Voters Have Mixed Opinions About America’s Party System

By Ethan Winter

Edited by Andrew Mangan, Senior Editor, Data for Progress

The rise of the Tea Party and President Trump’s unexpected victory in 2016 prompted commentators to reconsider the relationship between political parties and American democracy. Throughout this, repeat reference to a 1950 report by Committee on Political Parties (CPP) of the American Political Science Association titled “Toward a More Responsible Two-party System.” Only ninety-nine pages long and written in relatively dry prose, the report proposed a series of reforms to the two major parties. The CPP operated with a specific vision of how the party system was to operate. Their end goal was the creation of two disciplined parties, i.e., capable of partisan coordination, that would be modestly differentiated, with one party being “liberal” and the other “conservative.” In addition and quite crucially, the parties would contest new kinds of national issues, in so doing eroding existing one-party systems that persisted at the sub-national level in the United States well into the mid-twentieth century.

For a rather dry document—the report avoids, for the most part, direct confrontation with the contentious policy issues of civil rights and the Cold War, focusing instead on the internal organization of the two major parties—it remains an object of considerable interest. As part of a May 2020 survey, Data for Progress tested registered voters’ attitudes on America’s system of political parties in the hope of gauging their attitudes towards the broad goals of the CPP.

To do this, we tested for questions. First, we asked voters about how important they thought it was that members of the same party agree with one another, using a four-point scale: “very important,” “somewhat important,” “a little important,” “not at all important.” Ideological unity among co-partisans is important for two major reasons. First, collective action is required to pass legislation. For example, to pass a bill that would increase access to abortion, party members must agree that, at least in principle, this is a worthy goal. Second, ideological unity among co-partisans ensures that when voters cast their ballot for a member of one party, they’re empowering a political party in line with their goals. As the writer Eric Levitz notes, the “utter dearth of partisan polarization undermined democratic accountability. A liberal could vote for Democratic candidates in New York, and unwittingly empower arch-segregationists in the Senate.

Overall, we found that most voters thought it was important that members of the same party agree with one another, though attitudes were muted. Just under a third of voters (29 percent) said that it was “very important,” while 45 percent—a clear plurality—said that it was “somewhat important.” The remaining 27 percent of voters said that it was “a little important” or “not at all important.” Responses were consistent across partisanship.

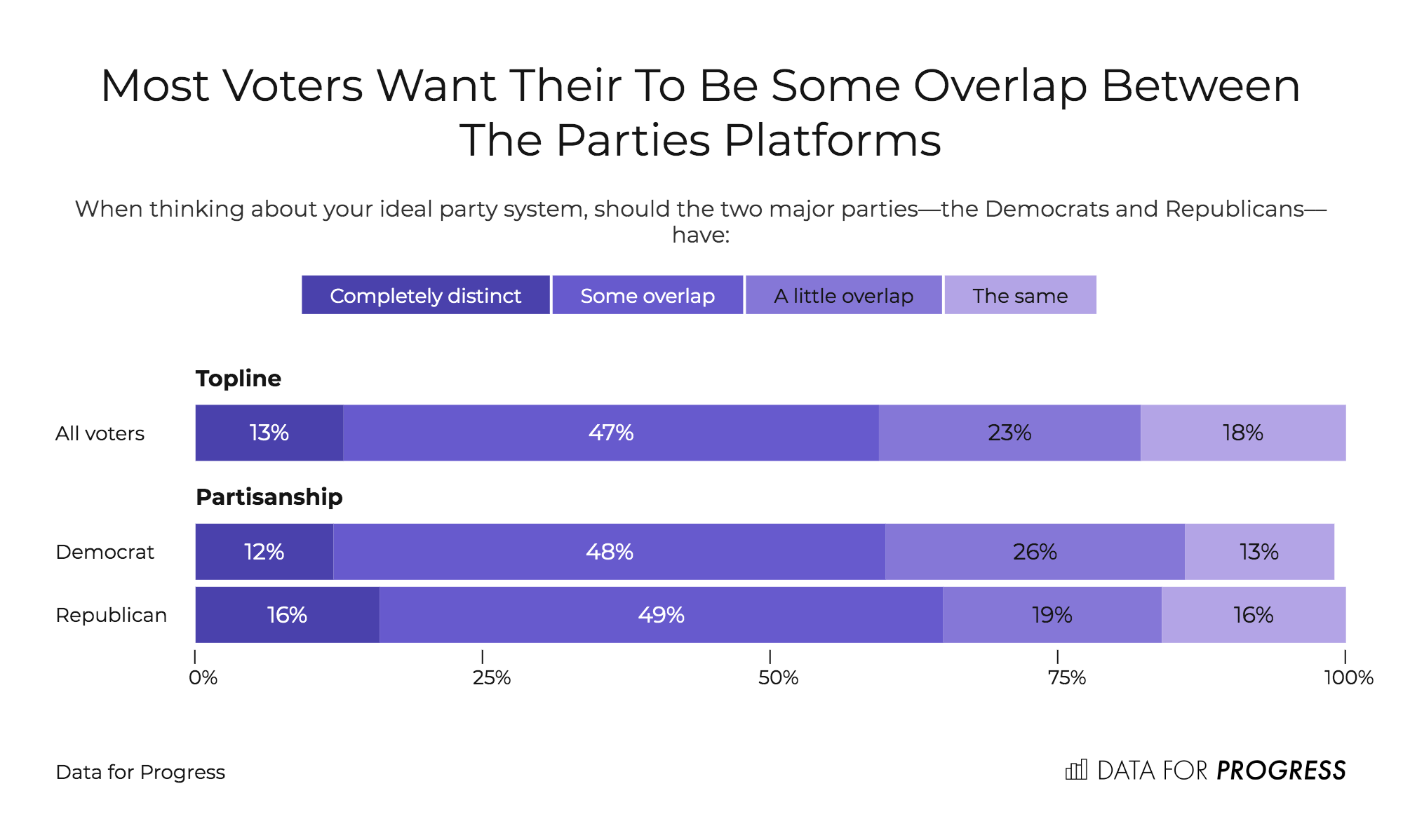

Next, we asked voters how important it was to them that the two major parties have different policy platforms. Voters were then provided a four-point scale by which to register their responses: “Completely distinct policy platforms, “Some overlap in their policy platforms,” “A little overlap in their policy platforms,” “They should have the same policy platforms.”

This question attempts to understand how important “choice” is to voters. In America’s two-party system, voters have two feasible options at the ballot box—the Democratic candidate or the Republican candidate—but there still exists a range for how different these options should be. This provides a roundabout way of probing voters’ attitudes toward the country’s present partisan polarization. Specifically, do voters want this current state of affairs to intensify—i.e., have the parties move further apart in the policy space—or do they want depolarization—i.e., have the parties been drawn closer together?

We found a near-majority (47 percent) of voters want there to be “some overlap” between the policy platforms of the two major parties. Meanwhile, 13 percent want the platforms to be “completely distinct.” Twenty-three percent was “a little overlap” between the platforms, and 18 percent of voters want the platforms to be “the same.” Again, attitudes were generally consistent regardless of partisanship.

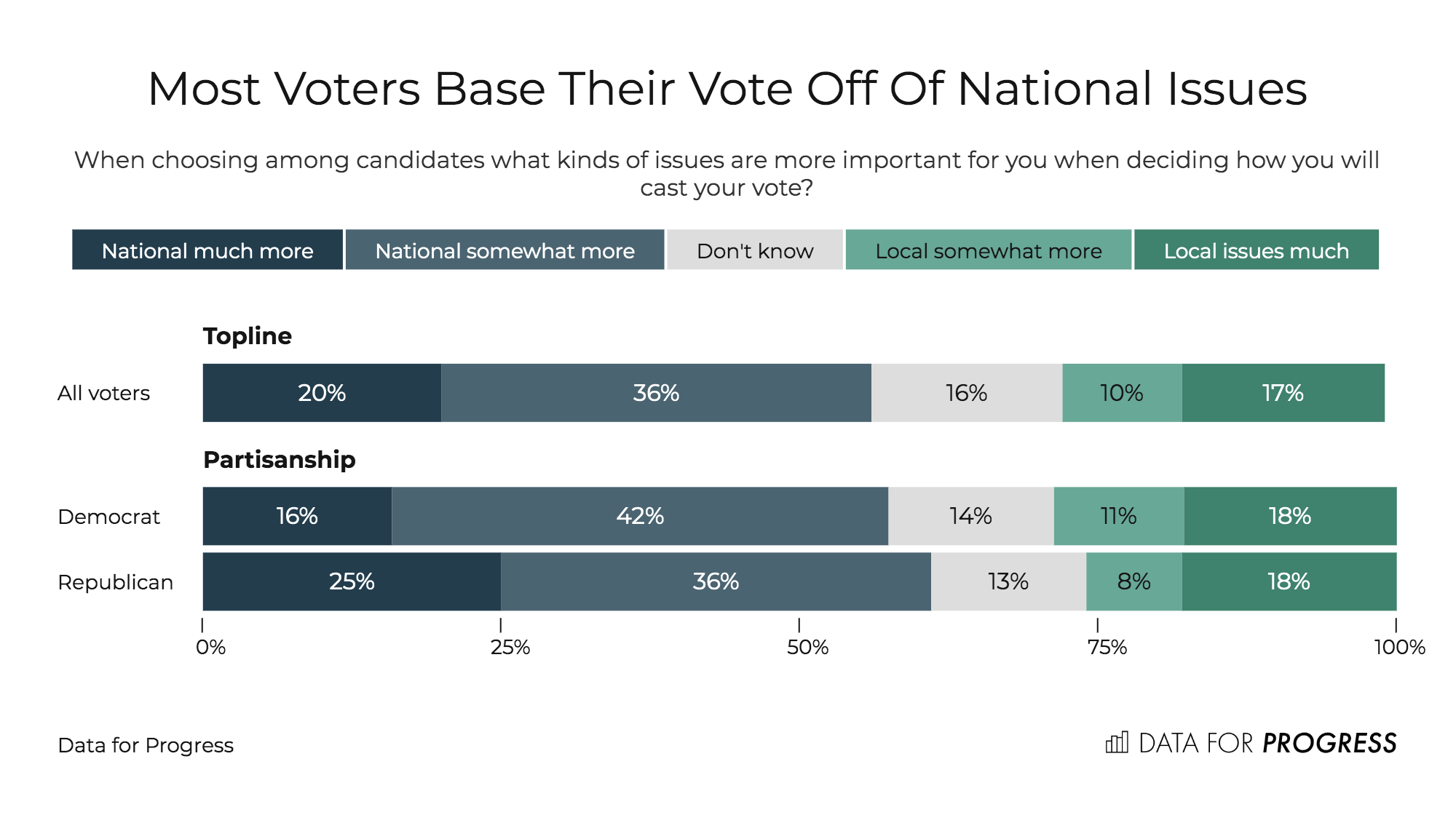

In the next question, we asked voters about whether they weigh national or local issues more heavily when deciding on a candidate to vote for. Voters were provided a five-point scale, ranging from “National issues are much more important than local issues” to “Local issues are much more important than national issues,” with a fifth option of “Don’t know / Not sure” available.

A majority of voters (56 percent) reported that national issues matter more to them than local issues when deciding whom to vote for, compared to 27 percent of voters for whom local issues matter more. The remaining 16 percent weren’t sure.

There is a clear policy rationale for this kind of voting behavior. After the New Deal, the federal government had to deal with two new kinds of policy—regulatory policy and redistributive policy—which, by design, created a zero-sum political competition. This revolutionized the role of the federal government, which had thus far dealt predominantly with distributive policies. In the ninety years since the New Deal, national policy issues have only grown in importance for voters. And the media’s increased reach through broadcast news and then the internet has only added fuel to this fire.

There are some who fret about the nationalization of politics––a trend that Yascha Mounk calls in a rather canned turn of phrase, “the rise of McPolitics”––and see in a re-energized local politics a strategy for depolarizing the nation’s parties. Yet this finding, that voters tend to cast their vote based on national issues, raises doubts about the feasibility––to say nothing of its actual desirability––of such a strategy. In truth, there simply are national issues that confront the American electorate and people vote accordingly.

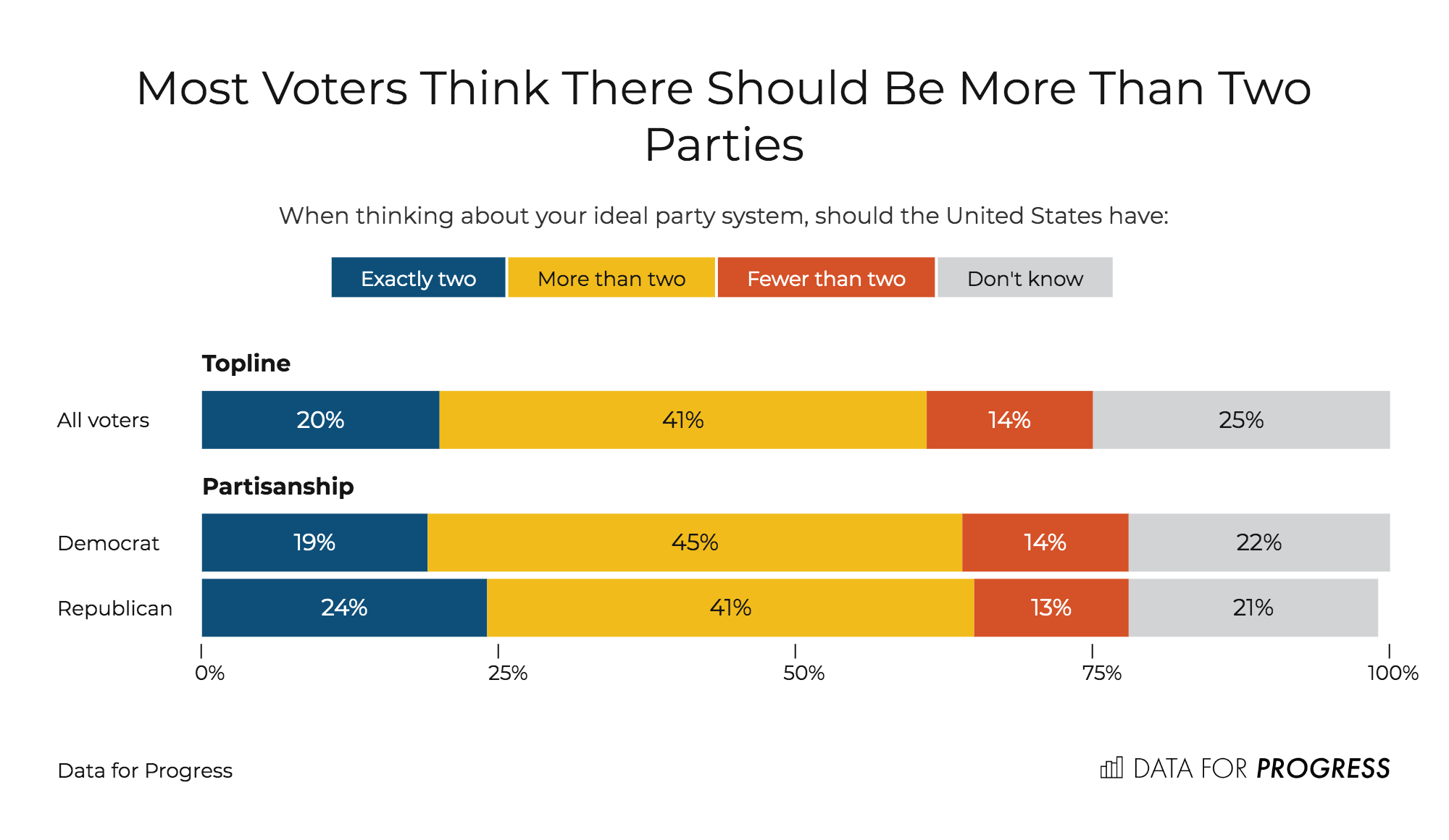

The last question we asked voters was about how many parties they envisioned in their ideal party-based system. Voters were provided four response options: “Exactly two political parties,” “More than two political parties,” “Fewer than two political parties,” “Don’t know / Not sure.”

America’s two-party system is one of the country’s most prominent political ordering mechanisms. Though American political culture venerates popular sovereignty, American voters have (for the most part) two practical choices at the ballot box. As the political scientist E. E. Schattschneider put it: “The people are a sovereign whose vocabulary is limited to two words, ‘Yes’ or ‘No.’”

In our survey we found that most voters do not prefer this two-party arrangement. A plurality (41 percent) of voters think there should be more than two parties. Only 20 percent think there should be exactly two parties, while 14 percent said there should be fewer than two parties, with the remaining 25 percent reporting that they weren’t sure.

This finding is somewhat discordant with the apparent increase in partisanship. Both Democrats and Republicans want an alternative to the status quo. What they want this alternative to be isn’t clear, however. There are some who try to offer a socially liberal and fiscally conservative option. Yet, this hasn’t entirely taken off. Last year, Howard Schultz, former CEO of Starbucks, briefly entertained a presidential bid, positioning himself as fiscally conservative and socially liberal, only to be ratio’d out of the race. There’s not much of a constituency for that kind of politics.

Survey data does show, though, that there is a fairly large slice of voters who are the inverse of Schultz: fiscally liberal and socially conservative. If there were to be a successful, national third party in the United States—say, like the Populist or People’s Parties of the 1880s–90s—it would likely occupy this electoral space. Yet, restrictive ballot access laws largely preclude such an eventuality. 2020, for instance, will likely see minor parties’ share of the vote fall as they struggle to get onto the ballot owing to the public health emergency. While America’s system of electoral duopoly––i.e., a complex set of rules put in place by the two major parties to secure their dominant position within the political system––is a relatively recent one, a creation only of the twentieth century, it’s likely a durable political formation.

Many have argued that partisan conflict is eroding the base of American democracy. However, if a democratic egalitarianism is one’s true goal, the convergence of the two political parties on some midpoint won’t advance this cause. (To build a more perfect union, there’s a case to be made that we aren’t polarized enough.) Instead, an intensified conflict between the two parties provides a means of constructing a more democratic society.

Authorship & Methodology

Ethan Winter (@EthanBWinter) is an analyst at Data for Progress. You can email him at ethan [at] dataforprogress [dot] org.

From May 8 through May 9, 2020, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1,235 likely voters nationally using web-panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, urbanicity, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ± 2.8 percentage points.

Due to rounding, some values sum to 99 or 101 percentage points.

Question Wording

When thinking about your ideal party system, is it important that members of the same party agree with one another on major policy issues?

1 - Very important

2 - Somewhat important

3 - A little important

4 - Not at all important

When thinking about your ideal party system, should the two major parties––the Democrats and Republicans––have:

1 - Completely distinct policy platforms

2 - Some overlap in their policy platforms

3 - A little overlap in their policy platforms.

4 - They should have the same policy platforms

When choosing among candidates what kinds of issues are more important for you when deciding how you will cast your vote?

1 - National issues are much more important than local issues

2 - National issues are somewhat more important than local issues

3 - Local issues are much more important than national issues

4 - Local issues are somewhat more important than national issues

5 - Don’t know / Not sure

When thinking about your ideal party system, should the United States have:

1 - Exactly two political parties

2 - More than two political parties

3 - Fewer than two political parties

4 - Don’t know / Not sure