How to Actually Build Things - A Response to Marc Andreeson

By Colin Mcaullife and Jason Ganz

Earlier this month, famed venture capitalist Marc Andreeson published a blog entitled “It’s Time to Build Things”.

This post got a ton of shares and a ton of traction among the usual Silicon Valley tech cultists and weirdos, but it also got read and shared by many smart, talented people who felt in it something real. While most people would probably be better off being alive today than any other time in the past, Marc clearly recognizes that society is not living up to its potential, and we agree. As we have all watched the senseless levels of suffering endured by many people under the stagnation and decline of our economies, our cities and our communities over the past several decades, many of us have a deep understanding that there has to be a better way.

Because we are in a time that calls us desperately, urgently to build new things, to bring to life the world which is struggling to be born. We have ten years to dramatically reduce our carbon emissions to avert climate catastrophe. We live in the richest country in the history of the world, but we cannot produce enough cotton swabs to ensure proper testing in the middle of a pandemic. And also in that richest country in the world we’re painting lines in parking lots to ensure homeless people practice social distancing rather than putting them in the thousands of empty hotel rooms.

It is impossible to see all this and not feel, deeply, that we are failing as a society.

Source: Steve Marcus/Reuters

So we must concede that Marc raises an interesting point. Or rather, Marc raises one third of an interesting point because realizing that we need to build things leads to three other, far more difficult problems.

If we haven’t been building, what have we been doing instead?

Why haven’t we been building things already?

What do we build now?

These questions, it turns out are extremely interesting. The answer to why we aren’t building requires a deeper understanding of how progress is made, both on a technical and a societal level. And once that understanding is achieved it becomes obvious what we need to build.

Our answers to these questions are:

Instead of building a society that prioritizes human flourishing, we have built a society where the accumulation of money by private property owners is placed above all else.

These badly skewed priorities have not only hampered what can be built, but completely block us from building even simple and obviously useful things.

Since ultimately the problem is about who holds power, the only way to challenge this is through building political power.

Marc would like you to believe that the answer to our current problems is for society, collectively to pull itself up by its bootstraps and simply choose to build instead of choosing to not build.

“The problem is desire. We need to *want* these things. The problem is inertia. We need to want these things more than we want to prevent these things. The problem is regulatory capture. We need to want new companies to build these things, even if incumbents don’t like it, even if only to force the incumbents to build these things. And the problem is will. We need to build these things.”

The belief that a dramatic change in outcomes can be attributed to a simple change in desire is simplistic and reductive to apply to an individual. On a national scale it's simply farcical. This is the societal equivalent of telling the country to take online classes at Udacity while working two full time jobs and raising a family in order to improve their career prospects.

To be fair to Marc, he does take his analysis one step further, but only to smugly tell us that the problem can’t be political, writing:

“Many of us would like to pin the cause on one political party or another, on one government or another. But the harsh reality is that it all failed — no Western country, or state, or city was prepared — and despite hard work and often extraordinary sacrifice by many people within these institutions. So the problem runs deeper than your favorite political opponent or your home nation.”

Marc’s point here is again narrowly true in that the national outcomes are broadly similar across Western economies and that any given election won’t change that. But he again misses the larger point as he is only able to visualize the narrow range of political outcomes which are considered possible under the dominant operating framework that has taken hold over the past fifty years. Every country Marc is thinking of has been subject to austerity, financial liberalization and the hollowing out of the public sector.

Every country has systematically underinvested in the social programs, the fundamental research and the large scale projects that would be necessary to provide the groundwork truly needed to build the world that Marc envisions.

One must actually empathize with Marc a bit here. Without the ability to look beyond current governmental and financial frameworks, it must be a truly frustrating and seemingly unknowable problem. After all, the tech utopian project he has dedicated his life to has utterly failed to solve the real, big problems of the world.

For all the accelerators, the maker spaces, the 10X projects and moonshots, it seems like what we get are only a few (arguably) major contributions from the world of tech to fighting the pandemic, mainly cheap and accessible long distance digital communications.

And Marc does seem to despair at this.

“Why do we not have these things? Medical equipment and financial conduits involve no rocket science whatsoever. At least therapies and vaccines are hard! Making masks and transferring money are not hard. We could have these things but we chose not to — specifically we chose not to have the mechanisms, the factories, the systems to make these things. We chose not to *build*.”

We chose not to build the financial conduits to get assistance to normal people, yet we have nearly unlimited money for the banks and the people who put us in this situation in the first place. What we are seeing is not a system that’s failing, it's one that is protecting the people it is designed to protect.

Because a global system based off the private market, the sanctity of profit and endless disdain for the poor, the disabled, the “unskilled” (but essential) laborers was always leading here.

It seems Marc knows that his analysis falls short, since he goes so far as to address his critics in a totally normal and not defensive way writing:

“I expect this essay to be the target of criticism. Here’s a modest proposal to my critics. Instead of attacking my ideas of what to build, conceive your own! What do you think we should build? There’s an excellent chance I’ll agree with you.”

We’ll be happy to oblige, and at the end of this essay we will discuss what we would like to build. But before we do, we think it’s worthwhile to explore some of the points Marc raised at length.

Why don’t we build more schools, more hospitals, and more homes?

Marc opines that we don’t build enough housing, schools, and hospitals, pointing to a lack of desire and complacency with the status quo. As Vicki Boykis points out, this entire frame is preposterous, since most individuals lack the resources or the time to build their own Singapore skyline. In a country where 20% of children are forced to endure poverty, many families lack the resources to buy food and pay rent, and building a hospital is pretty much out of the question.

This framing also misses the point that many of us do not build for ourselves because capitalism demands that our time be spent building for someone else. We do not build for ourselves because we are otherwise occupied working, traveling to or from work, preparing for work, and recovering from work. We do not build for ourselves because we are caring for the next generation of workers, or for the last generation of workers who can no longer work. Many others do not build for no reason other than that they were born into circumstances where their potential could not be realized.

But despite the wrong frame, Marc once again approaches the right answer with this passage

In fact, I think building is how we reboot the American dream. The things we build in huge quantities, like computers and TVs, drop rapidly in price. The things we don’t, like housing, schools, and hospitals, skyrocket in price. What’s the American dream? The opportunity to have a home of your own, and a family you can provide for. We need to break the rapidly escalating price curves for housing, education, and healthcare, to make sure that every American can realize the dream, and the only way to do that is to build.

Here is economist John Kenneth Galbraith, from his 1958 book The Affluent Society, appearing to answer Marc directly

The relation of the sales tax to the problem of social balance is admirably direct. The community is affluent in privately produced goods. It is poor in public services. The obvious solution is to tax the former to provide the latter - by making private goods more expensive, public goods are made more abundant. Motion pictures, electronic entertainment and cigarettes are made more costly so that schools can be more handsomely supported. We pay more for soap, detergents and vacuum cleaners in order that we may have a cleaner urban environment and less occasion to use them. We have more expensive cars and gasoline so that we may have more agreeable highways and streets on which to drive them. Food being relatively cheap, we tax it in order to have better medical services and better health in which to enjoy it.

Galbraith mentions sales tax specifically, but the general concept is that we transfer resources from areas where markets are more or less functional to areas where markets do not work well, or where market allocation can not meet higher goals such as equity and universality of provision. That is, we can transfer resources from sectors where we build in “huge quantities”, so that we can provide everyone with a home, with healthcare, and with education. In turn, this produces a workforce that is housed, healthy, and equipped with the skills that are needed to build “huge quantities” of things in the first place.

Marc calls for us to prove this model, but the efficacy of this model has already been proven, every rich country has figured this out to some extent. Additionally, the experience of the US proves the negative consequences of the private model. For example, the refusal to use public spending in the healthcare system has been a driver not just in failure to build new hospitals, but in closures of existing hospitals as well.

The broader concept underpinning this public model is in fact conventional wisdom in the business world. Firms recognize that not all of their products and services should be profit maximizing individually, and that some can even lose money as long as they complement other goods and services in a way that maximizes firm profits as a whole. Similarly, we should recognize that not all parts of the economy need to be profit centers, and instead we should design the economy to create the most well-being for the most people possible.

This kind of cross industry transfer is critical for responding to pandemics like covid, and there is no private substitute. Pandemics require rapidly scaling up health sector capacity, which means one of two things. Either we let resources sit idle during normal times, so they are available to use at a moment’s notice during an emergency, or we scale up capacity by drawing resources away from parts of the economy where they were employed for other uses pre crisis. The only precedent for anything of this scale is state directed economic planning during times of war, and there is no market model that could accomplish the same rapid transitions in production. Meanwhile, the lack of a coordinated public response to the coronavirus has not led to spontaneous and coherent private response. Instead, state governments are scrambling to hack together an impromptu federal government to deal with the chaos created by the lack of central coordination.

But the question remains: why has the US refused to use public resources for the benefit of the public? The answer is again a matter of political power. The ruling class has made the conscious choice that every aspect of life should be a site for profit extraction, and that the public sector exists primarily to create and maintain the conditions that allow extraction to occur. While some refer to this as “unfettered capitalism”, the truth is that capitalism is itself a system of fetters that are placed on society to allow private property owners to accumulate money by taking it from the productive parts of the economy.

This is why we have ostensible social insurance programs that are designed to humiliate people who are struggling and force them to jump through hoops or else be denied their benefit. The government lacks the infrastructure to send checks to individuals, but it possesses the infrastructure to shore up the finances of banks and large corporations at the snap of a finger. State capacity exists in abundance, but it is deployed for the benefit of a small number of private property owners, not for society as a whole. The idea that this state of affairs represents a lack of desire on the part of ordinary people and not an immoral and unjustified set of priorities on the part of the small number of people in the country who are capable of setting policy is manifestly untrue.

Why don’t we automate?

Marc wonders why we do not have highly automated factories such as those imagined by Elon Musk. The answer again is one of power. The variant of capitalism that has existed in the US since the 80s is designed to suppress wage growth and to inflate the values of assets. Aside from transferring wealth from workers to property owners among other effects, this systematically removes some of the incentives for innovations that leads to real productivity growth, while incentivizing practices that only seek to gobble up as much of the existing share of economic output as possible, without actually creating anything new.

The empirical results to this effect are quite striking, but the dynamics can be understood in much simpler terms. If a firm is not under pressure to keep prices low in the face of rising labor costs, what incentive do they have to invest in new and potentially expensive labor saving technology? If a firm can reduce labor costs through various workplace fissuring and worker misclassification strategies, why should they bother with automation at all?

Many firms have found that automating low wage labor is much too difficult, while automating managerial tasks to surveil and prod low wage workers to wring out as much productivity as possible from them is easier. Capitalists have decided that building a legal and technical apparatus that allows them to crush their workers is a better path to profits than building machines which perform complex tasks, so the machines do not get built. If Marc is upset about this, he should support the growing unionization efforts and labor struggles around the country, or to demand that the broken unemployment system he derides be fixed.

We also don’t automate because we have entrusted the private sector with roles in the innovation process which it is structurally incapable of fulfilling. Innovation is a buzzword that is thrown around quite a bit, and it’s meaning is often intended to be vague. We should understand innovation to consist of all aspects of the process of discovering new knowledge about the world, and turning this knowledge into a system or product that serves some particular purpose. The process is not linear. It is constantly pausing and restarting as it moves forward, as the new knowledge learned from failures and successes gradually percolates out from where it originated.

If we only measured the success of innovation in terms of revenues exceeding costs, we would never innovate. There is no guarantee that an investigation to try to learn something new about how the world works will be successful. But if there was, there is no guarantee that this new knowledge could be successfully incorporated into a system involving physical components and/or software. But if there was, there is no guarantee that such a system could actually be produced and deployed in their real world. But if there was, there is no guarantee that such a product would be profitable. But if there was, there is no guarantee that such a product would have much meaningful societal value.

When he was developing it, Einstein’s theory of relativity probably would have sounded like science fiction, or at best some esoteric nonsense to most businesspeople. Yet today, satellite communication systems, which also underpin so much other technology that society runs on, would not work without it. Who in Einstein’s day would have predicted that relativity would one day lead to a market for selling devices that you keep in your personal automobile which communicate with objects orbiting the earth to give you directions? Probably no one.

Innovation is often associated with “visionary” leaders, but the truth is that most of the future benefits of a discovery are completely unforeseeable, while the present costs of failing are very high. This means that any outfit that is constrained to make a profit will not be very good at most parts of the innovation process. They will also have strong incentives to use the legal system to actively block new ideas from being used by others, regardless of whether or not those other outfits are capable of putting those ideas to more productive use.

Marc runs a venture capital fund, and VCs are well known for taking on investments with much higher risk profiles than other types of investors. But in the grand scheme of things, you could combine every VC fund in the world and it is still small potatoes compared to the resources needed to sustain the entire innovation process.

We can clearly see poor outcomes resulting from the private sector attempts at automating tasks which they are not equipped to automate. Despite years of lofty promises, self driving cars are nowhere close to achieving human-levels of proficiency, and the rate of progress has all but ground to a halt. Further, failures to achieve high levels of autonomy in personal vehicles is likely a canary in the coal mine, signaling that a much larger bubble of projects that rely on the promise of rapid advances in a field called supervised machine learning is about to burst.

Since scientific progress is unpredictable, trying things and failing is important. But many of the failures that we are seeing in autonomy today are largely predictable, based on the knowledge learned from past automation efforts which were successful. Even worse, it’s not clear that the industry is actually learning from their failures. While some firms are quietly revising their expectations, others are coping with the inability to achieve full autonomy by replacing human drivers with….wait for it….remote control human drivers.

For anyone with a technical background, decisions like this appear completely nonsensical. Fully removing a human operator from a vehicle already comes with tradeoffs because human operators perform a number of tasks that are not related to driving the vehicle. This includes providing assistance for passengers who need help boarding and exiting the vehicle, providing directions, and being responsible for contacting the police or medical services in an emergency. The fact that some companies appear to be willing to forgo the advantages of human operated vehicles when they can not even deliver full autonomy suggests that the incentive structures in the industry are badly broken.

We can do a lot better than this. It starts by recognizing that the role for the private sector in the innovation process is to commercialize technologies that have already achieved a high level of technological maturity, not to try to undertake moonshots. After all, if a firm feels comfortable taking a high risk play that may not pay off for years (or which may not pay off at all without first successfully cornering a market), then that firm is probably too comfortable. Rising labor costs and competition from other firms should be disincentivizing firms from these high risk moonshots, and forcing them to tweak production in smaller but more surefire ways to increase their productivity immediately to remain competitive.

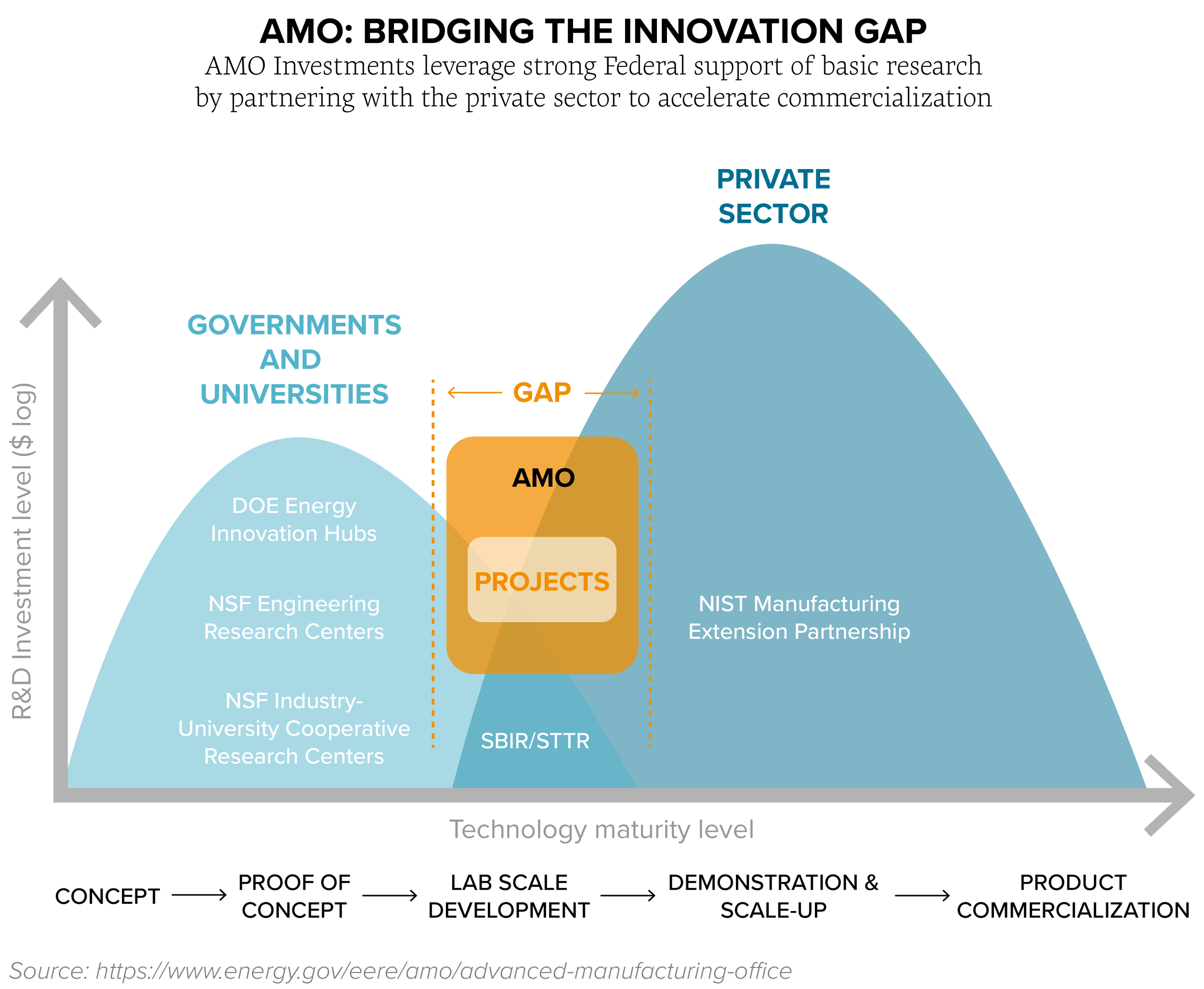

We have to recognize the role that public investment in innovation both historically and presently, which has been documented extensively by left leaning economist Mariana Muzzacato. It has also been well documented by the not so left leaning consultancy Deloitte for the specific case of US manufacturing, which Marc notes has managed record output. As this sketch from a Department of Energy program illustrates, public resources are used to socialize the costs of early technological development. Public resources are further used to socialize the costs of the transition to commercialization by the private sector, which is a critical phase in the innovation process where many promising ideas ultimately fail.

Acknowledging the role of public investment in innovation leads to two important conclusions. The first is that we should do a lot more of it, perhaps by as much as 3-4% of GDP per year. Contrary to narratives about public spending “crowding out” private investments, there is good reason to believe that public R&D actually “crowds in” private R&D. One paper estimated that a 10% increase in public R&D spending would induce an additional 4.3% in private R&D spending. A large expansion in public R&D would also create millions of jobs, and not just for those who are highly educated. Research facilities can sustain vibrant communities with opportunities available to people from all walks of life.

The second conclusion is that once we recognize that innovation in modern economies requires that we socialize much of the associated costs and risks, then we also must ensure that the benefits that come from projects that are ultimately successful are broadly shared. This should be accomplished both in financial terms, by using a portion of the profits generated by successful projects on social spending, as well as in nonfinancial terms, by prioritizing development of technology with high societal value.

Again we need not prove the efficacy of this model, because it has already been proven in the US and elsewhere. What we need is the political power to reclaim the public R&D apparatus for the benefit of the public, while now it is primarily employed to transfer public wealth to the shareholders of large corporations, and to equip Gulf dictatorships with high tech weaponry that they use for precision targeted bombings of schools and hospitals.

Marc has more influence than the average person, and he could use this influence to advocate for a reality-based approach to innovation if he wanted. Under such a system, the Marcs of the world would still have a role to play in the innovation process. They would still live very comfortably and find themselves inundated with new opportunities to build.

However, it’s not likely that society would confer him the same social prestige that it does now. Once we understand how innovation actually works, it’s hard to view VCs as far-sighted visionaries who are fundamentally revolutionizing the world. Instead, we would see them as quasi-independent civil servants, who are performing the final few tasks to bring the culmination of decades of public investment across the finish line. We trust that Marc is as committed to building as he says he is, and that he would be eager to fill this role.

What are we building?

As promised, we will finally answer Marc’s question “what are you building?” We have quite a few ideas on what we could build, but none of this matters if we first do not build the power to implement them. The Data for Progress mission is to build the infrastructure within the political system that will be required to sustain a durable progressive movement. We view one of our main roles to be to show the media and politicians that the public enthusiastically supports a number of left wing ideas that would directly tackle many of the problems that we face, including many problems that Marc claims that he wants to see solved.

We believe that there are substantial gains to be won inside the sphere of electoral politics and policy with this approach. But participation in electoral politics is a privilege in many respects, and since it is our job to find where the limits of electoral politics lie, we are acutely aware of the fact that electoral politics alone is not sufficient to build the power needed to challenge the forces who believe that the only things worth building are things that the wealthy can take profits from.

So build by building power for working people in all aspects of your life. Build by organizing your workplace. Build by organizing your neighbors against abusive landlords. Built by fighting for affordable housing within your community. Build by joining your local chapter of DSA, of Indivisible, of the Tech Workers Coalition. Build by rejecting Marc’s fascist friends, who seek to profit by undermining democracy worldwide. Build by refusing to build the tools that Marc’s fascist friends use to brutalize our fellow human beings.

Build by offering your time to help those attempting to cope with the systems capitalism has built to frustrate and humiliate them. Build by connecting people subject to eviction or debt collection with competent and free legal counsel. Build by donating to abortion access funds. Build by registering your friends to vote. Build by helping your neighbors navigate the unemployment system, healthcare system, and tax systems which have been built to cheat working people out of their benefits. Build by showing people that the many daily indignities that poor and working people are subjected to can be fought and beaten through collective struggle. Build by rebuilding the social trust that has eroded after decades of rule under a system that values profits over human flourishing.