In the 2020 Presidential Primary, candidates have taken increasingly progressive stances on many aspects of the criminal justice system, including growing calls to end our unjust money bail system.

Here, we compare these policies to our ideal policy, the End Money Bail Act, progressive and common sense legislation designed to dismantle America’s destructive money bail system.

The bill would encourage state and local governments to replace unjust and discriminatory money bail systems with more equitable pretrial release programs, while creating mechanisms for robust data collection to make sure these new systems are both fair and effective. The bill represents the most robust, equitable, and evidence-based approach to systemic pretrial reform at the local level.

What is Money Bail and Why Does it Matter?

Money bail is money or property that a person charged with a crime must pay to be released from jail pending trial. Wealthy people charged with crimes are able to post bail and go home, while the average person is often unable to afford money bonds and must remain in jail until the case is resolved.

None of the people held on money bail have been convicted of a crime--rather, they are all held in jail simply because they cannot afford to buy their release. And money bail affects hundreds of thousands of people every year; of the more than 700,000 people held in jails every day, 60% of those people are pending trial, meaning they have not been convicted of anything. Although some of those people have been held to protect public safety, many of those people would be released if they had the money to pay their bail.

Money bail deepens inequality. The continued use of unjust money bail policies contributes to the overall incarceration of people struggling to make ends meet and disproportionately harms people of color by keeping them locked up simply because they cannot afford to pay bail. Meanwhile, commercial bail bondsmen make the rich richer: when a person cannot afford the full money bail, he or she can often pay a commercial bail bondsmen a fee, generally 10% of the bail set by the court. The bail bondsmen signs paperwork with the court, pledging to be responsible for the remaining amount of the bond if the person doesn’t return to court. In reality, commercial bail bondsmen are almost never asked to make good on those pledges, but they always keep the “fee” in every case. The United States is one of only two countries in the world where commercial bondsmen profit from people’s inability to pay for their own freedom.

Money bail punishes everyone but the wealthy. Being jailed pretrial leads to people losing their jobs, not being able to care for their children, and losing contact with loved ones. Being held pretrial makes both conviction and incarceration more likely: people held pretrial are more likely to plead guilty simply to put an end to their case, with the hopes of returning home, and judges are statistically more likely to sentence someone to jail once they have been held in jail pretrial. This means that people held on money bail are more likely to be convicted and sentenced because they don’t have readily available cash to hand over. Most people held pretrial are not dangerous: around 68% of pretrial detainees have been charged only with drug, property, or public order crimes.

Money bail costs taxpayers. The United States spends $38 million a day to detain people pretrial, and nearly $140 billion a year. That cost is borne by taxpayers and could be redirected into education, housing, and economic development.

Although each state has basic laws governing how people are held or released pending trial, most states ask cash-strapped counties to develop their own local guidelines and the programs to support release. In most of the country, the bail bond industry has lobbied against these local reforms. Not surprisingly, then, many local jurisdictions simply do not have the resources or incentives necessary to replace money bail with a system that would ensure that people who posed a serious risk to their communities are the ones who stay in jail, while those that are not a risk, regardless of their income, would be released. An effective effort to end money bail must empower states and counties to create equitable programs that hold people based on necessity rather than wealth.

Voters Want to End Money Bail

There is an emerging consensus among criminal justice reformers, victims’ rights groups, law enforcement, and conservative groups that our bail system is broken and must be fixed.

State legislatures across the country have implemented reforms to move away from money bail. In other places, courts have struck down bail systems as unconstitutional, because money bail creates a two-tiered system: one for the very rich and one for everyone else.

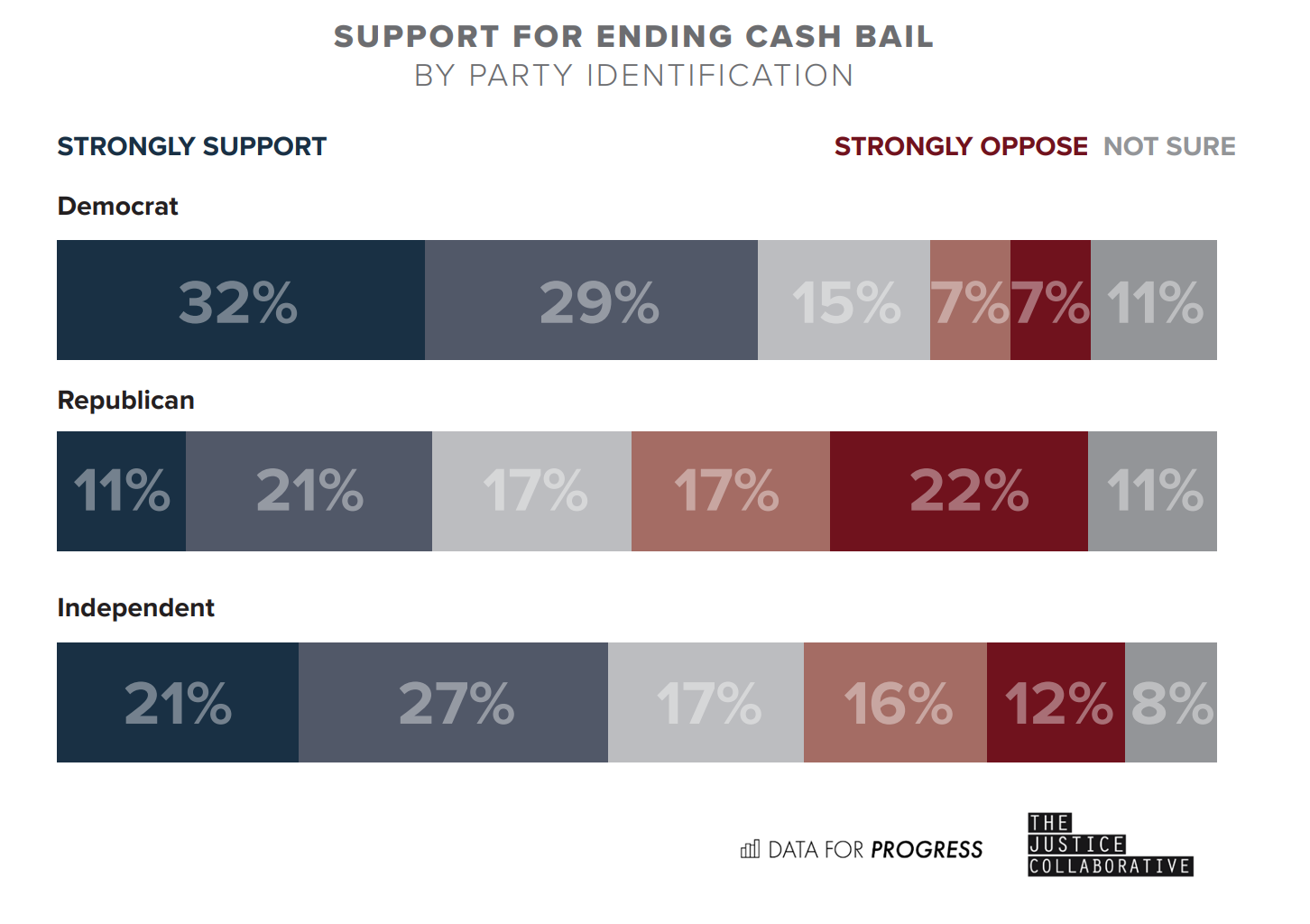

Polling from Data for Progress indicates that people across the country want to see the elimination of money bail; in fact, twice as many want to see the end of money bail as support it. Our polling shows that both Democrats and Independents strongly support the elimination of money bail. Even the majority of Republicans either support or do not oppose the elimination of money bail.

The Proposal

To help states and local systems implement the cash-free systems voters demand, it’s time to pass the End Money Bail Act.

The bill provides local systems the resources they need to create local money free programs. It requires that local governments create pretrial systems that:

Release most people pretrial. The bill allows courts to detain a person pending trial only after a judge finds by clear and convincing evidence that no pretrial release conditions will suffice and detention is necessary to keep the community safe from violent physical force against another person or conduct that will cause another person significant bodily harm. Under all circumstances, the judge is required to use the least restrictive conditions possible and waive all fees for people who are unable to pay. If there is evidence that the defendant will not return to court in an effort to avoid prosecution, that risk can be addressed through appropriate pretrial conditions. The EMBA rests on two coequal goals: ending money bail and lowering jail populations, both of which are consistent with increasing public safety.

Provide checks on detention, including requiring that all defendants are represented by counsel, are only detained after a hearing in front of a judge, can take expedited appeals of a detention decision, and receive periodic reviews of all detention orders.

Create an Independent Review Committee made up of national experts to help local systems design and implement effective pretrial release systems and to evaluate and report on the success of those systems.

Maintain and provide case level data to the National Pretrial Reporting Program, to be maintained by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, so that experts can understand what works, what doesn’t, and what might be keeping people incarcerated unjustly. The bill also requires the creation of a public dashboard, so that anyone can analyze data from participating jurisdictions.

Existing Alternatives to Money Bail: The Federal System

Creating equitable systems for pretrial release is the most important component of the End Money Bail Act. This core premise is not radical; the federal criminal courts eliminated money bail throughout the country in 1984.

Instead of releasing someone based on a person’s cash on hand, federal courts hold a hearing to determine if the person charged poses any danger to the community or is likely to not come back to court. If so, the court then determines whether there are non-financial conditions of release, like reporting to a supervision officer, drug testing, or other conditions, that will address those concerns. The judge may detain the person pretrial only after finding that there are no sufficient conditions or combination of conditions to protect the community or ensure the defendant’s return to court. The person charged is represented by an attorney at the hearing, and can appeal the judge’s order.

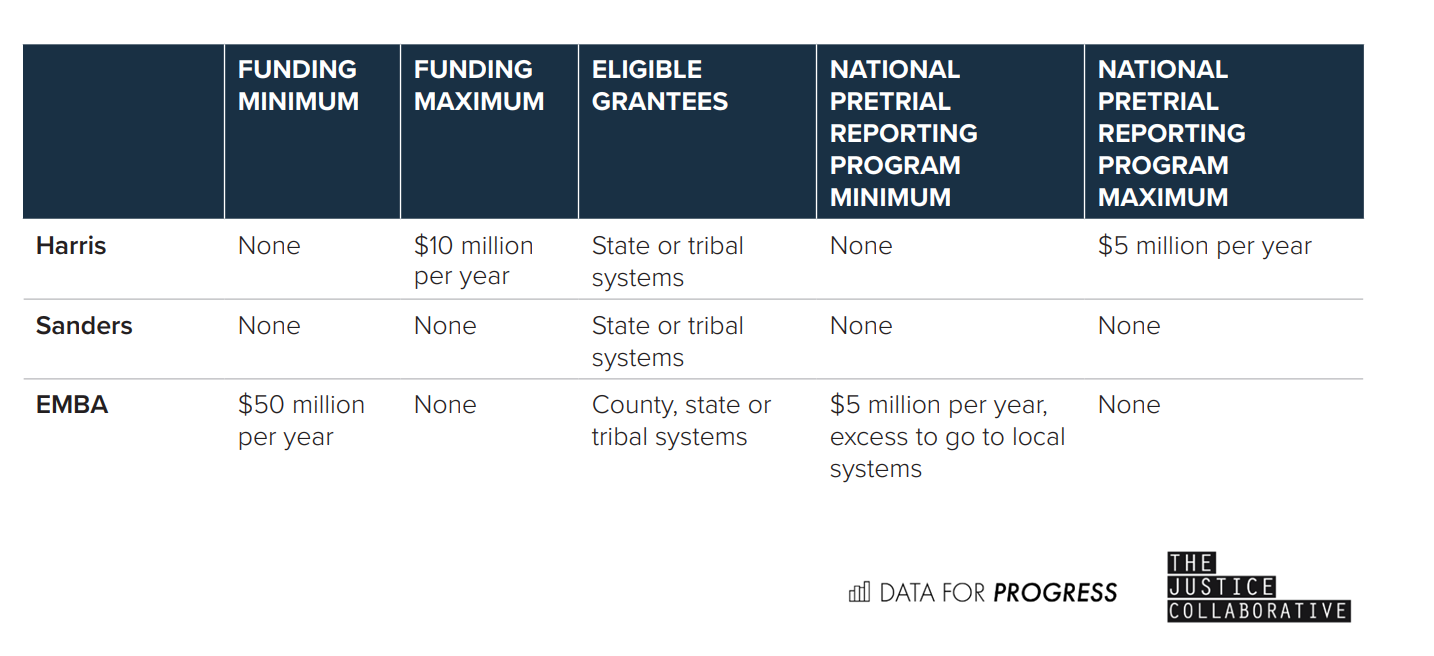

The End Money Bail Act implements the most progressive features of the federal bail system, going farther than either the Senator Bernie Sanders or Senator Kamala Harris bills in creating a comprehensive, evidence-based plan for reform. Two similar pieces of proposed legislation, introduced by Harris and Sanders, also create incentives for local systems to create release programs similar to the federal bail system.

Alternatives to Money Bail in State and Local Systems

Several states have enacted broad reforms to their pretrial detention systems in the last several years, including New Jersey, California, and New Mexico. Like the federal system, each of these states requires individualized hearings before a person can be held pending trial, and none allow a person to be held based only on an inability to pay money bail. Reforms have been enormously successful. The District of Columbia prohibited the use of money bail in the 1990s. D.C. releases 94% of people charged with crimes, of whom just over 1% are rearrested for a violent offense while pending trial.

The End Money Bail Act incentivizes states and counties to adopt release systems that mirror D.C.’s robust and successful program. By requiring a presumption of release in most cases, limiting detention to only those people that involve the risk of violent force or serious bodily injury and for whom no other conditions would be sufficient, and requiring periodic review of detention orders, the End Money Bail Act will create fairer and more effective systems than any other proposal.

How the Proposals Incentivize Local Systems

The End Money Bail Act will transform money bail in participating jurisdictions by providing states and local governments with the money they need to implement just and effective programs.

The bill also funds a national pretrial reporting program, which would collect, analyze, and share data through publicly accessible dashboards. The bill ensures that funds will be allocated to a substantial number of participants by setting robust funding floors, as opposed to ceilings, with mechanisms to redistribute any excess funds to additional local systems.

In short, the EMBA ensures that these reforms remain funded, rather than limiting funding available to make reforms. The bill further incentivizes local systems to achieve significant reductions in pretrial detention by making the grant renewable for those systems that are in substantial compliance with ambitious benchmarks established by the bill. Through sufficient and thoughtful funding floors, the bill ensures that local systems will have the resources they need to succeed, no matter what.

Although both Sen. Harris’s and Sen. Sanders’s bills allocate money to systems through grant funding, neither create funding floors, instead leaving it to the Assistant Attorney General to decide how to fund local systems and at what level. Even more problematic, the Harris bill proposes restrictive funding limits, which will dramatically reduce the number of jurisdictions that can participate in the program. Further, no other program makes counties eligible to be grantees, even though counties generally bear the costs for developing and implementing pretrial release programs.

Conclusion

The elimination of money bail has never been a more urgent problem, nor has there ever been more political will to dismantle this unjust and outdated relic.

The End Money Bail Act is the strongest piece of legislation directed at eliminating reliance on money bail nationwide. By directing more resources to implementation and data collection, it creates a greater chance of success than any other bill addressing bail reform at the national level. By requiring that local governments enact robust and equitable pretrial release programs, it will go further to reduce unjust pretrial detention than any other bill. By adequately funding a national pretrial reporting program and ensuring that the program has access to all available data, the End Money Bail Act will make pretrial release systems more transparent to both governments and the public at large, so that we can all access and analyze underlying data.