Voters Want State and Federal Lawmakers to Lead on Carbon Dioxide Removal

By Celina Scott-Buechler and Toby Bryce

After years of political inaction on climate change, preventing catastrophic global warming will rely on ambitious climate action at every level of the U.S. government. We must decarbonize the energy sector, and the global economy more generally, as quickly and as completely as possible. However, emissions from certain sectors — such as agriculture, shipping, and aviation — will be difficult to abate in a climate-relevant time frame. As such, there is clear scientific consensus, restated in very stark terms in the recent IPCC AR 6 Working Group III Report, that carbon dioxide removal (CDR) will be required at immense scale — 1.5 billion to 3.1 billion tons per year or more — by midcentury to keep global warming below the 1.5 degrees Celsius or even 2 C benchmark enshrined in the Paris Climate Agreement.

Billions of tons of CDR, defined by the IPCC as “anthropogenic activities removing CO2 from the atmosphere and durably storing it in geological, terrestrial, or ocean reservoirs, or in products,” will not magically manifest in 2045 when we need them. Nor will the global economy achieve this scale of CDR without significant support from the public sector. World governments — local, subnational, and national — must start investing in CDR to provide this support now, and they must make sure that it is done equitably and effectively. Previous Data for Progress polling illustrates that, especially in light of the recent IPCC report, voters are ready for government leadership on climate action, and broadly support including CDR alongside deep decarbonization.

The New York Carbon Dioxide Removal Leadership Act (CDRLA) marks the first of its kind: a state-level bill aimed at advancing CDR deployment in the immediate term to ensure it’s ready to be scaled up when we most need it and done so in a sustainable and progressive way. The act authorizes the creation of a state-run advance market commitment for durable carbon removal, starting with a very small amount (10,000 tons in 2024) that doubles each year through 2029. The state’s CDR purchases would be fully funded over the bill’s initial five-year authorization period by the repeal of a corporate tax subsidy on fossil fuel for commercial aviation, one of the “hard-to-abate” sectors identified in the state’s landmark 2019 net-zero policy, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. The legislation employs an innovative reverse auction mechanism to encourage competition, drive down costs, and ensure that the state gets good value for its investment.

New York’s CDRLA is standards-based — requiring clear additionality (ensuring that the removals are in excess of what would have occurred without the policy intervention), a minimum 100-year durability, and third-party measurement and verification — and is otherwise non-prescriptive in terms of what carbon removal projects are eligible for procurement. These may include:

biomass-based pathways, which rely on plants’ abilities to capture carbon dioxide through photosynthesis;

enhanced rock weathering and other mineralization, which accelerate rocks’ roles in the carbon cycle;

ocean-based approaches, which enhance ocean processes to draw down CO2;

direct air capture, which filters CO2 from open air.

However, the CDRLA does not pick winners, and instead allows this diverse set of carbon removal methods to compete to deliver the most effective and economical climate outcome.

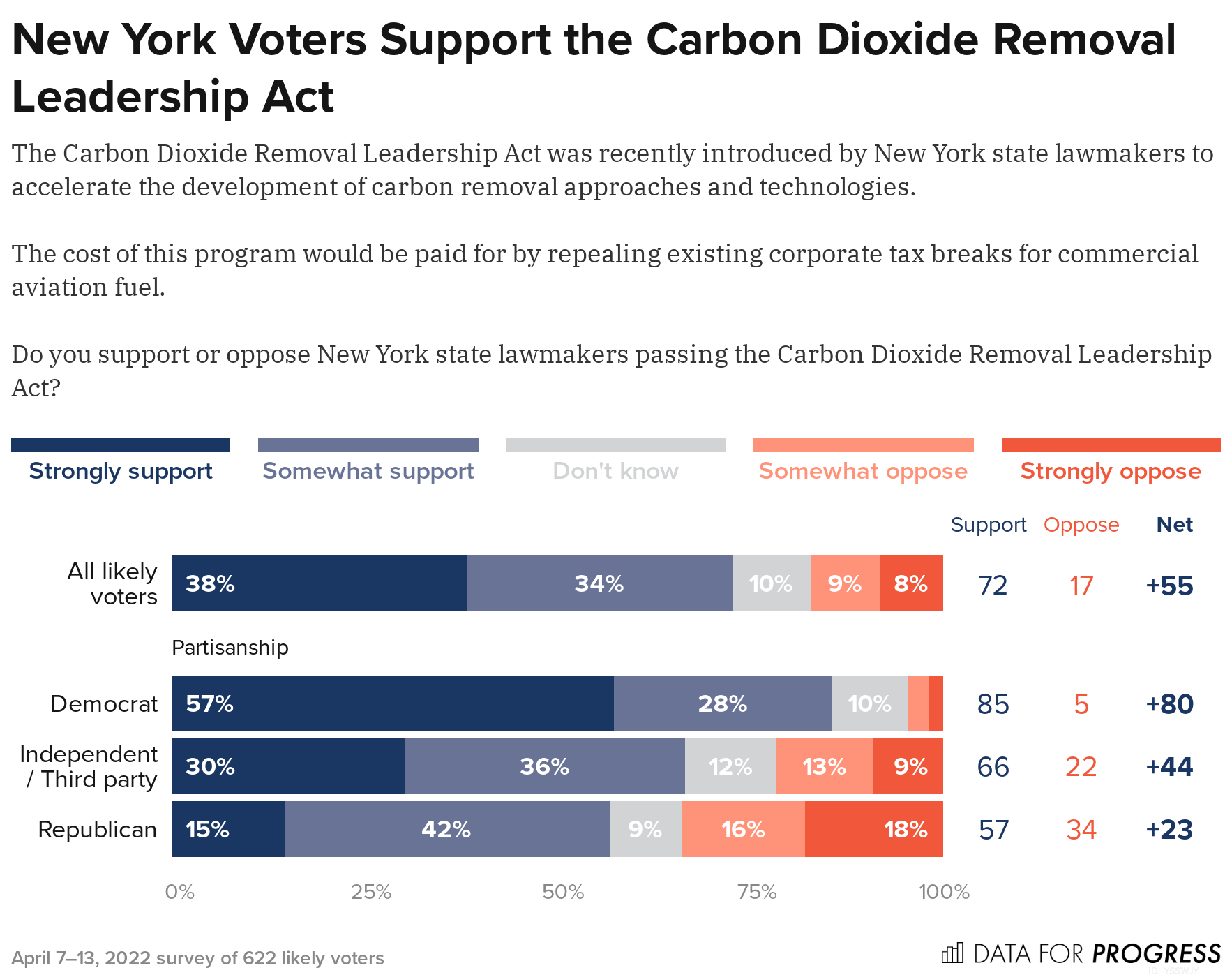

And the New York CDRLA is popular, too: recent Data for Progress polling in New York state finds that 72 percent of voters approve of the state legislature passing a bill to accelerate the development of carbon removal approaches and technologies. This includes 85 percent of Democrats, 66 percent of Independents, and 57 percent of Republicans.

At the national level, a federal CDRLA was introduced to Congress by Representatives Paul Tonko (NY-20) and Scott Peters (CA-52) in April. Whereas the New York CDRLA is method-neutral, the federal version focuses on technology-based carbon removal — such as direct air capture (DAC), which removes carbon from open air. The bill would prompt the Department of Energy to “remove carbon dioxide directly from ambient air or seawater” in increasing volumes each year, beginning with a goal of 50,000 metric tons in 2024 and working up to 10,000,000 metric tons by 2035. It also sets thresholds for the economic feasibility of carbon removal options, specifying $550 per ton as an initial upper bound and gradually decreasing that cost to $150. The combined volume and cost targets could help to decrease the costs of currently expensive methods of carbon removal, enabling large-scale market adoption. The legislation also explicitly requires rigorous monitoring, reporting, and verification, which are important tools to ensure that we actually remove the volume of carbon emissions we think we’re removing.

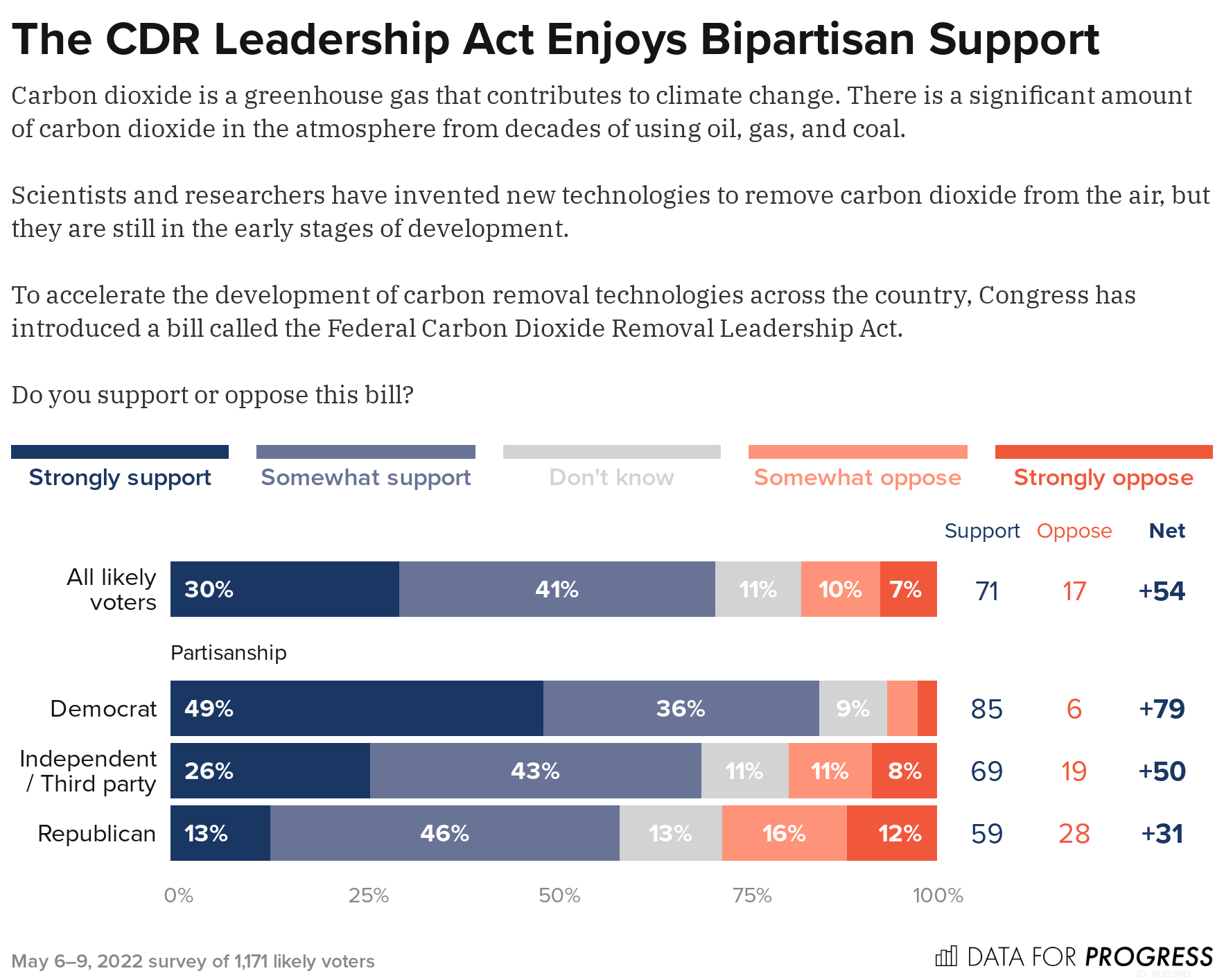

Similar to the New York bill, the federal CDRLA is popular among national voters. Seventy-one percent of likely voters support Congress passing the bill to accelerate the development of carbon removal technologies, including 85 percent of Democrats, 69 percent of Independents, and 59 percent of Republicans.

A key benefit of climate policy that leverages public procurement — over, for example, a compliance mechanism — is the opportunity to incorporate non-price factors into purchase decisions. Both CDRLA bills direct government entities to take into account important equity and environmental justice considerations such as benefits to disadvantaged communities, job creation, the employment of union labor, and ecosystem services. These bills demonstrate the important role the government will have not only in advancing carbon removal technologies and practices, but also the need to do so in a way that is fair and can benefit communities and ecosystems. In an era when the climate crisis threatens every aspect of society, holistic solutions like these are critical. CDR might even be a way that progressives can reach across the aisle on climate, leading the way for ambitious, wide-reaching climate legislation like those outlined in President Biden’s Build Back Better Framework.

Celina Scott-Buechler (@cescobu) is a senior resident fellow at Data for Progress.

Toby Bryce (@wtbryce) is a CDR policy advocate at OpenAir Collective.

Survey Methodology

New York State Survey: From April 7 to 13, 2022, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 622 likely voters in New York using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ±4 percentage points.

National Survey: From May 6 to 9, 2022, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1,171 likely voters nationally using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ±3 percentage points.