Redistricting Is Going Surprisingly Well for Democrats

By Joel Wertheimer

Conventional wisdom suggests that, because Republicans control more of the redistricting process than Democrats, they will inexorably benefit from this redistricting cycle. But an analysis of each of the 50 states’ specific or expected outcomes leads to the opposite conclusion: When redistricting is finished, more districts in 2022 will be to the left of Joe Biden’s 4.5-point national margin against Donald Trump than in 2020, and there is an outside chance that the median seat will be to the left of the nation as a whole.

The following analysis only looks at whether a seat is to the left or right of Joe Biden’s margin in 2020 and not whether a “seat” is gained or lost in redistricting, as Cook Political does. Given the significantly reduced power of incumbency, the key question for determining power in a given congressional election is the partisan lean of the tipping point congressional district. This is also the most relevant small-d democratic concern: In an election that results in a 50.1 percent to 49.9 percent split, are the voters in the 50.1 percent able to elect the Congress of their choosing?? Even if Democrats lose power this year, the partisan valence of the map may allow them to regain the House in 2024 — unlike in 2012.

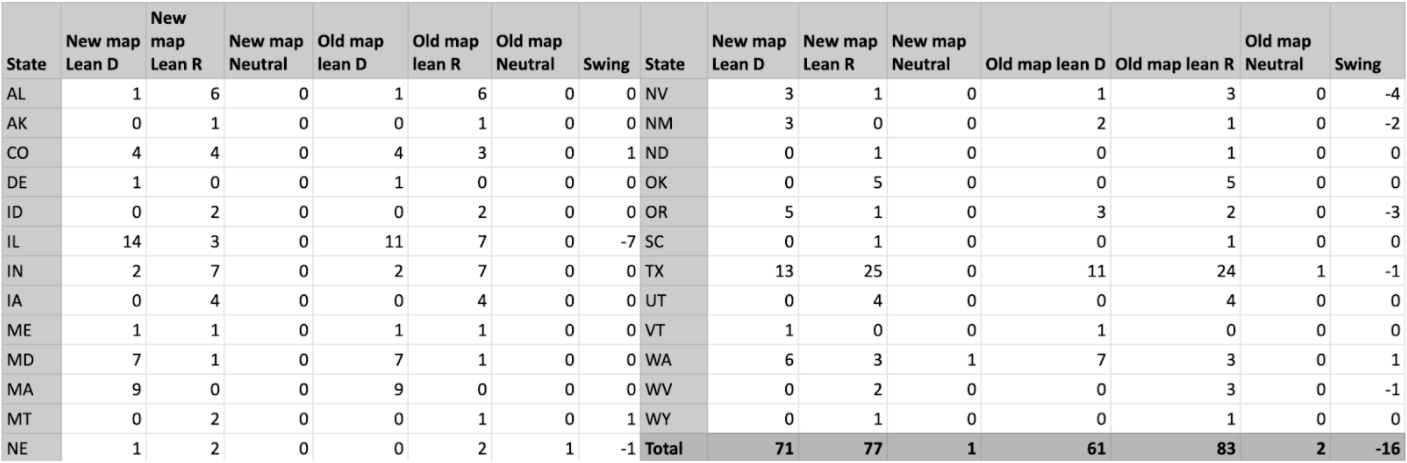

In the 25 states that have concluded redistricting (or are single-member states), and where the maps are not facing state courts that are hostile to the maps,* Democrats have improved their standing compared to 2020, with a net of 16 seats moving to the left of Joe Biden’s +4.5-point national margin in 2020.

Nine states have not finished redistricting, but will likely not shift the partisan makeup of their seats–whether because they are already gerrymandered maximally, or because they have announced they will not.

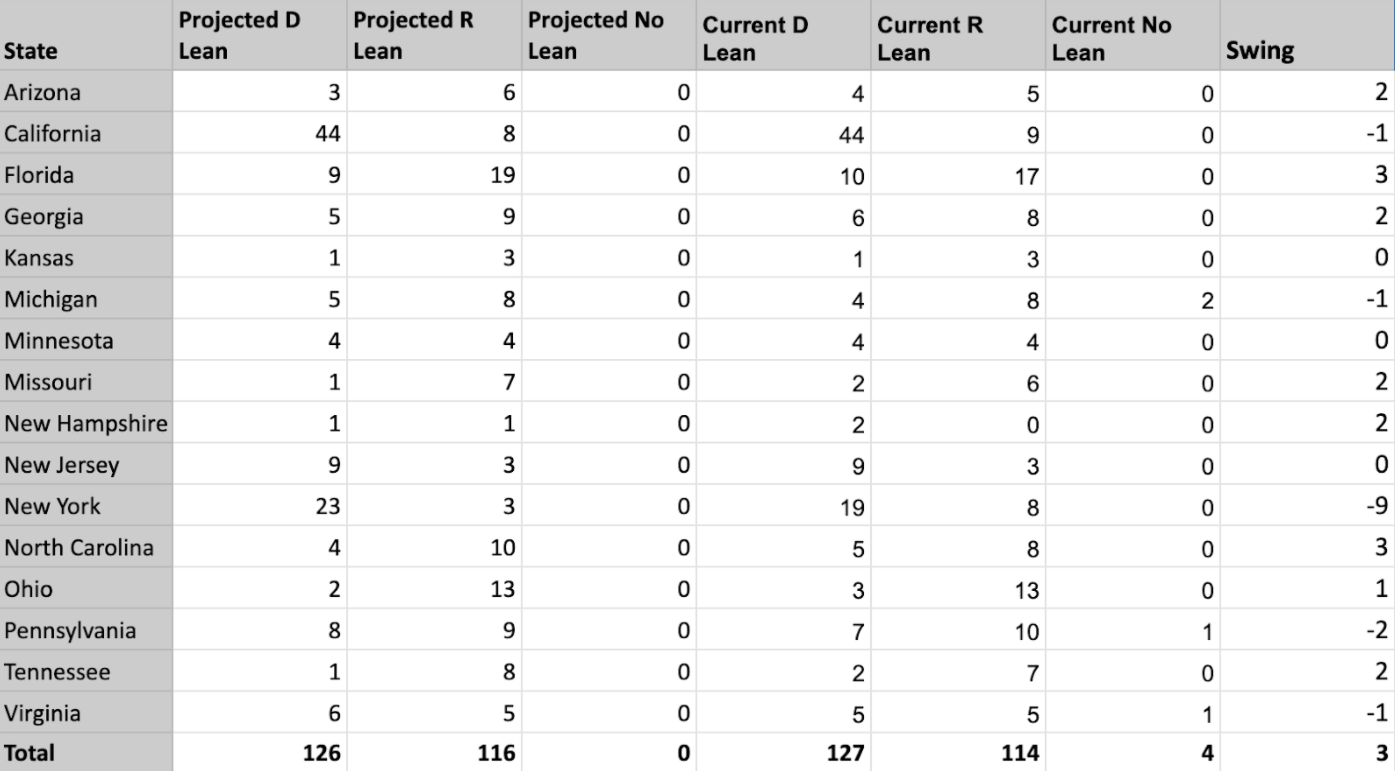

Those thirty-four states account for 195 of the 435 seats in the country. The remaining 240 seats are in fifteen states, including the Ohio and North Carolina maps that have been approved by their state governments but seem likely to be changed by state Supreme Courts. With reasonable assumptions about what will happen in those states – based on draft maps likely to be approved, maps that have been reported on, or simple conjecture – we can project 212 seats to be to the left of Joe Biden’s 4.5 point 2020 margin, compared to the 203 seats that were to the left of his margin in 2020.

It’s worth noting that, on the whole, these are relatively conservative assumptions. Interestingly, if the courts of North Carolina and Ohio counteract the extreme partisan gerrymanders enacted by Republicans in their states, Democrats could achieve partisan parity nationally. North Carolina’s Supreme Court, which is a 4-3 Democratic majority, already enjoined the GOP’s adopted map. Ohio’s Supreme Court, which is 4-3 Republican, but with a swing vote, indicated at oral argument that the Court was upset with the Republicans for passing a map that blatantly disregarded the state constitutional gerrymandering amendment. Holding all other assumptions constant, if the Ohio map is remade 10-5 by the state Supreme Court and the North Carolina map changed to 8-6, the map would be 217-217-1.

Why is the conventional wisdom suggesting that Democrats are doomed this cycle so wrong? First, analysts are failing to compare to the relevant baseline: the 2011 redistricting cycle. In 2011, Republican trifectas or veto-proof majorities controlled the redistricting of 219 seats, whereas Democratic trifectas controlled the redistricting of just 44 seats, with at-large districts, split control, or independent commissions deciding the remainder. This cycle, those numbers are 193 Republican and 94 Democratic seats, due to Democratic consolidation of power in blue states like New York and the introduction of commissions in a number of states. Moreover, the number of commission states perhaps understates the Democratic advantage: California is the largest commission state in the country by a vast margin, making up nearly half of the commission seats, and seems poised to put 44 of its 52 seats to the left of Joe Biden’s 2020 margin.

Second, Democrats have been much more aggressive this cycle, and in particular are unpacking their own seats. Illinois and Oregon gerrymandered much more aggressively for explicitly partisan purposes than Democrats have in the past. New York is poised to do the same, having moved from a Republican state senate majority in 2011 to a Democratic supermajority in both state chambers in 2021. Sometimes, these Democratic moves will not create new elected seats, but it will matter for partisan fairness. In Nevada for example, three of the four seats are currently held by Democrats, but Susie Lee and Steven Horsford’s districts actually lean to the right of Joe Biden’s national margin in 2020. The new map, however, makes all three seats more Democratic than Biden’s +4.5-point margin.

Third, and conversely, Republicans have not used their gerrymandering power as aggressively as Democrats toward a goal of maximizing the overall partisan lean of the national map. In Texas, for example, Republicans made the state's districts lean more to the right than the state overall, reduced the number of competitive seats significantly, and protected their incumbents from competitive races. They accomplished that goal, however, by leaving 13 Democratic seats in place rather than attempting a more aggressive gerrymander.

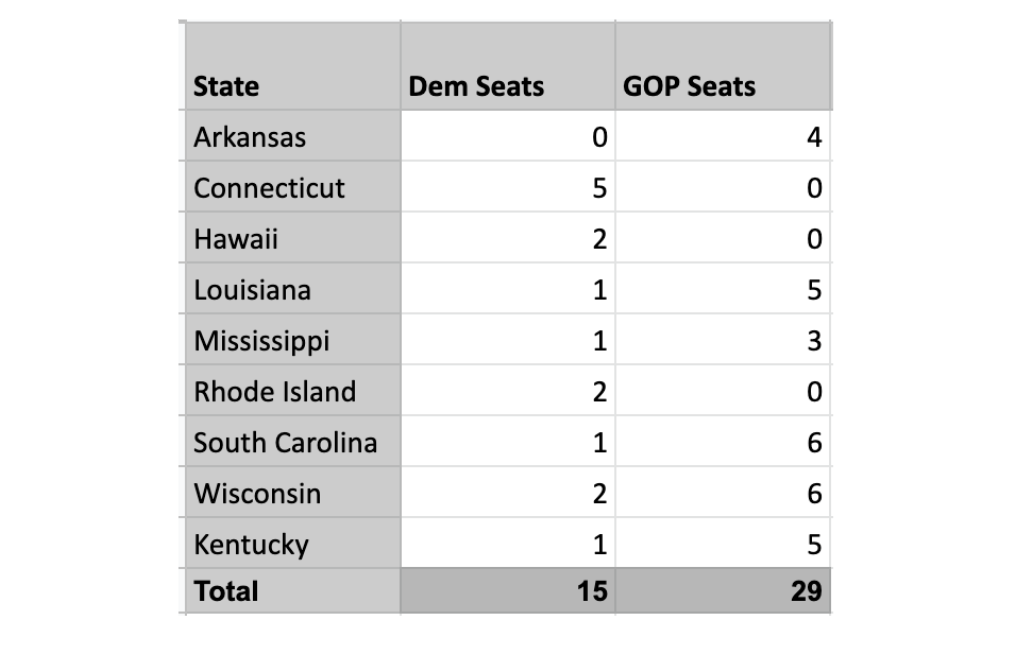

Moreover, in many other states — think Arkansas, Idaho, Mississippi, Louisiana — it’s nearly impossible for Republicans to turn their legislative control into additional seats beyond what was already in place. In a small way, the same factors that advantage Republicans in the Senate make it harder to convert control into additional House seats.

Democrats' use of non-political commissions as a reform probably has hurt them in the redistricting fight. California could easily be made a 50-2 state with partisan redistricting and Colorado could have been made 6-2. And Democrats have likely made themselves more vulnerable to losing a substantial number of seats in even a mild red wave: Those three Nevada seats discussed above could all be lost. In New Mexico, Democrats could lose a seat that is currently safe. These maps have also made a blue wave less likely to turn into large majorities, with Republicans building their walls higher in states like Texas, locking in a number of seats with harsh conditions.

But Democrats have rightly made the calculation that the goal is to get to 218 seats and to control a majority. Their redistricting decisions make that goal more plausible in a 50-50 election year. Perhaps they lose the House in 2022 as in-power parties typically do in midterms. In 2024, however, Democrats may be able to avoid the fate that Democrats faced in 2012, when they won a majority of the national popular vote but still lost the House.

* This analysis assumes that no Federal court will reject a map absent an abject violation of the Voting Rights Act, but state courts can reject maps on their own terms.