Gas Rules Everything Around Me

By Colin McAuliffe

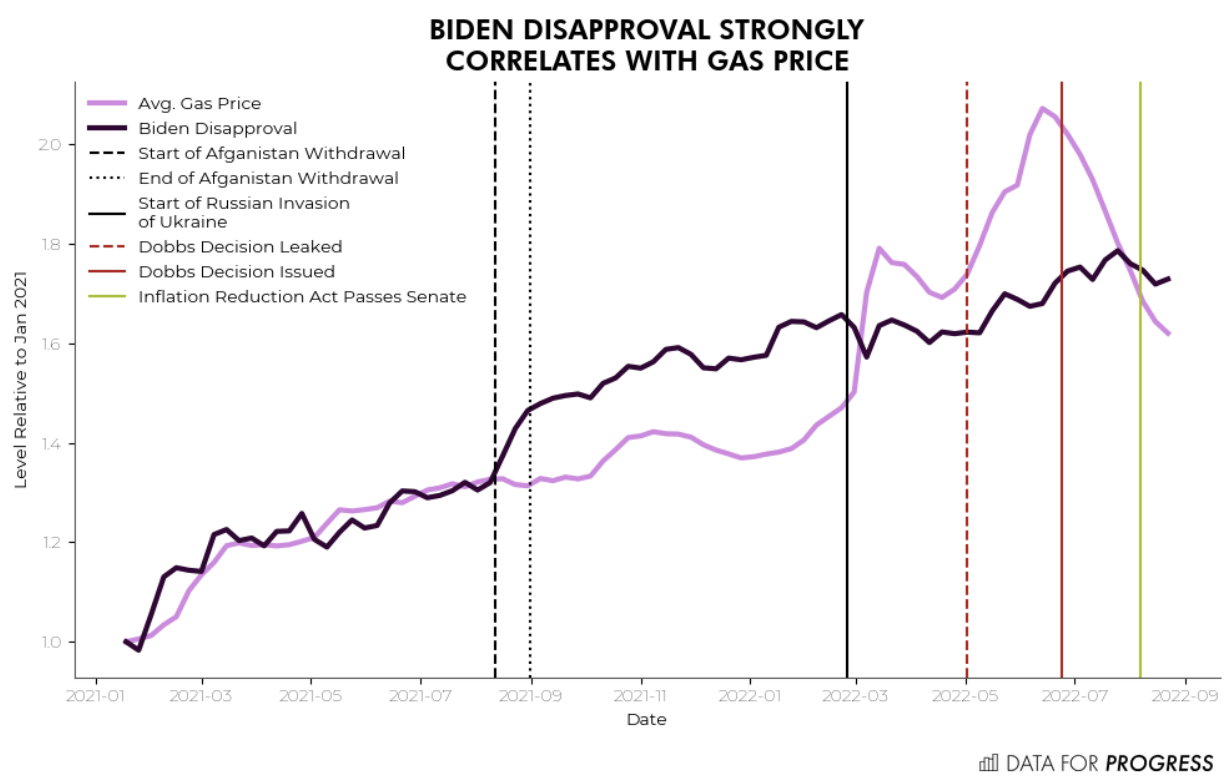

Last November, we argued that we could find little evidence that the stark declines in President Biden’s approval ratings could be attributed to voter opposition to his domestic agenda. Instead, we argued that Biden’s descending approval was being driven by the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, as well as rising prices for gas and other salient staples.

The crux of our argument was that misattributing the source of Biden’s falling ratings could cause lawmakers to get cold feet and scrap aspects of his agenda which were clearly positive — such as rapid job growth, a flurry of announcements from private businesses about capacity-expanding investments, an expanded child tax credit giving a lifeline to millions of families (which we later found was likely having a positive political effect), and signs of a tightening labor market giving workers leverage that they have not seen for decades.

Since then, several other major political events have occurred, from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, to the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, to the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. As a result, we have now updated our analysis. We find that Biden’s falling approval ratings are still highly correlated with rising gas prices.

Our original analysis was roasted on Twitter for showing a correlation between gas prices and Biden’s approval without any attempt to demonstrate causation. Even though we avoided using causal language, this is still a fair criticism since general audiences tend to interpret correlations as causal by default, so it’s generally good practice to avoid showing any correlation if you are not comfortable with it being perceived as causal. Of course, not all correlations signify causation — it’s possible that the linkage in time between gas prices and Biden approval is a completely spurious correlation where no underlying causal relationship exists. It’s even possible that linkage through time can mask a negative causal relationship — the opposite of the apparent positive correlation!

But there’s plenty of evidence that the correlation between rising gas prices and Biden’s falling approval is not just a coincidence — throughout history, when voters have faced higher prices at the pump, they have responded by directing their frustrations at the president. Historically, incumbent governments in democracies routinely faced backlash from rising prices and especially rising energy prices, ranging from higher rates of disapproval, to electoral penalties, to uprisings of varying degrees of violence. Even in autocratic countries, a common strategy to maintain stability is to appease the populace by keeping low prices for fuel and food. The current backlash from rising energy prices is also a global phenomenon, with some of the most severe political disruptions occurring in Ecuador and Kazakhstan.

It would be pretty shocking if President Biden were to become the exception to this rule. So while our analysis can not make novel causal claims about the relationship between Biden approval and gas price, when placed in historical and global context, the observed correlation does provide us with actionable information. However, we discussed a more important limitation of our analysis last winter, which is that we are using gas price as a rough proxy for a whole basket of goods including energy prices more broadly as well as food, whose prices are highly politically salient but are much less prominent in economists’ favored inflation indexes. Creating a price index covering this whole basket of goods is a fascinating question, but for now, gas price will do since it is likely to be the most important item in the basket.

Furthermore, with nine months of new data since our original post, we continue to see a clear correlation between rising gas prices and Biden’s declining approval. Between the time of our original post and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we see gas prices and Biden disapproval continue to move in tandem until the beginning of the invasion, where they temporarily diverge.

The Russian invasion caused a substantial and rapid shock to gas prices, while Biden’s rates of disapproval stayed roughly stable. If it were possible to argue that the invasion had no influence on Biden’s approval independent of its effect on gas prices, we would have an opportunity to pull correlation apart from causation in an empirically sound way. However, it’s very likely that the Russian invasion of Ukraine had an effect on Biden’s approval independent of its effect on gas prices, because major geopolitical events typically influence presidential approval directly. We even see Biden’s disapproval tick down a bit immediately after the invasion before stabilizing briefly and finally giving way as gas prices continue to climb. Biden faced relentless media criticism during the Afghanistan withdrawal that was not present to the same degree at the start of the invasion. It’s also possible that voters’ belief that the price rises would quickly pass helped temporarily prevent Biden’s approval from sliding. This appears to be a common pattern with approval of western governments in Europe — for example, French President Emmanuel Macron seems to have enjoyed a small and fleeting bump in polling over rival far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen immediately following the invasion, which quickly collapsed as energy prices rose.

Later in the year, after the Dobbs decision to overturn Roe v. Wade was issued, we see Biden’s approval begin to improve. While the Dobbs decision is itself unrelated to gas price, in a bizarre matter of chance, gas prices seem to have peaked mere days before the Dobbs decision was formally issued. Subsequently, as gas prices have fallen, we have seen a rise in Biden’s approval, as well as two special elections in which Democrats have overperformed — two pieces of evidence that Democrats’ midterm prospects have improved compared to last spring. While it is still early, we have not seen any popular mobilization against the landmark Inflation Reduction Act as there was against the Affordable Care Act. If it were true that Biden’s approval numbers are a consequence of an unpopular domestic agenda as opposed to rising prices, we would expect to see some kind of backlash to the passage of the IRA, but there doesn’t appear to be any yet.

The takeaway is clear: Biden’s struggles with voter approval have been mostly unrelated to his actual domestic policy agenda.

Countless center-left governments have seen their agendas undermined by political backlash to rising prices. These same governments also rightly viewed the standard tool to fight inflation — a central bank intervening to reduce demand by tightening financial conditions and ultimately reducing workers’ incomes and bargaining power — as antithetical to their goals and values, but the issue of inflation remains nonetheless. Their viewpoint is that if owners of capital have failed to deploy their resources to create supply that is sufficient for price stability, we should not respond by forcing workers and poor people to reduce their consumption by enacting policies to reduce their income. Aside from the inequity of this response, these same policy responses simultaneously risk choking off the investments needed to ensure adequate future supply.

Instead, center-left governments have used a wide array of alternative policies to prevent inflation and the resulting central bank tightening before it happens, such as active labor market policy, ensuring abundant housing to allow for the worker mobility needed to sustain a hot economy, sector-level collective bargaining, direct public investment, and industrial policy to shape private investment. In other words, price stability must be a top priority, but if we are going to take increasing unemployment off the table as a policy response, we need another set of tools. There are many different policies that could fit under this very broad umbrella, but it is worth noting that the Biden administration has already adopted some policies designed to stabilize prices over the long run in some sectors. Our analysis shows that Biden’s break with the status quo is the right call — not only because his policies help American workers and families, but because they are politically sound — they do not appear to be responsible for the president’s decline in approval.

However, as history shows, trying to control inflation without increasing unemployment requires implementing a complex set of complementary anti-inflation policies, which often require institutional frameworks that the U.S. currently lacks. This presents a major political challenge, especially in the modern environment where narrow majorities are commonplace. There is no question that it is politically much easier to simply stand by while the Federal Reserve tightens financial conditions and increases unemployment in accordance with their mandate, since the costs of these decisions are allocated in a way that tends to have lower political salience than the legislative agenda of the party in power. But these costs are very high, and so it’s a fight worth taking on. There are clearly no easy solutions here as we walk a tightrope between facing backlash from rising prices and fighting through the inertia of the lawmaking process, but it is important not to conflate short-term blowback against rising prices with blowback against an agenda which has many aspects that set the table for long-run price stability.

These challenges are not just some historical anomaly and will likely become even more relevant as efforts to transition to a carbon-free economy intensify. Energy price stability means political stability, and energy price stability on a warming planet requires investments in an abundance of renewable energy far beyond what the free market is willing to provide. While it is unclear what effect they will have on energy prices in the immediate term as November approaches, the targeted investments of the Inflation Reduction Act are a welcome step towards an energy transition that prioritizes stable energy prices — which could ultimately mean more stable presidential approval. We hope to see this model taken further in future legislation.

Colin McAuliffe (@ColinJMcAuliffe) is a Co-founder of Data for Progress