Do voters disapprove of Biden — or rising gas prices?

By Ahmad Ali and Colin McAuliffe

The rise of gas prices in America is strongly correlated with presidential job disapproval. American households cannot simply avoid purchasing certain goods when their prices rise. Retail gasoline is an essential and inelastic good — its increase in price tends to have little effect on the demand for car travel. Tens of millions of parents drive their children to school and tens of millions of workers commute to their jobs using a gas vehicle. Drivers then go to the pump and begrudgingly pay higher and higher prices to fill their tanks all so their gas consumption may continue as usual.

There are political consequences for the sitting president whenever American household budgets are constrained by rising gas prices. Analysis of monthly presidential approval between 1976 to 2007 suggests “that gas prices did exert an independent effect on presidential approval above and beyond traditional economic measures.” Another and more recent study measuring pocketbook voting attitudes finds that “constituencies with longer average driving times to work are more likely to hold the president accountable for gasoline price increases.”

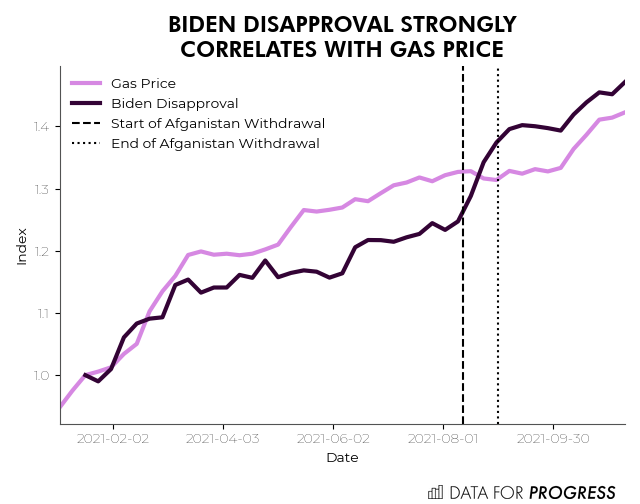

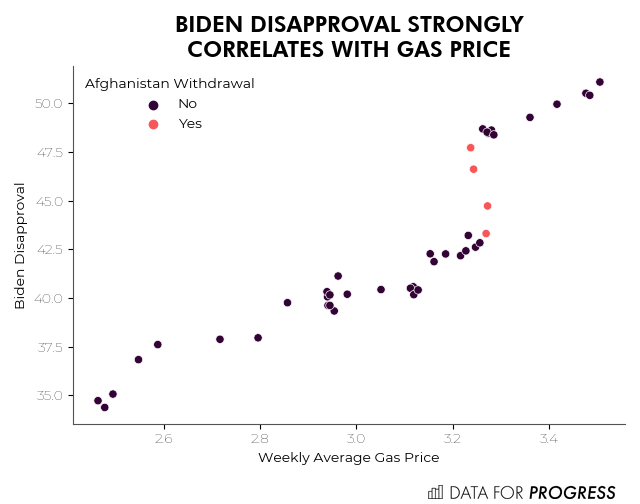

We can then observe this same trend play out during the course of the Biden presidency. The latest increase in retail gasoline prices between January 18th to November 8th of this year is strongly correlated with presidential job disapproval, as modeled by FiveThirtyEight using 891 polls conducted between January 23rd and November 14th.

The rising price of retail gasoline and this shift in presidential job disapproval likely would have been even more correlated this year — but there was a sudden upswing in disapproval during the final withdrawal of U.S. Armed Forces from Afghanistan despite a marginal decrease in the price of retail gasoline. Removing polls conducted during this specific disapproval shock results in significant correlation (R2 = 0.96).

This trend between rising gas prices and job disapproval is particularly concerning given the myriad of positive economic indicators that should otherwise reward the President — such as strong income growth for the bottom of the income distribution beyond inflation and continued reductions in child poverty due to the expanded Child Tax Credit. Workers are quitting their jobs at staggering rates this year and flexing their power to freely exit. Further, firms are not taking the labor crunch lying down, and many are announcing investments in productivity-enhancing technology which could end up reducing inflation pressure in the long run. These are clear policy successes — and our response to them should not be to curtail worker power, choke off business investment, and ultimately reduce the incomes of those at the bottom of the income distribution.

The President should consider executive prescriptions in the short term that remedy the recent rise of retail gas prices to a reasonable degree; his latest call for the Federal Trade Commission to investigate whether or not “illegal conduct” of oil and gas companies is to blame for the latest increase in prices is a powerful first step. The President must also reduce American reliance on foreign energy and continue his work in securing popular investments that will electrify public transit and deploy electric vehicles. This approach will produce significant political, economic, social, and environmental dividends for decades to come.

Ahmad Ali (@RealAhmadAli) is Press Secretary at Data for Progress.

Colin McAuliffe (@ColinJMcAuliffe) is a Co-Founder of Data for Progress.