If We Want Racial Justice, We Have to Take on Amazon

By Jamaal Bowman

No company in America has profited more from the coronavirus pandemic than Amazon. While millions have lost loved ones, watched their jobs disappear, shuttered their businesses, and watched their savings go up in smoke, Amazon has seen its stock price skyrocket and taken in more than $5 billion in profits. The company is now worth more than a trillion dollars. Jeff Bezos is the world’s richest man, with an estimated net worth of more than $200 billion. He’s projected to become the world’s first trillionaire by 2026.

When a company gets this big, there are costs. When one person gets this obscenely wealthy, there are costs. Costs to the health of our economy, and costs to our democracy. Today, our communities are paying these costs.

While Amazon may have started as a marvel of ingenuity, the company is now building its power by depriving others of their own. Its business model is engineered to maintain the power of a small group of mostly white, mostly male overseers at the expense of Black and brown communities, echoing the foundations of white supremacy in this country. Amazon’s exploitation of the pandemic, against the backdrop of the nationwide protests following the killing of George Floyd, have made that clear for the whole country to see.

The corporation has delayed the provision of basic protections to workers in its warehouses and on its delivery routes, including masks and hand sanitizer. At the JFK8 fulfillment center on Staten Island, workers in the early days of the pandemic reported that they had just a handful of sanitizer pumps for a facility the size of 18 football fields. The company has held back critical information on the spread of the coronavirus in its warehouses, including how many workers have fallen sick, even though workers - and, sometimes, their elected officials - have asked for the information over and over again. Some workers, taking the task into their own hands, have estimated that more than 2,000 Amazon workers have contracted the coronavirus. At least ten workers have died.

Almost all of the Black people who work at Amazon work in the company’s warehouses or delivery routes, and they are from many of the same working-class communities hit hardest by the pandemic. Meanwhile, the majority of its tech workers in Seattle and executive leadership are white.

Some Amazon workers have bravely tried to raise the alarm on the dangerous conditions they were forced to work in. Amazon fired at least six of them, and began using surveillance technology to target and intimidate others. All of the frontline workers who spoke up and Amazon fired were Black. A leaked memo showed that Amazon planned to smear one of these workers with tired anti-Black tropes, saying that he wasn’t “articulate.”

The company can get away with all this because today, Amazon functions as a monopoly. Its power and scope are on par with corporate colossuses of centuries past, names like Standard Oil and U.S. Steel, which today we associate with out-of-control dominance and exploitation.

It’s not just about how Amazon treats its workers. The company also squeezes the sellers on its platform, many of them Black business owners for whom Amazon is a lifeline to a bigger market. Because Amazon controls access to so much of the online consumer market, it can set the terms of how businesses sell online. Third-party sellers have reported that Amazon has repeatedly coerced them to accept new fees and the use of Fulfillment by Amazon, the company’s shipping service. Amazon has even used data from its third-party sellers to compete with them using its own brands.

Amazon also controls many of the roads and bridges of the Internet through Amazon Web Services (AWS), its cloud computing service. If you’re watching Netflix, if you’re scrolling Instagram, if you’re on a Zoom call, you are using AWS. Amazon has aggressively pursued multi-billion federal contracts for its cloud computing software, going so far as to hire a former NSA director, the same person at the center of the agency’s illegal wiretapping controversy, to go after a $10 billion contract with the Pentagon.

The company also has little regard for democratic norms, regularly using its might to bend elected officials to its will. It was clear when Amazon tried to make a backroom deal to build its HQ2 in my backyard of Queens, financed by the taxes every working person in New York pays. And it was clear when Amazon tried to turn over the Seattle City Council after its members dared to ask the corporation to pay its fair share in taxes.

These abuses of power aren’t a coincidence. They aren’t a side effect of how Amazon runs its business. They are the business model itself, one built on surveillance, coercion, exploitation, and, at the end of the day, total dominance. As one fired warehouse worker put it, “Amazon is a modern-day slave system.”

Jeff Bezos and other Amazon executives like to paint themselves as allies to Black people. Bezos even went so far as publicly responding to a racist customer in the wake of the protests following the killing of George Floyd, vowing in an Instagram post to “support this movement that we see happening all around us, and my stance won’t change.”

Their words ring hollow when you look at Amazon’s actions in regards to Black people. And it’s not just about Black workers - Amazon also actively contributes to the over-policing and degradation of Black communities. Just this Friday, Amazon called the police when a Black warehouse worker who quit Amazon accompanied my future colleagues, Rep. Rashida Tlaib and Rep. Debbie Dingell, to try to visit a Detroit facility.

That’s not a one-off. Through its subsidiary Ring, Amazon has aggressively courted partnerships with police departments across the country. This has placed one of the largest private surveillance networks in the country into the hands of police, with no public oversight, helping to fuel racial profiling and mass incarceration. These partnerships allow police to get access to user footage en masse without a warrant, probable cause, or judicial review, subverting the laws designed to protect us. Just like complaints from workers, Amazon has swept aside complaints from racial justice groups and civil rights organizations about the dangers of its surveillance tools.

Amazon has also helped supercharge the separation and deportation of Black and brown immigrants by providing technology support to ICE. And Amazon situates its operations near Black and brown communities, exposing families and neighborhoods to heavy air pollution. Amazon subsidiary Whole Foods even fired workers for showing support for Black Lives Matter.

Elected officials in Congress and at the local level have significant leeway to rein in Amazon and make the company more accountable and humane - if they’ll only exercise it.

Over the past year, the House Antitrust Subcommittee has led an investigation into the power of Amazon and other tech giants, one of the most sweeping antitrust investigations we’ve seen in decades. In the coming days, the members of that committee are expected to release a set of recommendations to curb Amazon’s power - breaking up their business into manageable, and governable, parts. This is an opportunity for everyone to fundamentally rethink Amazon’s place in our society and for lawmakers to lead by providing a roadmap for regulators to reshape Amazon in the months and years ahead.

There are more ways that lawmakers can - and should - take action. We can enact stronger whistleblower protections to safeguard workers who expose unsafe working conditions, which would encourage others to speak up with less fear. We can also pass a real federal wealth tax, so that CEOs like Jeff Bezos aren’t able to horde the billions they collect by squeezing every penny out of workers and our communities. State lawmakers can do that, too. More than a dozen attorneys general are looking into worker abuse, antitrust violations, and more. On the local level, lawmakers can end Amazon’s partnerships with police departments, pass outright bans on facial recognition (like Portland, Oregon, just did), and refuse to subsidize the corporation’s growth in our communities.

These policies are popular with voters. As part of a September survey, Data for Progress asked voters their opinion about Amazon and major technology companies in general.

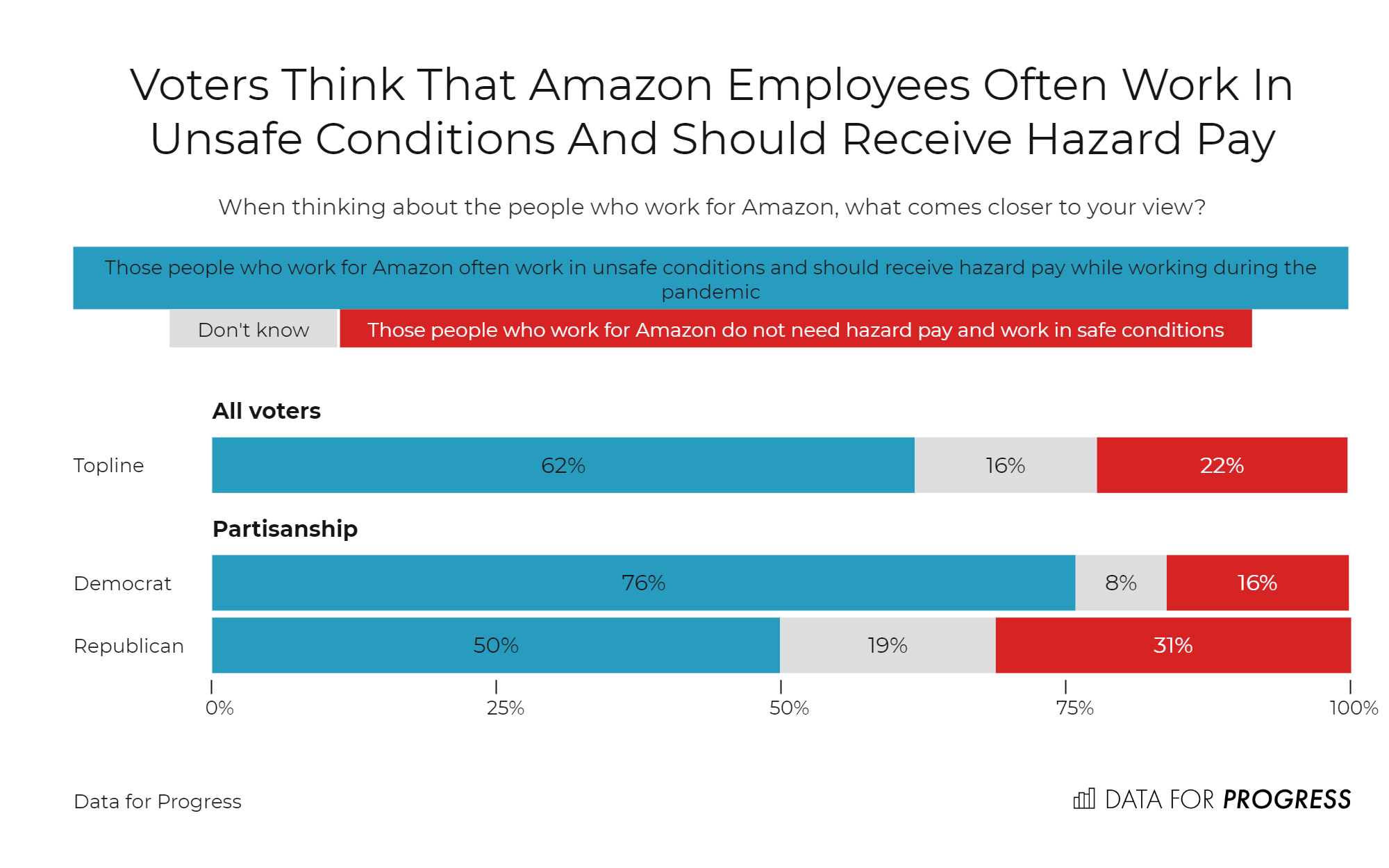

Likely voters were first asked whether they think that Amazon employees often work in unsafe conditions and should receive hazard pay or, conversely, whether they think Amazon employees mostly work in safe conditions and don’t need hazard pay. A majority of voters (62 percent) agreed with the former - that Amazon employees work in dangerous conditions and deserve hazard pay for the duration of the pandemic.

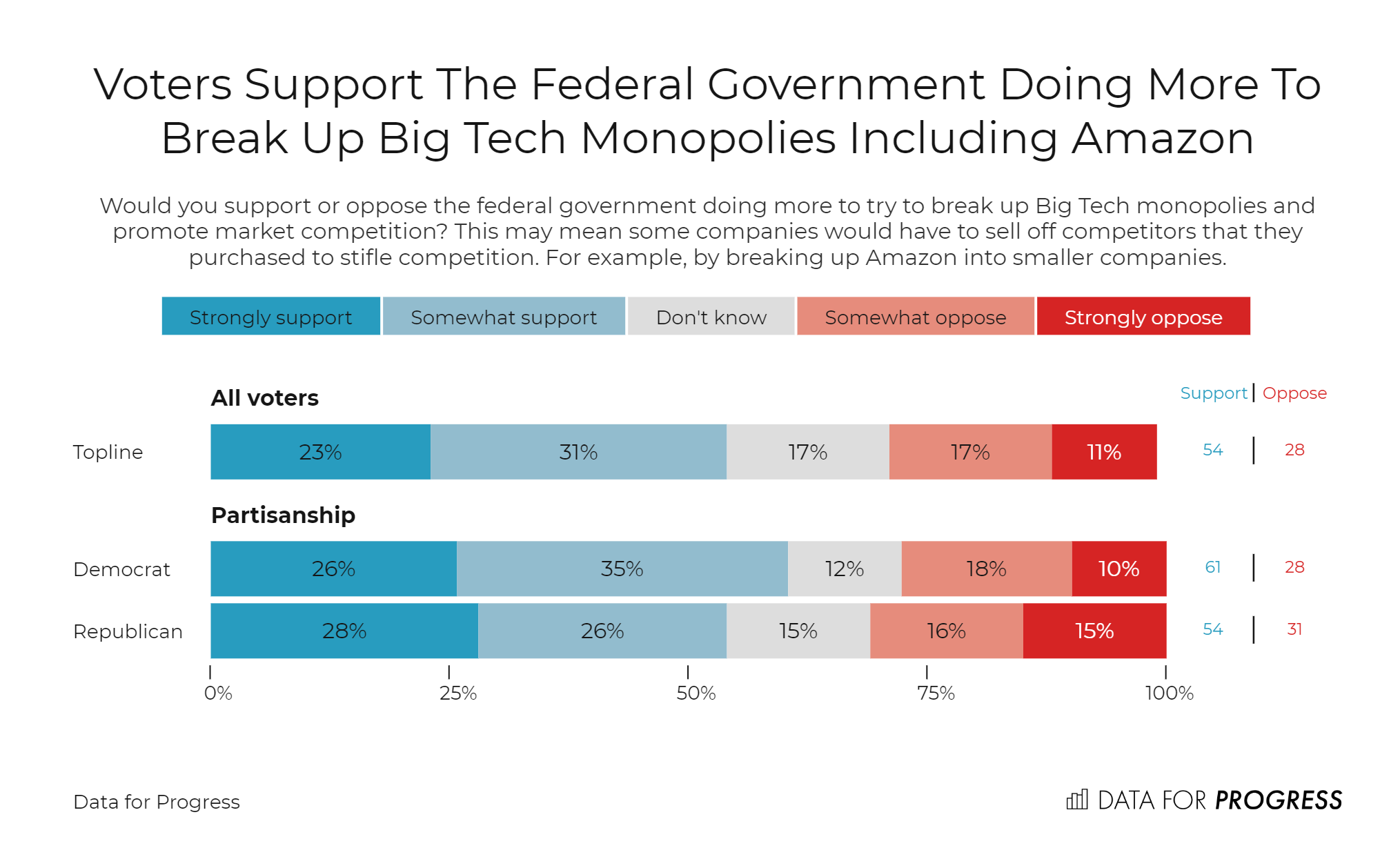

Next, Data for Progress asked if voters would support or oppose the federal government doing more to break up big tech monopolies, including Amazon, to promote increased market competition.

Voters support a breakup by overwhelming margins, with 54 percent supporting and only 28 percent opposed. This includes a majority of both self-identified Democrats and Republicans, who back it by 33- and 21-point margins, respectively.

It’s clear that voters see Amazon’s monopoly power as a problem. By allowing corporations to concentrate power and wealth, we will eventually put our democracy at risk. The past few months have shed light on just how ruthless Amazon can be, particularly towards people of color. And as we know, the treatment of Black people has always been the canary in the coal mine for how corporations view democracy. That’s why it’s so important for us as lawmakers to sound the alarm. Unless elected officials step up and take on Amazon, the company’s power to exploit Black workers, harm Black communities, and degrade our democracy will only grow.

Jamaal Bowman (@JamaalBowmanNY) is the Democratic Party’s nominee in New York’s 16th congressional district.

From September 25 through September 26, 2020, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1,162 likely voters nationally using web-panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is +/- 3 percentage points.