Resolving Our Medical Debt Crisis: The Case for Health Care Consumer Financial Protection

Erin C. Fuse Brown, J.D., M.P.H. Associate Professor of Law and the Director of the Center for Law, Health & Society at Georgia State University College of Law.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

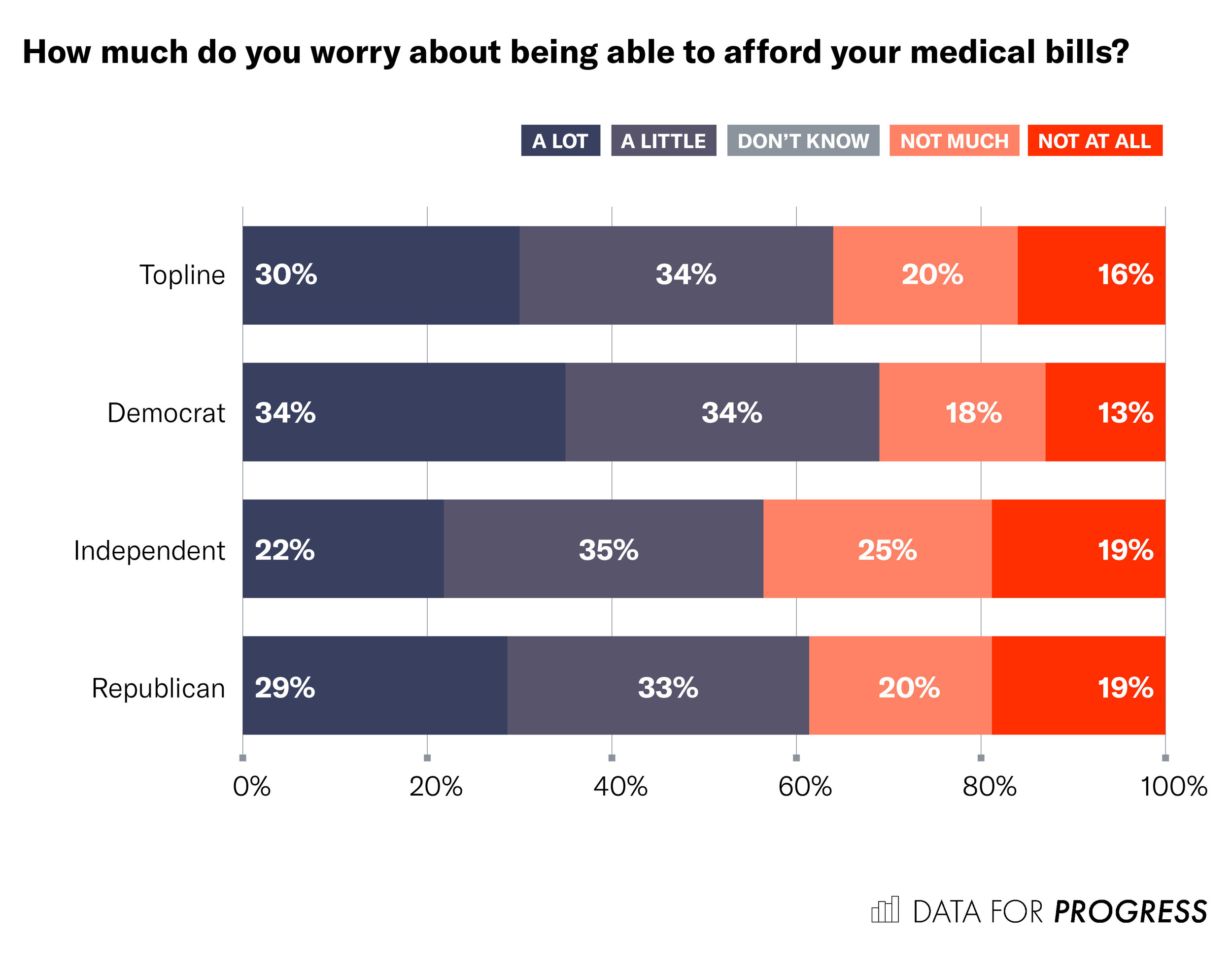

Unfair health care pricing and aggressive medical debt collection practices have created financial devastation for millions of Americans. Current national and state policies are inadequate to protect consumers, resulting in tremendous stress on households. Polling by Data for Progress and the Lab, a policy vertical of The Appeal, shows that a majority of Americans have either forgone or delayed necessary health care—with 19% reporting that they have done both—because they were afraid of the cost. Nearly two-thirds of Americans (64%) worry about being unable to afford medical bills to some degree, while only 36% of Americans do not worry about being able to afford medical bills.

This crisis can be addressed by stronger and better enforced consumer protection laws. The federal government, for example, can fill gaps in existing protections by making compliance with fair pricing and collection rules a condition of participating in Medicare—something nearly all hospitals and physicians must do as a financial necessity. But even without federal intervention, states can resolve this crisis by expanding financial protections and providing private remedies under their consumer protection laws.

A model policy to resolve the health care debt crisis should include the following:

Consumer protections against medical debt that apply to a broad range of providers.

Financial assistance thresholds that are standardized by patients’ household income and medical expenses to limit providers’ discretion on eligibility.

Strong protections against debt collection actions by providers or their collection agents.

A private remedy and enforcement action by state officials for violations of medical debt protections.

The majority of Americans support proposals to reign in hospital billing and debt collection practices:

69% of Americans supported the proposal of requiring all hospitals and health care providers to provide free or discounted care to uninsured or self-pay patients who are low income. Only 21% of Americans opposed the proposal, and 10% were unsure.

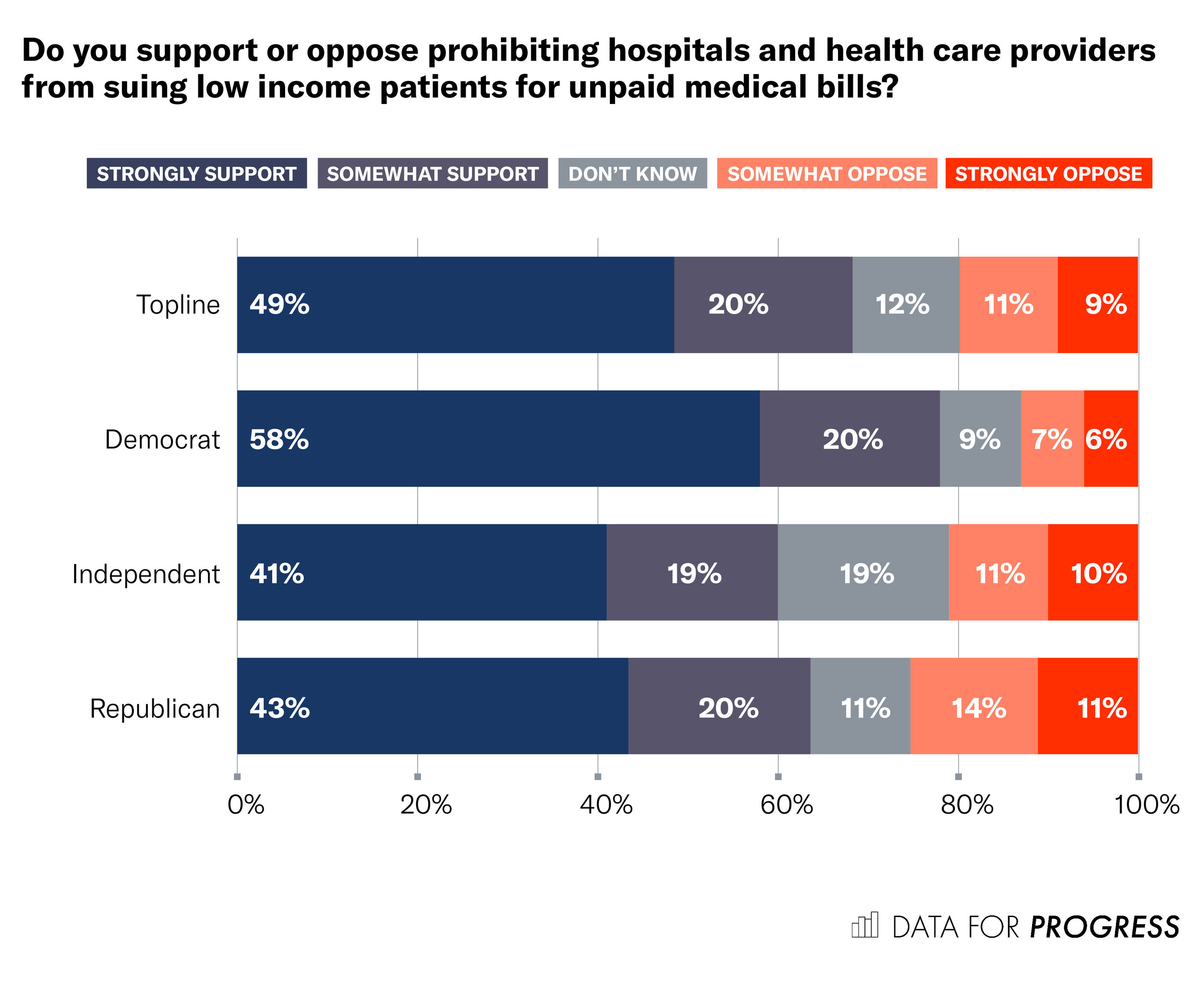

More than two-thirds of those surveyed support policies that would prohibit health care providers from suing their patients, garnishing patients’ wages, or seizing patients’ homes to recover medical debt. One in five oppose such policies.

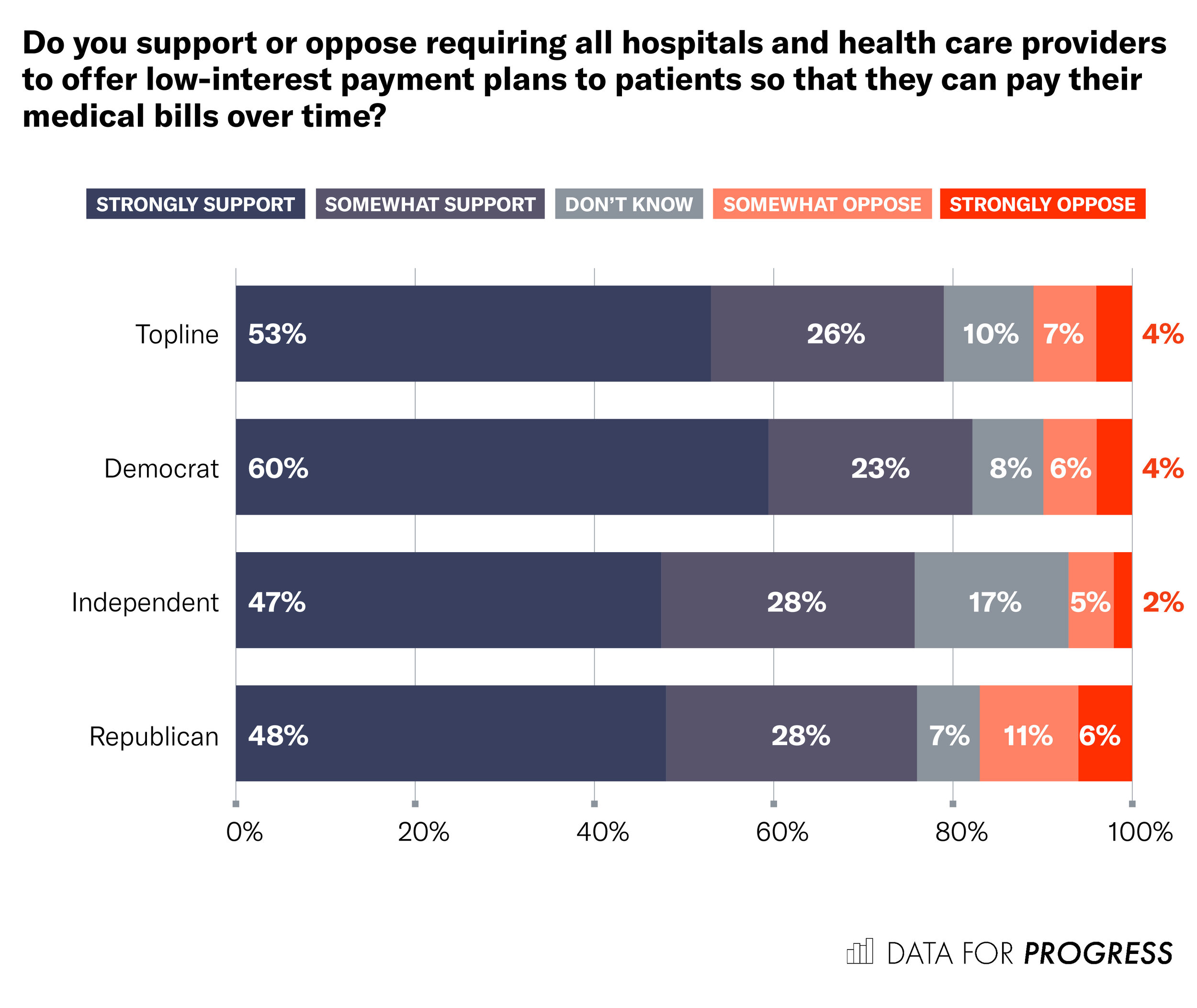

Americans, regardless of political affiliation, support policies requiring health care providers to offer low-interest payment plans by a margin of 8 to 1.

BACKGROUND

The Heavy Burden of Medical Debt

Heather Waldron, mother of five, received emergency intestinal surgery at University of Virginia Medical System (UVA), the state’s flagship nonprofit teaching hospital. Waldron’s insurance policy had lapsed due to a clerical error, and UVA sued Waldron and her husband for $164,000, forcing the sale of the family’s home to recoup the debt. Waldron is not alone—UVA has sued over 36,000 patients over six years, including low-income patients and its own employees, garnishing their wages and putting liens on their homes.

Throughout the country, hospitals and physician groups have sued tens of thousands of patients for unpaid medical bills. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, unmanageable medical debt pushed millions of Americans into financial distress, ranging from damaged credit to bankruptcy. Lawsuits against patients have not stopped even as the pandemic has pushed millions of individuals out of their jobs and providers have received $175 billion in federal aid. The United States is the only economically developed country where a slip and fall and a trip to the emergency room could spell financial ruin or bankruptcy.

Health insurance coverage is no longer sufficient to protect people from medical debt. Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), millions gained insurance coverage and the financial protection that comes with it. Increasingly, however, insurance coverage does not ensure financial protection for patients as the costs of health care are rising and the patient is picking up a larger portion through out-of-pocket spending. In particular, deductibles, the amounts patients must pay out-of-pocket before insurance kicks in, have been rising much faster than wages or inflation. Deductibles have increased more than 150% over the past decade from $533 on average in 2009 to $1,350 in 2018. Many of the coverage gains of the ACA have been lost during the pandemic, which has increased the number of uninsured Americans by an estimated 3.5 million due to the loss of job-based coverage.

Even with insurance coverage, medical debts are widespread. In a 2014 study, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) reported that 52% of all debts on credit reports were medical debts, by far the most common type of debt. And unlike other types of debt, consumers are often unaware of their medical debts or they are struggling to get the bills resolved with their providers and their health insurance plan.

As the burden of out-of-pocket expenses grows, consumers are increasingly worried about the cost of health care. Recent polling by Data for Progress and the Lab, a policy vertical of The Appeal, sheds light on Americans’ concerns over medical debt and the affordability of necessary health care:

Polling results show that 51% of Americans have either forgone or delayed necessary health care—with 19% reporting that they have done both—because they were afraid of the cost.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans (64%) worry about being unable to afford medical bills to some degree, while only 36% of Americans do not worry about being able to afford medical bills.

Drivers of Medical Debt: Inflated Prices and Harsh Debt Collection Practices

The U.S. medical debt burden stems from the twin problems of inflated hospital prices and harsh debt collection practices. Hospitals routinely charge uninsured patients the highest “chargemaster” prices, the rack rates of the health care industry, while government and commercial payers are charged a third or half as much. And even insured patients pay inflated prices when they receive out-of-network care, for which there are no negotiated rates. Even if the patient’s health plan pays for part of the care, the provider often bills the patient for the balance between the amount paid by insurance and the provider’s full charges, a practice called surprise medical billing. Although Congress passed the federal No Surprises Act as part of the December 2020 coronavirus relief legislation to protect patients from surprise out-of-network bills, the overarching problem of medical debt will still continue in other forms. The rising number of uninsured and the increasing burden of out-of-pocket costs for those with insurance means many patients face unaffordable medical bills.

Harsh debt collection practices exacerbate the problem of unmanageable medical bills. These collection practices include selling the debt to collection agencies, suing patients, seeking foreclosure or liens on patients’ homes, garnishing wages, seizing bank accounts and property, charging high interest rates, requiring up-front payment before providing additional care, and even seeking arrest for failing to appear in court for a debt collection hearing. These tactics inflict significant financial, emotional, and health-related hardship upon patients. Patients may lose their wages, homes, or creditworthiness, or be pushed into bankruptcy. Unmanageable medical debt has been associated with higher levels of stress, anxiety, and poorer health. Indebted patients may have difficulty securing future health care because providers may not serve patients with outstanding medical debt. Further adverse health effects may ensue as patients self-ration medically necessary care, prescription drugs, or other necessities like food or shelter to pay their medical bills.

Often, patients lack legal representation and are ill-equipped to fight debt collection actions, which increasingly dominate the dockets of state civil courts. One report noted that more than 70% of debt collection cases end in default judgment against the debtor, usually because the debtor did not respond to the action or show up in court. Once the court enters judgment, the debt balloons from added court fees and accrued interest.

Medical debt and harsh collection practices disproportionately affect Black communities. Black individuals are more likely than whites to carry medical debt, due to the wealth gap between these groups and the higher rates of uninsurance among Blacks. Debt collection suits are far more prevalent in Black communities, with double the rate of judgments as in mostly white neighborhoods. Historically marginalized communities are more susceptible to the burdens of medical debt in part because individuals in these communities have fewer financial and legal resources to draw upon when medical bills hit.

It all adds up to a situation where nearly a quarter of Americans between ages 18-64 carry medical debt and have come to fear medical bills more than the illness itself. Medical debt is the predominant reason debt collectors pursue individuals and a major contributor to personal bankruptcies. In short, the U.S. has a medical debt crisis.

EXISTING LAWS ADDRESSING MEDICAL BILLING AND DEBT COLLECTION

Inadequate Federal Protections Against Medical Debt Collection

Existing federal laws offer limited protections to patients faced with medical debt lawsuits. The ACA contained new Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules limiting the billing and collection practices of tax-exempt hospitals, and the CFPB pushed changes in how consumer credit reports treat medical debt. These federal standards are inadequate and underenforced, and if the Supreme Court strikes down the ACA, then many of these protections may disappear altogether. Instead, the most promising models for consumer protection come from state fair medical billing and collection laws.

The IRS rules, among other provisions, prescribe fair billing and collection requirements for tax-exempt hospitals. First, these hospitals must maintain and widely publicize their financial assistance policy, including eligibility criteria for free or discounted care. The IRS rules, however, do not prescribe how hospitals are to determine eligibility for financial assistance, leaving these determinations to the hospitals’ discretion. Second, hospitals must limit the amounts charged to patients who are eligible for financial assistance to “amounts generally billed” to insured patients for emergency or medically necessary care. Hospitals may not charge such patients “gross charges,” which are the hospitals’ full, undiscounted rates. Third, the IRS rules limit nonprofit hospitals’ ability to engage in aggressive debt-collection practices. Hospitals may not use “extraordinary collection actions” unless the hospital has made reasonable efforts to determine the patient’s eligibility for financial assistance.

On their face, the IRS rules for tax-exempt hospitals create financial protections for low-income patients by reducing the amount the hospital can bill and limiting the use of aggressive collection tactics. Still, there are three main gaps in the rules’ protections.

The IRS rules are underinclusive—they do not apply to the 43% of hospitals that are for-profit or government-run or to private physician practices or other types of providers that tend to be for-profit.

The rules give hospitals complete discretion to determine eligibility for financial assistance, which is the trigger for the rules’ protections. For example, a hospital could adopt a narrow financial assistance policy with very restrictive income or asset requirements or make applying for financial assistance so onerous that few can complete the process.

The rules are underenforced by the IRS, with no reported case of hospital sanctions despite widely publicized violations.

Although the IRS rules aim to protect vulnerable patients from the financial burdens of medical debt, the rules are underinclusive, easy to manipulate, and underenforced, leading to an inadequate patchwork of protections.

Additional federal oversight comes from the CFPB, an independent federal agency that oversees consumer financial products or services, including debt collection and credit reporting. The CFPB published two reports on the treatment of medical debt on credit reports, concluding that medical debts are pervasive and tend to be overly penalized in the calculation of consumers’ credit scores. The CFPB reports led to two industry changes. First, FICO voluntarily moved to weigh medical debts less than nonmedical debts in calculating an individual’s credit score and to disregard all paid medical collection accounts. Second, three major credit reporting agencies agreed to refrain from reporting medical debts on credit reports until 180 days delinquent to allow for insurance payment and resolution. The credit reporting agencies also agreed to remove from credit reports all debts that were paid in full or are being paid by insurance. Practically speaking, these policies reduce the degree to which consumers’ credit ratings are damaged by stand-alone medical debts and medical bills that have been paid or are being disputed with insurance providers. However, consumer advocates warn that the risks of nonpayment still persist because many consumers remain unaware of the medical debts on their credit reports.

While the federal protections against medical debt collection remain inadequate, several states have passed laws providing more robust consumer protections that serve as better models for consumer financial protection in health care.

State Fair Pricing and Medical Debt Collection Laws

Several states have passed fair medical pricing and collection laws that apply to all hospitals, regardless of tax status or ownership. As detailed in Appendix A, at least eleven states have passed laws that limit the amount all hospitals may charge to patients who fall below defined income levels, and three additional states have state-funded financial assistance programs available to low-income patients at all hospitals. For example, California’s Hospital Fair Pricing Act limits how much California hospitals and emergency physicians may charge to uninsured patients who earn less than 350% of the federal poverty limit (FPL) or insured patients whose medical bills exceed 10% of household income. New Jersey requires all hospitals to provide free care to patients with an income below 200% of FPL and offer discounts for patients with incomes between 201-300% of FPL, and hospitals may not charge uninsured patients with incomes up to 500% of FPL more than 115% of the Medicare rate for the same service. By defining income and affordability thresholds, these states curtail hospitals’ discretion in determining eligibility for financial assistance and standardize these limits across all hospitals. With the exception of California, most state laws do not apply these financial assistance requirements to non-hospital providers, such as physician groups.

In addition, as detailed in Appendix B, at least eighteen states have laws that restrict providers’ medical debt collection practices, including limitations on interest rates hospitals may charge on medical debt, limits on hospitals’ ability to foreclose or place a lien on a patient’s home or other property, limits on wage garnishment, obligations to offer payment plans, and requirements for the timing and procedure for assigning medical debt to a collection agency. The scope of these limits on collection practices varies, with some states applying them broadly to all patients, and others limiting the protections by the patient’s income, uninsured status, or eligibility for financial assistance. Again, California serves as a model by substantially restricting nearly all these collection practices by for-profit and nonprofit hospitals as well as emergency physicians. Contrary to some industry fears, California’s law has not caused widespread financial strain on hospitals. Instead, it has leveled the field for financial assistance, and most hospitals have voluntarily adopted policies that go beyond the requirements of the law.

States can also enhance enforcement, including through a private right of action for victims of unlawful practices and through enforcement by the health department or state attorney general. Connecticut provides a model for private enforcement by making it an unfair trade practice for any provider to seek payment from patients or report debts to credit reporting agencies stemming from prohibited medical bills.

Designating medical billing practices as an unfair trade practice creates a private remedy for those harmed by unlawful medical billing and collection practices with the potential to recover attorneys’ fees and punitive or treble damages, creating valuable incentives for attorneys to take these cases. Nearly every state has an Unfair and Deceptive Acts or Practices (UDAP) law, and legislatures can designate certain health care billing practices as unfair trade practices under their state statute.

States have created the blueprint for model laws to protect patients from the twin causes of the medical debt crisis—excessive prices and harsh debt collection practices. Public support for such policies is strong. Polling data from Data for Progress and the Lab indicate that the majority of Americans support proposals to reign in hospital billing and debt collection practices:

69% of Americans supported the proposal of requiring all hospitals and health care providers to provide free or discounted care to uninsured or self-pay patients who are low income. Only 21% of Americans opposed the proposal, and 10% were unsure.

More than two-thirds of those surveyed support policies that would prohibit health care providers from suing their patients, garnishing patients’ wages, or seizing patients’ homes to recover medical debt. One in five oppose such policies.

Americans, regardless of political affiliation, support policies requiring health care providers to offer low-interest payment plans by a margin of 8 to 1.

MODEL POLICIES TO ADDRESS MEDICAL BILLING DEBT COLLECTION

Taking these state laws as a model, a better national policy would decouple fair pricing and collection rules from hospitals’ tax status and make compliance with these rules a condition of participation in Medicare—nearly all hospitals and physicians participate in Medicare as a financial necessity. This proposal would require all Medicare-participating providers to limit the amounts they charge uninsured patients or insured patients with large medical expenses and to limit their collection practices with respect to these patients.

Additionally, more states could adopt broad consumer protections against excess medical bills and harsh debt collection practices. The National Consumer Law Center (NCLC) proposed a comprehensive Model Medical Debt Protection Act that could serve as a template for robust state legislation.

A model state policy for fair medical prices and debt collection, described in Appendix C, would include the following features:

Consumer protections against medical debt should apply to a broad range of providers.

Financial assistance thresholds should be standardized by patients’ household income and medical expenses to limit providers’ discretion on eligibility.

The policy should contain strong protections against debt collection actions by providers and/or their collection agents.

States should create a private remedy and enforcement action by state officials for violations of medical debt protections.

CONCLUSION

The medical debt crisis stems from the twin problems of unfair pricing and harsh medical debt collection practices. The ACA’s rules for tax-exempt hospitals took a step toward ensuring fairness in hospital billing and debt collection, but gaps in the IRS rules’ coverage and enforcement have left many patients unprotected. Thus, we need stronger national and state policies to require fair pricing and medical debt collection practices, and we need for these rules to cover a wider range of health care providers to protect all financially vulnerable patients. States can fill many of the substantive gaps in financial protections for health care consumers; they can also go further than the federal government, typically through the creation of private remedies under consumer protection laws for medical billing practices that are designated as unfair or deceptive acts or practices. It is time to resolve the U.S. medical debt crisis and protect patients as consumers.

POLLING METHODOLOGY

From 9/11/2020 to 9/14/2020 Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1,212 likely voters nationally using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is +/- 2.8 percentage points.

APPENDIX A: STATE LAWS ADDRESSING MEDICAL CHARGES

| STATE | TYPE OF PROVIDER | LIMITS ON CHARGES | CITATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRA rules | Federally tax-exempt hospitals | Prohibits charging patients eligible under the hospital’s financial assistance policy more than the amounts generally billed to insured patients. Does not specify standards for financial assistance eligibility. | 26 U.S.C. § 501(r); 26 C.F.R. § 1.501(r)-1 to 1.501(r)-7 |

| California | All hospitals (except rural hospitals), Emergency physicians | Requires free or discounted care to uninsured patients earning <350% of FPL or insured patients whose medical bills exceed 10% of household income. | Cal. Health & Safety Code § 127405 (hospitals); Cal. Health & Safety Code § 127452 (emergency physicians) |

| Colorado | All hospitals | Provides state-provided financial assistance for uninsured patients who earn <250% of FPL.l Limits the amounts such patients may be charged to the lowest negotiated rate from a private health plan. | Colo. Rev. Stat. § 25-3-112 |

| Connecticut | All hospitals | Prohibits charging more than the cost of care to uninsured patient with income ≤250% of FPL. | Conn. Gen. Stat. § 19a-673 |

| Illinois | All hospitals | Requires free care for uninsured patients earning <200% of FPL, or <125% of FPL for rural or critical access hospitals, and unspecified discounts for uninsured patients earning between 200-600% of FPL, or up to 300% of FPL for rural and critical access hospitals. For these patients, hospitals may not collect more than 25% of patient’s family income in a 12-month period. | 210 Ill. Comp. Stat. 89/10 (2013) |

| Maine | All hospitals | Requires free care for state residents earning <150% of FPL. | 10-144 Me. Code R. § 150 |

| Maryland | All hospitals (acute care and chronic care hospitals) | Requires free care for patients earning <200% of FPL and discounted care for patients earning between 200-500% of FPL. | Md. Code Ann., Health-Gen. § 19-214.1 |

| Massachusetts | Acute care hospitals and community health centers | Requires free care for uninsured or medically indigent patients earning <150% of FPL, discounted care for those earning 150-300% of FPL. | 118 Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 118E §§ 66-70; 101 CMR 613; 614 |

| Nevada | Hospitals with ≥100 beds and are located in a county with ≥2 licensed hospitals | Requires free care for indigent patients who are uninsured, ineligible for public assistance, earn an income of $438/month for one person or $588/month for two people, or $588 + $150 for each additional family member. | Nev. Rev. Stat. §§ 439B.300 to 439B.340 |

| New Jersey | All hospitals | Requires free care for patients earning ≤200% of FPL and discounted care for patients earning 200%-300% of FPL or patients with medical expenses >30% of gross annual income with limited assets. Limits charges to uninsured patients earning up to 500% of FPL to 115% of Medicare rates. | N.J. Stat. Ann. § 26:2H-12.52; N.J. Admin Code § 10:52-11.8 |

| New York | Nonprofit hospitals and all hospitals seeking reimbursement from the Indigent Care Pool | Requires discounted care for uninsured patients earning <300% of FPL, capped cost for patients earning <100% of FPL, sliding scale for patients earning between 100-250% of FPL, and no more than amount hospital receives from its highest volume payer for patients with incomes between 250-300% of FPL. | N.Y. Pub. Health Law § 2807-k |

| Oklahoma | All hospitals | Requires discounted care (charging no more than Medicare rates) for uninsured patients earning up to 300% of FPL. | Okla. Stat. tit. 63 §1-723.2. |

| Rhode Island | All hospitals | Requires free care for patients earning ≤200% of FPL and discounted care for patients earning between 200-300% of FPL. | R.I. Gen. Laws § 23-17-43 |

| South Carolina | All inpatient hospitals in Medicaid program | State-provided free care for patients earning ≤100% of FPL and discounted care for patients earning between 100-200% of FPL with limited assets. | S.C. Code Ann. Regs. 126-515, 126.520 |

| Washington | All hospitals | Requires free care for uninsured patients with a family income of ≤100% of FPL and discounted care for patients earning between 100%-200% of FPL. | Wash. Admin. Code § 246-453-040 |

| NCLC Model Medical Debt Protection Act | “Large health care facilities,” including all hospitals and all health professionals who provide services at a covered facility, outpatient clinics affiliated with hospitals, and large group practices with revenues >$20 million annually | Free care for those earning <200% FPL, financial assistance discounts (based on Medicare rates) for those earning between 201-400% FPL and those earning between 401-600% with large medical bills. Additional financial assistance for patients earning <600% FPL with medical bills >10% of annual household income. | NCLC website |

APPENDIX B: STATE LAWS ADDRESSING MEDICAL DEBT COLLECTION

APPENDIX C: MODEL POLICY FOR FAIR MEDICAL BILLING AND DEBT COLLECTION

Consumer protections against medical debt should apply to a broad range of providers, including all types of hospitals, larger physician groups, freestanding emergency rooms, outpatient clinics, and others. All of these provider types can saddle patients with unmanageable medical debts, and IRS rules only apply to tax-exempt hospitals. An example is the NCLC’s Model Medical Debt Protection Act, which would apply to “large health care facilities,” including all hospitals, affiliated outpatient clinics, physicians who provide services at covered facilities, and large physician groups with annual revenues exceeding $20 million.

Financial assistance thresholds should be standardized by patients’ household income and medical expenses to limit providers’ discretion on eligibility. The policy would require all Medicare-participating providers to provide free care to patients earning less than 200% of FPL and limit the amounts charged to self-pay patients with incomes less than 400% of FPL as well as any patient whose out-of-pocket medical bills exceed 10% of annual household income. The protections would thus extend not just to uninsured patients, but also to underinsured patients with high out-of-pocket expenses. By defining the income and affordability thresholds, the policy would replace hospitals’ discretion in determining eligibility for fair billing and collection with level and predictable standards across all hospitals. Under a federal policy, health care providers could receive further financial enhancements to their Medicare payments if they offer more generous financial assistance to patients than prescribed by the standard policy. As with the state law counterparts, there can be some flexibility in the requirements as applied to rural or critical access hospitals that may struggle to comply with the general rule.

The policy should contain strong protections against debt collection actions by providers and their collection agents. First, providers should be required to offer eligible patients an option for an extended payment plan with no or limited interest. Second, providers should be prohibited from attaching or forcing the sale of a person’s primary residence while it is occupied by the patient, his or her spouse, or any dependent. Third, providers should be prohibited from seeking wage garnishment or seizing bank accounts or personal property while a person is making a good faith effort to pay the debt. Fourth, providers may assign a debt to a collection agency and report nonpayment to a credit reporting agency only if the patient has stopped making any payments for a defined period of time (e.g., 180 days past due), the provider has made reasonable efforts to contact the patient, and the collection agency agrees to the same limits on collection to which the provider is subject under the law. Other actions, including seeking a patient’s arrest or denying the patient medically necessary care, should be strictly prohibited.

States should create a private remedy and enforcement action by state officials for violations of medical debt protections. Violations of any of these provisions should constitute an unfair trade practice under the state UDAP statute, allowing a private cause of action for money damages, injunctive relief, and attorneys fees. The policy should also provide for an administrative enforcement authority in a state official or agency, such as the State Attorney General.