, SMS and web panels show biases but they are consistent in electoral settings, while policy polling is not subject to the same biases. What is becoming increasingly clear is that probabilistic sample selection, with the largest possible reach, is worth the investment. We will continue to invest in using SMS, live caller, and web panels in coordination with each other to reach more low-engagement voters.

One way we are trying to optimize our outreach is by pulling one sample and using multiple modes to collect responses. In other words, we try to collect responses first via SMS, then recanvass the sample with live caller or IVR, and then, finally, use mail-to-web.

We’ve also begun work on response models that are not conditional on mode, to predict a general propensity to take surveys, which we can combine with mode-specific response modeling to target voters who are the least likely to respond overall and those least likely to respond to a specific mode.

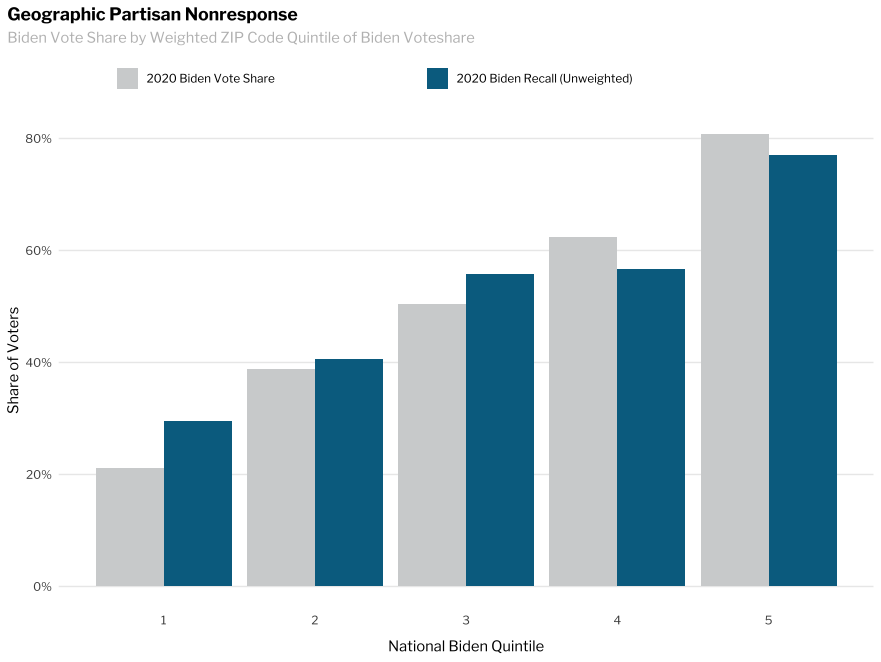

We have made strides in controlling for the partisan nonresponse in our polling, including leveraging our ZIP code-based “Trump factor” that we first identified in 2020 in our sampling process. In our 2020 analysis, we used results at the ZIP code level, bucketing ZIP codes nationally by their Biden vote share so that they are equal in the voting population. This ensured that we spent more energy on recruitment than on weighting.

The chart below illustrates that the recalled 2020 vote share among our respondents is too favorable to Biden in the lowest quintile, while not being favorable enough in the highest.

Some of our approach to nonresponse has been to develop more complex weighting targets that use the joint distributions. Specifically, we’ve focused intently on recruiting more representative samples, using up to five modes in our final 2022 surveys. We’ve also added controls in our sampling for the relative partisanship of our respondents (recruiting more rural Trump voters from the lowest Biden quintile) and by interacting models of response and turnout (oversampling voters who are both unlikely to respond to our polling and very likely to vote).

Conclusion

As we dive deeper into our polling accuracy this cycle, we will continue to investigate and share our findings, including on weighting of recalled vote versus party registration, capturing partisan defectors (swing voters, or persuadable voters), and examining how we are modeling our turnout environments. Most importantly, we are working to develop a rich model of survey response to make voter outreach more targeted toward those least likely to respond, reducing the presence of engaged partisan respondents.

We also plan to spend time learning to capture more contextual variables and information about issue salience in specific races, and on building a rich profile of response propensity to improve our sampling and contact methods.

We still have room to improve — and are orienting ourselves to catch problems before they appear. This year we improved on our error in 2020, adding more modes and adding new forms of addressing nonresponse. Looking forward, we are committed to being an accurate, transparent, and reliable pollster for the progressive movement.

Authors

Johannes Fischer, Lead Survey Methodologist

Cecilia Bisogno, Survey Methodology Engineer

Ethan Winter, Lead Analyst

Ryan O'Donnell, Electoral Director

This report wouldn’t have been possible without the work of Abby Springs, Brendan Hartnett, Brian Burton, Charlotte Scott, Colin McAuliffe, Danielle Deiseroth, Evangel Penumaka, Grace Adcox, Isa Alomran, Jason Katz-Brown, Kevin Hanley, Kirby Phares, Lew Blank, McKenzie Wilson, Payton Lussier, Phoenix Dalto, Sean McElwee, Tenneth Fairclough, Tim Bresnahan, Zach Hertz, and the entire Data for Progress team.