Republicans Don't Know Anything About Their Party. That's Very Bad for American Democracy.

By Ethan Winter

While the packaging of Republican Party politics has evolved since 2000, what remains unaltered is a bedrock commitment to regressive tax cuts, a sharp curtailment of worker power, and the elimination of health, environmental, and economic regulations. This is an agenda that, structurally, has limited electoral appeal. Indeed, there is a reason that since 1988, excluding 2004, no Republican presidential candidate has exceeded 48 percent of the popular vote.

In this post, I seek to explore whether or not the Republican Party’s positions on economic issues defines how likely voters view the party. I am especially interested in how likely voters that self-identify as Republicans conceptualize their own party.

As part of a Data for Progress survey fielded in mid-November 2020, I posed five questions to voters where I asked them to assign policy positions to each of their major parties. To do this I employed an A/B split, where half the sample was asked if the Democrats supported a policy and the other half of the sample was asked if the Republicans supported that policy. The four issues I tested are 1) protecting the ability of those with pre-existing conditions to get health insurance; 2) expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act; 3) raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour, and 4) allowing companies to dump mining debris into mountain streams.

We actually know a lot more about the policy positions that politicians and parties hold than we give ourselves credit for. This is in large part because voting records are publicly available. It’s there, not in private anonymous comments, that elected officials reveal their expressed preferences, as opinion is combined with power to fundamentally reshape people’s lives.

For the better part of the last decade, Republicans in Washington, D.C. have fought to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the law that provided protections for those with pre-existing conditions and expanded Medicaid. They’ve been joined in this effort by the legal wing of the party, which continues to fight for the overturning, and actors at the state level of who have blocked the expansion of Medicaid, or, allowed it to expand but only on conservative terms — which means, in material terms, fewer people got health insurance.

While there are certainly dissident elements of any political party, especially in the American context where our two-party system has a habit of forcing the creation of grand coalitions, being able to clearly assign policy positions to candidates and then political parties should be seen as an essential feature for the functioning of an electoral democracy. What these results indicate is that there is work to be done in making this a reality.

Healthcare

Denying people health insurance because of pre-existing conditions is both unconscionably cruel and despised by voters. As a result, Republicans will routinely lie about their position on this issue. The most outrageous instance of this is when former Senator Cory Gardner cut an ad with his mom, a cancer survivor, saying he was fighting to protect those with pre-existing conditions. There are certainly efforts to fact check but as this result suggests, the effects of these efforts may be limited. But, importantly, Republican activists don’t leap to their feet to denounce these politicians for lying and deviating from conservative orthodoxy. Instead, they largely stay quiet, equipped with the knowledge that their agenda is unpopular and obfuscating their true position is the best way to accumulate political power.

While 78 percent of likely voters know, correctly, that Democrats support protections for those with pre-existing conditions, a plurality (45 percent) of likely voters, incorrectly, think that Republicans do as well. Among voters that self-identify as Republican, 76 percent think that their party supports these protections.

Likely voters do a slightly better job assigning policy positions when it comes to Medicaid expansion. Seventy-two percent of voters know that Democrats support its expansion. Still, a quarter (25 percent) of likely voters think that Republicans support this policy. Among Republicans, this number sits at 38 percent.

Workers

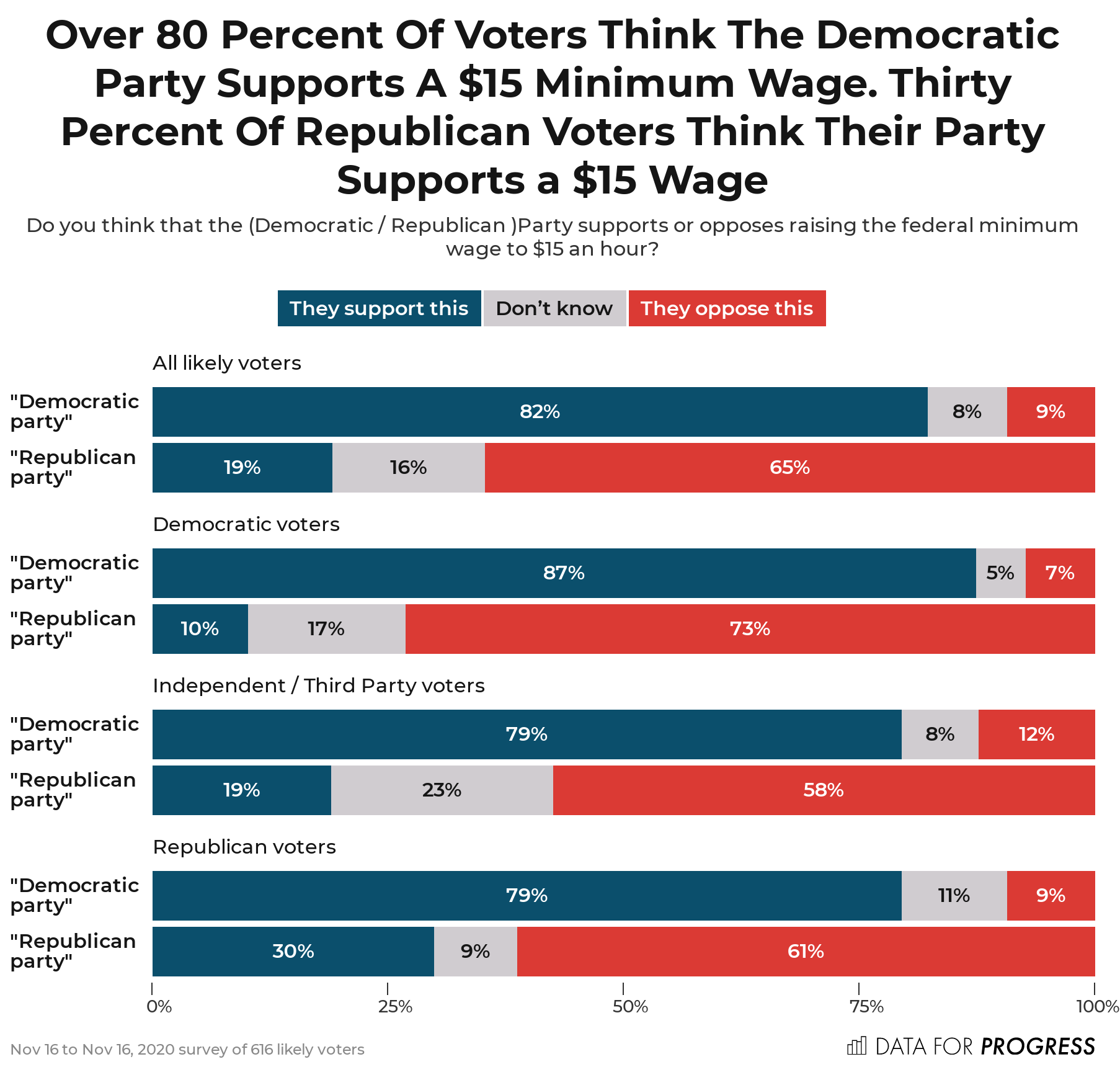

Next, I asked likely voters about the partisan support for $15 minimum wage. I found that 82 percent and 19 percent think that the Democratic and Republican Parties, respectively, support this wage hike. Nonetheless, almost a third (30 percent) of Republicans think that their party supports increasing the minimum wage to $15 an hour.

Regulations

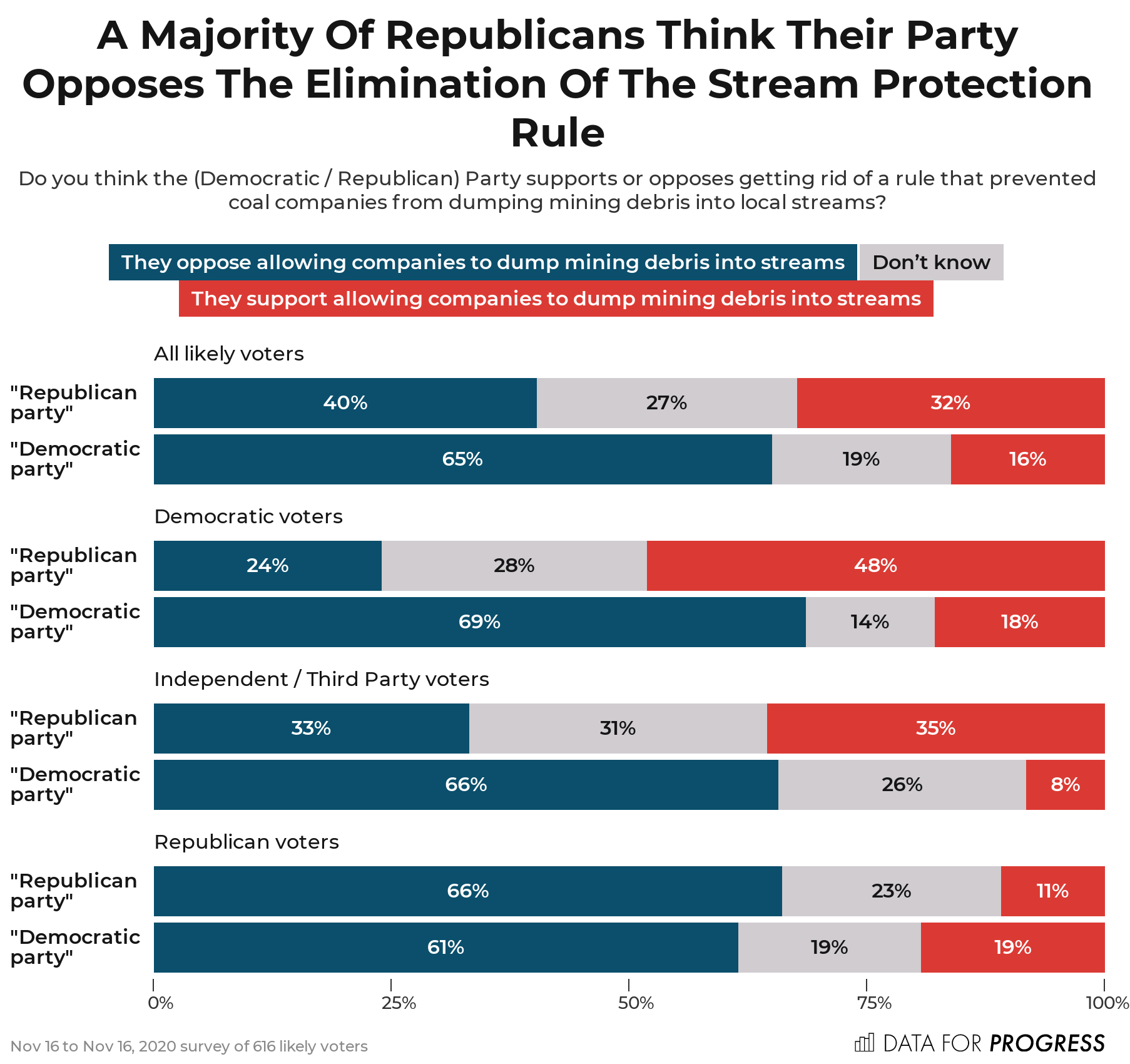

On regulations, I asked voters about the parties’ position on the Stream Protection Rule. The Obama administration implemented this rule made it harder for coal companies to, in effect, dump mining debris into streams. In 2017, the Senate used the Congressional Review Act to reverse this rule. This vote fell roughly along partisan lines, all Republicans voted for its rollback, save Sen. Susan Collins, and all Democrats voted to keep the rule except four: Senators Joe Donnelly, Heidi Heitkamp, Claire McCaskill, and Joe Manchin. Of these Democrats, only the last still has their job as a Senator.

Roughly two-thirds (65 percent) of likely know that the Democratic Party opposes allowing mining companies to dump debris into streams. A plurality (40 percent) of likely voters incorrectly think that Republicans oppose mining debris being dumped in streams. This is even more pronounced when one looks at attitudes among Republican voters: Sixty-one percent of them know that Democrats oppose this but 66 percent also think that Republicans oppose this.

Conclusion

The political scientist E. E. Schattschneider argued that “democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties.” For Schattschneider, parties solved an information problem that arises with advanced (post-)industrial society. Put simply, the kinds and quantity of policies that arise are of such complexity and scale that no one person could ever hope to know enough to make an informed voting decision. The parties then are to work as heuristics. With their platforms they work to simplify the great issues of the day. But if this metric by which we are to judge their relative success, they have evidently failed.

In 1950, a committee Schattschneider chaired released a report called “Towards a More Responsible Two-Party System.” The report advocated for, in brief, more ideologically distinct parties which would offer voters a clear choice. Recent trends in partisan polarization have caused voters to question this conclusion. But these findings suggest that despite the ideological drift of the parties in Congress, voters don’t always see the choices they have as being distinct on issues where the parties are in fact quite different.

As for why Republicans voters in particular don't see a difference between the two major parties, there are many causes. Motivated reasoning likely plays a large role. If a Republican voter doesn’t think mining companies should dump debris into a stream, why would they think their elected representative would support this policy?

This is a long-running trend, of voters, especially Republican voters, denying the extremism of the positions that the party holds on questions of political economy. Matthew Yglesias, formerly of Vox, terms this phenomenon “the politics of incredulity.” For him, such voters are a major reason why these conditions persist. He argues “voters find [the Republican Party’s position on economic issues] so outlandishly bad that they’ll only believe someone espouses them if you can convince them first that the person in question is a heartless monster.” For Republican voters in particular, Yglesias adds: “Consequently, people who align with Republicans on broad values themes — whether opposition to abortion rights, love of guns, patriotism, or panic at the thought of a diversifying country — find it simply not credible that their champions are actually running on a politically toxic agenda that would clearly lose elections.”

The parties’ ability to shape their images is limited, however. To fully understand these results we must look to the central role that the media plays in portraying parties and, through that, determining who wins and who loses elections. Perhaps some reporters view it as impolite to assign policy positions to Republicans, especially when their beliefs are so obviously and hideously cruel. For politics to rebalance at a healthier outcome where voters are actually able to assign correct positions to the parties, we will need a new kind of reporting, one that doesn’t flinch from assigning policy views to the parties or drawing out the implications of these ideas in clear and materially-grounded terms. Without that, our politics will continue to march on in a fog of confusion.

Ethan Winter (@EthanBWinter) is an analyst at Data for Progress. You can email him at ethan@dataforprogress.org.

On November 16, 2020, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1160 likely voters nationally using web-panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ±2.9 percentage points.